Bybee Family History & Genealogy

Bybee Last Name History & Origin

AddHistory

We don't have any information on the history of the Bybee name. Have information to share?

Name Origin

We don't have any information on the origins of the Bybee name. Have information to share?

Spellings & Pronunciations

We don't have any alternate spellings or pronunciation information on the Bybee name. Have information to share?

Nationality & Ethnicity

We don't have any information on the nationality / ethnicity of the Bybee name. Have information to share?

Famous People named Bybee

Are there famous people from the Bybee family? Share their story.

Early Bybees

These are the earliest records we have of the Bybee family.

Bybee Family Photos

Discover Bybee family photos shared by the community. These photos contain people and places related to the Bybee last name.

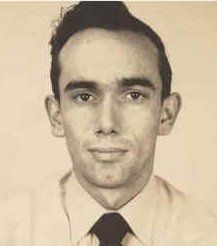

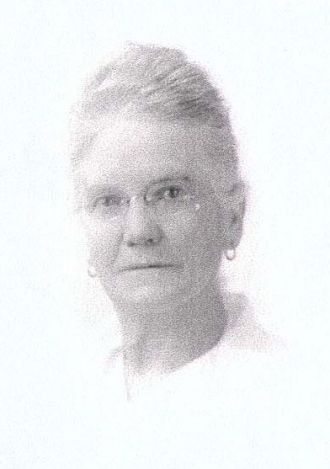

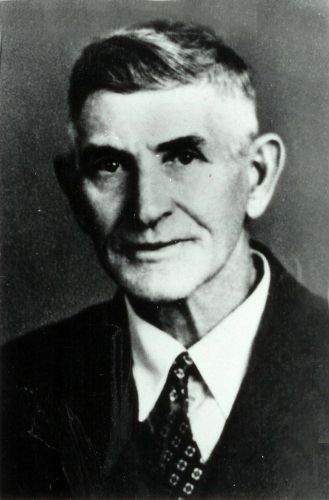

People in photo include: John William Bybee

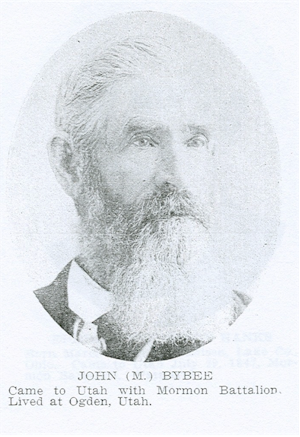

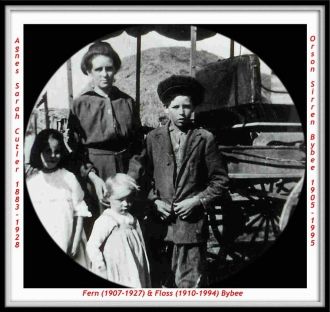

People in photo include: Levi Homer Bybee

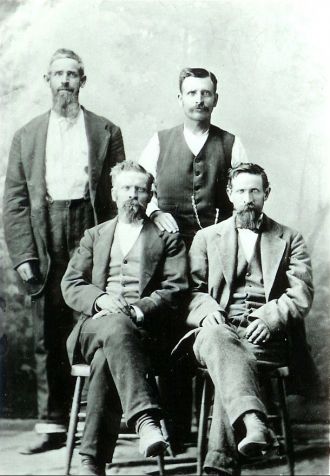

People in photo include: Polly Chapman Bybee

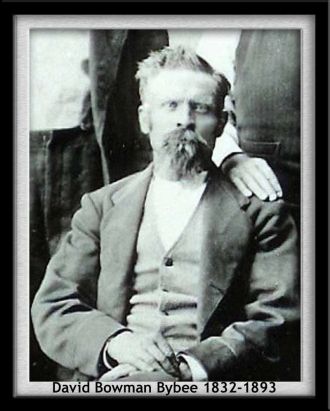

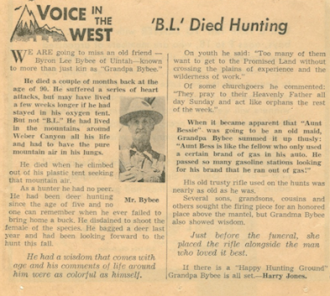

People in photo include: David Bowman Bybee

People in photo include: Lucinda Beckstead, George Bybee, and Lydia Bybee

Bybee Family Tree

Discover the most common names, oldest records and life expectancy of people with the last name Bybee.

Updated Bybee Biographies

Popular Bybee Biographies

Bybee Death Records & Life Expectancy

The average age of a Bybee family member is 73.0 years old according to our database of 1,550 people with the last name Bybee that have a birth and death date listed.

Life Expectancy

Oldest Bybees

These are the longest-lived members of the Bybee family on AncientFaces.

Other Bybee Records

Share memories about your Bybee family

Leave comments and ask questions related to the Bybee family.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It was through the dedication and commitment of Lee J. Bybee, a grandson of R. L. Bybee, that the continuation of this good man's history was promoted.

A special thanks to Clendon and Jay Bybee, Ray Bybee's sons, for making available the larger part of the personally written history of Robert Lee Bybee.

To complete this personal history of Robert Lee Bybee, careful and extensive research has been made. This research includes written records of factual events and dates of his life's history. The greater part of this history was written by Robert Lee Bybee. Other sources include: "History of Menan, Idaho;" " History of Milo, Idaho;" "History of Iona, Idaho;" and "Progressive Men of Idaho."

Most of these sources have been made available through the libraries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. The correct dates and many significant details of L.D.S. Ward histories have been carefully documented.

Other reliable sources are authentic stories and histories of some of R. L. Bybee's grandchildren who are still living (1989). Grandchildren who willingly shared histories, stories, and events as they remembered them of this greatly loved and respected Grandparent, Robert Lee Bybee, are Clendon Bybee and Jay Bybee, (sons of Ray Bybee); and Guinevere Hancey, Denzil Hancey, Wanda Christensen, and Donna Hillman, (son and daughters of Minnie Bybee Hancey.)

Events written by family members are true, however, dates are not certain. So the word "approximate" will appear. All writing submitted I believe to be "reasonably" correct.

So through records, histories, and family writings, I have been able to write and adapt to what I hope is a convincing conclusion to a "labor of love." For without everyone's efforts, I could never have successfully accomplished it. I respectfully present this work for publishing realizing there is yet much that could have been written had the correct information been available.

Signed, Donna Hillman (Daughter of Minnie Bybee Hancey) 1989

In preparing this published history of Robert Lee Bybee, we have not changed the original typed manuscript. We have, however, divided paragraphs and added punctuation to add clarity. We have left misspelled words as we found them when it appeared not to be a typographical error and have enclosed them in accent marks. The many hours spent in typing and editing this history have brought Great Grandfather Bybee to life, and we feel we have come to know him. We appreciate the opportunity to be a part of this work.

Linda Kaye Hillman Shearer and Dale Shearer

I, Robert Lee Bybee, was born on the banks of the Eel River, in Clay County, Indiana, U.S.A., born May 4th, 1838, son of Byram Bybee and Betsy Lane.

I would say as the Prophet Nephi said, "I was born of goodly parents" and was taught in the ways of righteousness and learning as that day afforded.

The following incidents are a few of the events that have occurred in my life. For the first four years of my life my father was engaged in the pursuit of agriculture in the above county and state. As a matter of providing the necessities of life for the family, he also repaired shoes for those who required the service, and as occasion required he would construct the shoe "thruout."

When about four years of age my parents moved from the state of Indiana into the state of Illinois and settled in the city of Nauvoo.

At this point I would like to state that I am 87 years of age and offer these memoirs after an elapse of about 80 years, but to the best of my memory we lived in Nauvoo about one year, moving then from Nauvoo to a farm about two or three miles south of that city. The property to which we moved belonged to Daniel Smith who had married my sister Elizabeth. While living there I recall the following incident. As was the custom among the early pioneers, my mother was making soap in a large iron kettle which she kept for that purpose. While thus engaged five mobocrats came to our home and ordered my father with his family to leave immediately for Nauvoo. At their approach my mother was stirring the soap with a stick she had for that purpose. She shook the stick at the leader and said, "We will not leave here until my soap is done." At that they laughed among themselves, at the captain, and rode away. Next morning my father was standing in the door yard when we heard the report of a rifle, and a bullet whizzed over Father's head. We took this as a warning that we should leave as soon as possible, which we did, returning to Nauvoo after an absence of about one year.

I received my first schooling as a result of our return to Nauvoo. I was then in my sixth year, this being 1844. I remember well the school house as it stood near the bank of the Mississippi River, and the teacher's name was one Mr. Church. We lived west of the temple four or five blocks on the bank of the river.

The mobs at this time around Nauvoo were very bitter against the Saints, and their activities forced the people to leave their farms and other properties and flee to Nauvoo for safety. A man returned to his own property at the risk of his own life to harvest his corn or to get meat for his family.

I relate an incident here to show how the mobs were treating the people. When we decided to move back to Nauvoo, my sister Elizabeth and family decided to remain on their farm and harvest their crops. At this particular time Elizabeth"s husband was not at home due to the fact that the mobs were pursuing the men so closely that they were forced in hiding to protect their lives. Sometime during the fore part of this particular day four or five mobbers came to the house and told Elizabeth if she had any personal properties or valuables she wanted in particular to get them immediately as they had come there to burn their home. Among the things she removed from the house was a fine stone jar that belonged to my mother, and which she had brought with her from her home in Indiana. Elizabeth had the jar because Mother had no cows in Nauvoo and so had no use for the jar which was used for a churn. As she came out with the jar one of the mobbers said to her, "There is my mother's churn. You stole it from her." But Elizabeth replied, "You are a liar, my mother brought that churn from her home in Indiana," to which she received no reply.

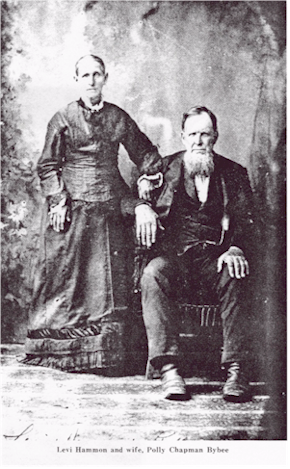

Before we left Indiana two of my sisters married. One of them, my oldest sister Polly Chapman Bybee, married Levi Hammon. The other sister following her in age, Rhoda Bybee, married David Bair. To the best of my recollection, Levi Hammon joined the Church and moved to Nauvoo in the spring of 1843. David Bair did not join the Church and did not move west, spending all his days in Ohio and my sister Rhoda with him.

When Levi Hammon came west to Nauvoo, he brought with him a team of horses and a wagon. One day Levi, Father, and myself, with my younger brother Byram who was three years younger than myself, went up to watch the work on the temple. As we were returning home in Hammon's wagon, we met an outfit of three or four mobbers, all armed, and they had my brother-in-law Daniel Smith prisoner. When we met them Levi Hammon stopped them, and Father spoke to Daniel, and one of the mobbers after an oath of profanity said, "Don't speak to him," and ordered the driver to drive on. Within a few days Daniel returned to Nauvoo having in some manner secured his release. We never knew how he gained his freedom.

We lived during the winter of 1843-44 suffering much for the want of provisions. Corn could be purchased in the market in Nauvoo for 10 cents per bushel, the problem being to secure the ten cents. I remember one day, my father who was somewhat of a sickly nature, very seldom doing any hard work, secured 10 cents just how I do not know, perhaps for repairing someone's shoes, a trade he sometimes followed and at which he was good for the day and age. He was honest in every respect, and his work was of the highest quality. The 10 cents that Father had he spent for a bushel of corn a part of which Mother used to make hominy. Father took the rest of the corn down to a grist mill down the river from our place to have it ground. The mill was owned by one Mr. Micksell. Father and Mr. Micksell were great friends. He left the corn at the mill with the request that it be ground as soon as possible and to which Mr. Micksell agreed. We were in need of the grist very badly at home as we had neither bread or flour in the house. Never can I recall while we lived in Nauvoo of having flour in our home. We considered ourselves indeed lucky to have corn meal, and there were times when we did not have that. The only flour that we ever enjoyed was given to us by a Nauvoo merchant named David Yearsley who lived near us. He was a splendid man and was surely a friend to us. Sometimes his wife would bring us a pan of flour or a plate of biscuits, and we would enjoy one of the rare treats of that time. The fact that the corn meal was so badly needed at home forced Father to see Mr. Micksell again about the grist but was told that it was not ready. After securing a promise that the grist would be ready as soon as possible Father returned home. Another visit followed the next day with the same result. The meal was needed very much at home so Father returned for the third time, somewhat out of patience, and reminded Mr. Micksell that this was his third trip. Mr. Micksell agreed with him and told him to come once more and that would be the fourth. So Father, returning the next day for the fourth time, got the meal.

During the winter 1843-44 our family consisted of the following children: Louan, John, Lucene, David, Byram, and myself. One morning in the early spring of 1844 Father called the family to his side and said, "Children, there isn't a bite of bread in this house and nothing to make it of. If you want to go up and work on the temple this morning, alright. I am not asking you too, but if you do I will try and have bread for your dinner." John and David were then working on the temple, and Byram and I spent most of our time up there helping to do what we could. We all went to the temple and worked that forenoon, and upon our return home, we found a corn-dodger which we certainly enjoyed.

In the early summer of this year, 1844, an incident occurred in my young life that marked itself very clearly in my mind, making an impression that is as clear today in my mind as it was then. I feel that it had much to do with the confidence I learned to place in the life of the Prophet Joseph Smith. The Prophet was a military man in no small degree, and it was an interest that he displayed along this line toward the youths of Nauvoo that prompted him to ask the parents of the community to allow their sons to subject themselves to the conditions and discipline of military training. It was during one of the sermons he preached appealing for the support of the parents and their sons in regard to this military training that he said, in effect, if they would allow their sons to come to him and subject themselves to military training and discipline, he could promise that they would never be killed by the bullet of an enemy.

In our own family this was readily accepted, and as a result, I received some of the early impressions that have remained with me "thruout" my life and are as clearly impressed on my mind now as they were then, being more clearly outlined than some things of much more importance seemingly.

There were only two members of our family whose age would allow them to participate in the organization. There were to be two companies each representing a different age. My brother David, some six years older than myself, [and I] were the two of our family. I can remember very distinctly the uniforms that were used. They consisted of practically anything that would keep us covered up. The only thing essential in the line of a uniform was the cap. It consisted of two strips of pasteboard fastened and so arranged as to slip over the head, with blue yarn tassels one on either end and one on top. The difference in the uniforms of the two companies was the red trimmings of the caps of the older company. I regret even now that I haven't that little old paste board cap to treasure, not only as a remembrance but as a reality as well. I remember very well the fate of that cap. My mother's impression of that cap was much the same as mine for when we left Nauvoo that cap was one of the treasured possessions lying in the bottom of Mother's wooden chest.

I was about 16 or 17 years of age, and we were living in Uintah, Utah, where I was prevailed upon by Malan Chase, a neighbor of ours, who had aspirations toward the stage, and who always wanted the cap and felt much surer of success when he had it on, to trade it to him for an old slate. A good slate in those days was considered quite a valuable piece of property, there being no tablets or blackboards for use in the home or in the schools.

Myself and my younger brother Byram spent much of the time during this period watching the progress of the men working on the temple raising the large stone to their places on the high wall of the building with the crude implements at their command. The process, though somewhat slow and inefficient, employed the block and tackle system. I can see very plainly in my mind the men as they prepared to hoist a stone to its place. They always sang the following song:

Rolling, a bolling and the ship is rolling,

Oh! Ho! Ho!

Rolling , a bolling and the ship is a rolling,

Oh! Ho! HO!

And following the last "Ho" they united their efforts and up went the stone.

Our other form of amusement that we enjoyed very much was watching the progress of the steamboats in the Mississippi River. Some little distance below our home in Nauvoo there was quite a rapid in the river caused by a projection of rock, and above these the larger vessels could not go. There were some "side-wheelers," a boat built with its power wheels on either side, that could pass over the rapids. There were also some stern wheel boats. I think one or two of them were able to pass over the rapids, and one, the "Warsaw," we were always particularly interested in because it not only carried the mail from Nauvoo up or down the river, but it always seemed to appeal to us with the ease with which it came or went. We, too, were perhaps more particularly interested in the "Warsaw" because it's name always reminded us of a community by that name whose people were embittered against the Saints.

There was very little work in Nauvoo that winter. The work on the temple was all donated. Aside from this there was a Cooper Institution, its purpose being to make barrels and kegs for the transportation of whiskeys, etc. There was some employment offered by this company in securing "hoop-poles" which were made from a slender growth of hickory, perhaps in their second season and very tough and pliable, and which were used very successfully for the purpose.

It was during the late spring and early summer of this year, 1844, that the mob actions of our enemies made it necessary for us to look to the future for a new place to live. Their depredations increased, and there was a constant flow of the Saints to Nauvoo. I remember the preparations of my folks to move westward to the Rocky Mountains for the whole Church was planning to go there. Previous to this time, as early as 1843, possibly 1842, there was discussion among the Saints of a move westward.

During this time and as far back as 1839, there seemed to a determined effort on the part of the mobbers to have the life of the Prophet Joseph Smith. For a period following the issuance of the Exterminating Order by Governor Boggs of Missouri, and after the Saints had moved to Illinois, the Prophet Joseph was allowed his freedom almost undisturbed, and during this time in the years of 1842 and 1843, I have seen the Prophet Joseph many times. I remember very distinctly having heard the Prophet preaching and teaching the people on Sundays in the beautiful grove in the eastern part of the city of Nauvoo, where the summer meetings of the Saints were held, and where we were nearly always on Sundays. My mother was a good church goer, and she always took the family with here. Perhaps the clearest and most impressive of my boyhood memories of the Prophet are the ones I recall of parades and drills of the Nauvoo Legion which made up the militia of Hancock County. I can see now the beautiful bay horse upon which he was always seated when in command of the Legion, and the figure he presented in the uniform he wore, which was as clean as a new pin and as neat as he could possibly be. I remember, too, seeing him frequently when he would pay our company a visit while we were in training.

The Prophet always spoke to us urging us to be good, clean boys. The last time I remember distinctly having seen the Prophet alive was in one of the parades of the Legion.

I remember very well the excitement prevailing among the Saints when the report of the Prophet's assassination reached Nauvoo. I saw the bodies of both the Prophet and his brother Hyrum after they were brought to Nauvoo. My mother took us boys to see them, father being unable to go on account of ill health, and both my sisters were away from home at the time. So I can say that I have seen the Prophet and his brother Hyrum both in life and death, and that is something that very few men living today can say.

It seems to me now that the remaining months of the year 1844, and until the early spring of 1845, my life was somewhat uneventful, there being nothing particularly worthy of note, unless it was the fact that during this time we labored under a false impression in regard to the preparations that were necessary for our trip west later. The idea was generally accepted that there was a scarcity of fuel for fires over the plains, and as a result we were cautioned to prepare as much food as we could before we started on the trip. Thus, the corn that we did not need for our daily use, we parched to be used later when we moved west.

This information concerning the scarcity of fuel for fire was in error, as we were later to find out, and as a result the practice of parching corn was discontinued early in the year of 1845. It was found that buffalo excrement, or "buffalo chips" as it was more familiarly known, could be used to very good advantage for fuel and were very plentiful, there being an abundance to be had nearly everywhere on the plains.

If I remember correctly, the first move of our migration was made about this time. It is true there was no movement among the Saints westward, but everyone seemed to be figuring on a move in that direction eventually. Circumstances I suppose had something to do with the move also. Nevertheless, when we crossed the Mississippi River in the month of May of this year, we always considered it the first of the moves we were to make with the Rocky Mountains as our eventual goal.

I remember very distinctly that the leaves were out on the trees, and the spring flowers were just coming out in bloom, and the birds were returning from the South, and their cheerful songs rang merrily out "thru" the woods.

Finally when all our preparations were completed, the family was all assembled on the east bank of the Mississippi waiting our turn for the ferry boat, which I remember well was a large flat-bottomed boat large enough to accommodate two teams and wagons at the same time. The boat was a very sturdy affair and was so constructed to make it practically impossible to sink or tip them over. They were operated entirely free of cables, the power being furnished by man, which consisted of one, two, or three sets of oars, as the case happened to be, arranged on either side of the boat, the size and character of which determined the number of sets of oars used, usually one man for each oar. The boat was guided by a man at the helm of the boat using the rudder.

At this point the river was practically one mile wide, and the current of the stream made it necessary to tow the boat a considerable distance up the stream in order to effect the proper landing on the opposite side of the river.

I wish here to make a note of the fact that Levi Hammon had also made preparations to move westward with us. He had joined us previously in Nauvoo in the year 1843, also joining the Church the same year as a result of missionary work of my father. The combined properties of the two families were insufficient to make the second trip across the river necessary, so we were both loaded on the boat at the same time. Our trip across the river was made without mishap, and we landed at Montrose, Iowa, almost directly opposite Nauvoo. (?) At this point the river forms the boundary between the present state of Illinois and Iowa. Our move westward was, as before noted, somewhat in advance of the Saints in general, this because of the foresight of my father in anticipation of the trouble the mobbers were later to cause the Saints. Father often remarked about the cloudy future of the Saints and seemed to sense the fact that trouble was in store for the Saints.

Previous to our move across the river, my father had made arrangements with a certain Dr. Todd to move upon a large tract of land he owned in Iowa, not far from Montrose. Dr. Todd wanted the land fenced. The kind of fence he wanted made was known as the "worm-fence." The rails and other materials for the fence were to be from the trees on the place. And it was with the intention of doing this work that we settled on the place. Father and Levi Hammon had contracted the work together so that we made the trip to the property from Montrose together and made our home together such as it was.

We did not have a house to move into so things were arranged as best we could which was indeed a very crude affair. There were many things that served to make things hard for us, and the presence of snakes and insects made it impossible to sleep on the ground. So we cut sticks long enough to stand above the ground about three feet after they had been driven in the ground far enough to be quite solid, and arranged cross sticks on these so that we could place the wagon boxes on these and which formed our sleeping conveniences. Levi and his family lived near us in a tent protected as well as possible.

There never was a time in Father's life that I can recall when he could do any strenuous work, and as a result the burden of our share of the work fell on the shoulders of John and David. John was then in his seventeenth year and David was fifteen.

Dr. Todd furnished our axes, a crosscut saw, and two or three iron wedges. The wooden wedges or gluts we made ourselves. The rails to be used in the fence were to be twelve feet long and were to be made of the easiest obtainable wood. The boys always preferred walnut because it split easily and the grain of the wood made it possible to make a nice uniform rail. David was a splendid worker, and his job in particular was to start splitting the logs that had been sawed into lengths by John and Levi. There is much more to splitting a log properly than is generally supposed. First the iron wedges are started in the ends of the log, one near the center above the heart, and the other one the same distance below the heart. The distance between the wedges was governed by the size of the log. The wedges were driven by being hit alternately with a maul. After the log started to split, the gluts were used if necessary to split them clear to the end. The portions were then quartered and split as many times as possible leaving the rail about four inches square. The piece of land we were fencing was only a portion of the whole property and was about one-half mile square, so that we had about two miles of fence to build. The rails were distributed by loading them on Levi's wagon to the places where they were to be used. Our supplies, particularly corn and pork, were furnished by Dr. Todd as part pay for our work. I don't know the particulars of the contract drawn up between them but when we finally finished the fence, sometime about the first of September, in addition to paying for our summer supplies, Father left there with a good wagon and a good yoke of young cattle.

Dr. Todd was certainly a fine friend of our family, and I believe Father could have made his home with him there if he had so desired. But Father's aims and desires were to go west with the Saints, and nothing was permitted to interfere with the plans. During the few months we spent on Mr. Todd's place, Byram and I were allowed almost perfect freedom to roam the woods as we pleased. We had no responsibilities except occasionally carrying water from a nearby spring for Mother. Usually we came when we pleased and went the same way.

When Byram and I were alone, we loved to hunt the nest of the quail, and this was possibly our greatest pastime. It not only afforded us great fun, but the eggs could be used by Mother in her cooking. There were times too, when we were allowed to go with Father into the woods to hunt squirrels. There were a great many of them in the woods around us. They were principally of two kinds, the gray and the fox squirrel, and either were very fine meat.

Father was certainly a very fine marksman. He owned a small calibre Kentucky rifle and prided himself in the fact that he could use it perhaps as well as any Kentuckian. Many times have I seen him spy a squirrel high up in the small branches of a tree and deliberately raise his rifle, and after a careful aim, fire, and down would come the squirrel, and very seldom would the meat be shot up very bad.

The squirrel meant more to our family than simply meat, for my mother was unfortunate in having very poor feet and only leather of the very softest kind could be used. The squirrel pelt when properly tanned made good, tough, endurable leather, and her shoes were always made of them by Father.

First Father put the pelt of the squirrel in the ash hopper, which contained the ashes Mother used in making soap for family use. Care was taken to cover the pelt with three or four inches ash and also that the ashes were quite damp. Perhaps it would be well to explain the ash hopper and why we kept the ashes. There was no particular shape to the hopper except that it would hold the ashes and was as nearly as possible watertight. The lower end of the hopper was arranged with a slightly sloping bottom, and on the lower side was a trough. When the proper time came for soap making, ashes were the source of our lye to be used in the process. Sufficient water was put on the ashes, and as it came "thru"to the trough, it as saturated with good, strong lye, which we caught in a bucket.

The pelt after having been left in the ashes three or four days, or until it was possible to easily remove the hair, was then removed and "thoroly" washed and placed in some soft soap. After three or four days, it was again "thoroly" washed then worked by hand near a fire until it was perfectly dry. It was then very soft and pliable.

One day about this time something happened to me I have no good reason for forgetting. Mother had sent me to the spring for some water, and some other things there I had become far more interested in. After I had been gone about one-half hour, Father passed the spring on his way to the woods and noticed what I was doing, and after reminding me to hurry up and to tell Mother when I arrived at camp to punish me. Well I hurried with the water alright, but I "thot" maybe by some lapse of memory Father would forget the licking business, and Mother would never know I was supposed to have one. I got by fine and dandy until Father came home and almost the first thing he asked concerning the licking, I admitted I had failed to tell Mother, and he assumed the task. I was much better satisfied with this arrangement for I would rather have taken two whippings from Father than one from Mother, as she had a process that commanded respect and no efforts on her part were misdirected.

Another thing that happened in our lives that was worthy of note much more then than now was one of Mother's Johnny cakes. Very few times after we crossed the Mississippi into Iowa we were without cornmeal, and here to our supply of white flour increased. Mother was an expert on the well-known corn dodger. But the times when Johnny cakes were made every one sat up and took notice. The things used to make the cake and the dodgers were practically the same. But the method was quite different. The cornmeal, salt, and water were mixed as for the dodger, but the big secret happened when the cracklings, the portion left after the fat of the hog had been rendered, were added. Johnny cake days were certainly rare, rare days to us then. They usually happened during the winter holidays, and usually represented grand occasions, and were always out of the ordinary for us. I believe in my boyhood days I never enjoyed any bread and cake any better than these.

It was quite a little trick to cook these cakes as they were cooked differently than the dodgers. Our cooking implements were of the very simplest. The dodger being cooking in the Dutch Oven, but the Johnny cake, by another process, being cooked before the open fire. We had no dripping pans in which to cook it so our crude but very satisfactory way of cooking it was as follows: The first thing was a good, heavy, thick piece of oak board perhaps one and one-half inches thick and about 15 inches wide and 18 inches long. Smaller boards were fastened around the ends and sides forming a sort of a container for the cake. It was then placed close enough to the fire to cook properly. The cake having been spread evenly over the surface of the board and at a slight angle by the fire, so the heat, as nearly as possible, could be evenly distributed over the surface of the cake. When the top surface cooked, the cake was turned over and cooked on the other side.

Except for the fact that we were fulfilling an ambition of my father's life in moving Westward, it was with real regrets that we moved from Dr. Todd's place. We were planning our course as nearly straight west as possible but the course we finally pursued was slightly north of west.

We went from Dr. Todd's place to Daniel Smith's place somewhere in the vicinity of Kanesville, Iowa. Our progress was purposely slow, because along the route we traveled, we took all the work we could possibly secure in order to get as much money and property as we could, sometimes helping some settler harvest his crops or in fact doing anything we could get to do. I do not remember many of the incidents that happened along our trip to Kanesville, but we arrived there a mighty little in advance of winter. We were quite fortunate here in fact we could move into a vacant house somewhere quite close to Daniel Smith's. Daniel had moved westward from Nauvoo about one year ahead of us and had gone to the place near Kanesville some fifteen miles North of the town as fast as he could. He being a very good worker and with the help of some mighty good sons, when we joined them there, they were quite comfortable. I am not sure whether or not he owned the house we moved into. I am more inclined to believe it was a house left by some pioneer in his westward move. We enjoyed ourselves very much here that winter and were quite comfortable.

When Daniel first came to Kanesville he located on the first stream north of the town, then known as Little Pigeon. And some eight or ten miles farther north was Big Pigeon. He located in this community particularly on account of the supply of wild game, making it possible to easily secure meat. There too was many wild bees. I remember the supply of wild honey he had on hand when we arrived totaling perhaps many gallons.

I would like at this point to make a few observations with reference to the industrial situation of the country. Quoting from "The Founding of Utah," by Levi Edgar Young, we find, "This was the age of new American inventions, when the McCormick reaper, the plow, threshing-machine and the sewing machine were changing the entire industrial history of America. Illinois was the "centre" of or the life of this new type of farmer.---Always on the frontier, the Mormons had learned inventiveness and resourcefulness;---They had felled trees and reclaimed thousands of acres of land.---They had entered on that period of industrial and social life---and the church and school were the "centers" of social and religious activities." The "thot" that we were living in this wonderful time and doing our bit in the great program of affairs, and eventually to found the greatest commonwealth of all time, has been a source of no small degree of satisfaction to me and was so to my father- whose vision of the West was in keeping with the wonderful things that have happened.

We made a move from where we were located for the winter sometime in the early spring to the headwaters of Little Pigeon where there was a large beautiful spring. Here conditions were such that we could locate easily, and Father, with the help of Levi Hammon, Daniel Smith, and the boys, built a house. We arrived here early enough in the spring to plow and plant some four or five acres of ground to corn and garden. This was in the year 1846.

Levi Hammon, who had been continually with us since we left Nauvoo, did not move to the headwaters of the Little Pigeon with us but remained in the house near Daniel Smith where he had spent the winter.

After completion of our spring work, Levi Hammon with his family, and Father, and my brother David went down to Missouri with their wagons and teams to find work.

Our private home life during the time Father spent in Missouri was quite uneventful. We cared as best we could for the garden and corn. Byram and I were permitted to about as we pleased most of the time.

The parties who had gone down to MIssouri remained there during the winter 1846-1847.

We moved from our home on the Little Pigeon down the creek to a house about one half-mile down the creek from Daniel Smith's home, which proved to be our farewell to the place. The move from our home up there was made after we had harvested all our crops and were quite well prepared for the winter. The move was made due to the fact that while Robert Lane, my cousin, and I were down in the corn patch we discovered the trail of an Indian who evidently was prowling around the place. Mother was somewhat prepared for the news of our discovery for she had heard him during the night and had said nothing about it.

The Indians in that country were known as the Omahas, and while they were not particularly unfriendly, they would steal anything that was loose. Perhaps if he had appeared in the daytime we would not have been unduly excited, but things the way they were, we decided we had better move to a place nearer our neighbors, of whom Daniel smith was the closest, approximately five miles away. About a quarter of a mile about our new home, located on the banks of the creek, was a log house used for the purpose of meetings, dances, and socials. The music for these entertainments was usually furnished by Daniel Smith who was a first class fiddler if not a violinist.

For five days of each week school was held in this same log house. I never did attend this school although I was in my eighth year. The main reason I didn't attend was because I did not have a pair of shoes. Whenever I went outside, I had to wrap my feet in some rags or borrow someone else's, and other clothing was not very plentiful.

Perhaps the most cherished piece of property that we owned at this time was a cow which we had purchased or which was given to us by someone. I cannot recall just how we came to have the cow, but after we moved down near Daniel's, we would have had a serious problem in feeding her if it had not been for the kindness of Daniel, who allowed us to gather fodder from his patch. The fodder we used was located on the opposite side of the creek and about a half mile down it.

The creek at this place was four or five feet and comparatively narrow. At a point a little below the house, a bridge had been constructed that we used to cross when after fodder. Perhaps the main reason I remember that bridge so well is associated with Mother and her old stone jar mentioned once before. The depth of the creek under the bridge had much to do with my remembrance of it so clearly, but at one time during the spring, a freshet of more than unusual size followed a rain storm and rushed down upon Mother's milk house, which had been dug in the east bank of the creek under the bridge. The milk house was entirely destroyed. Mother was certainly disappointed for she lost everything in the cellar and felt especially bad because her pet stone jar was gone. However three or four days later the jar was recovered by Robert Lane, and his importance in our family was increased very much, especially with Mother. The jar was not hurt in the least.

It was during the winter spent here on Little Pigeon that something happened I want to relate here. No pioneer home of that date was complete without a few chickens, and they presented a serious problem on account of the great number of animals that were around always looking for a nice fat hen. We had our troubles with a certain red fox who insisted on getting Mother's chickens. His visits were frequent enough to demand some immediate action, so Mother told Robert Lane if he would catch or get rid of that fox someway, she would give him a chicken dinner, as she would rather give him one than give the fox so many. Robert set out to get the fox in a businesslike way asking Mother to furnish only a small piece of boiled meat. His plan was well laid, and before we retired the first night we had promises of success.

Three logs were placed close together, the middle one raised, and a figure four placed beneath the outer end, with the long or bait end back between the outer logs, and the bait of boiled meat placed on it with the hope that the fox would take the chance, which he did. I think there was about one foot of snow on the ground at the time. Sometime in the forepart of the evening we heard the log fall, and there to our joy we found Mr. Fox dead beneath the log. The pelt was removed from the carcass and cured as best we could do it.

Sometime before the pelt was sold, I was promised a book which was to be purchased from the money it brought. When the pelt was finally sold it was taken by to Kanesville by Daniel Smith, and upon his return home he brought me a book named "Parker's Second Reader," and I was as proud of that book as anyone could have possibly been. So that was the first book that I ever owned. I hadn't had that book very many months until I had memorized every thing in it. Some of them I can recall now and some of them express beautiful thoughts such as the following:

A little bird one day in June,

'Neath my window sang a tune,

Sweet and simple was the song,

It repeated all day long,

Then a while it went away,

But he came another day.

And with him a little mate he brought,

And to her his song he taught, chip, chip.

Now they two did build a nest,

And they seemed both double blest.

And whilst other birds had they,

And they, pretty things would say, chip, chip.

But a naughty puss one night,

Killed the young birds outright,

And their parents mourned the day,

Sat and sighed and went away.

Here's another,

A little mouse once had a house,

'Twas made of sticks and grass,

Quite happy here from year to year,

Her time did daily pass.

One summer day for work or play,

The mouse did leave her nest.

The young ones three, snug as a flee

Were gently put to rest.

But now a boy with thoughtless joy,

Did find the little mice

And in his hat, to an old cat

He bore them in a trice.

The poor old mouse came to her house,

When all her work was done,

And much distressed she found her nest

But all her young ones gone.

Here's one,

Caw! Caw! cried the crow,

I should very much like to know,

What thief stole away,

A bird's nest to-day.

The Robin,

To-whit, To-whit, To-whee,

Will you listen to me,

Who stole four eggs I laid,

And the nice nest I made?

The Cow,

Not I said the cow,

Moo! Moo! I gave a wisp of hay

But the nest I did not take away.

The Dog,

Not I said the dog, Bow! Wow!

I would not be so mean I vow,

I gave the hair the nest to make,

But the nest I did not take.

The sheep

Not I said the sheep, Oh! no!

I would not treat a poor bird so,

I gave the wool the nest to line,

But the nest was none of mine.

The Boy,

A little boy hung down his head,

And went and hid behind the bed,

For he felt so full of shame,

He did not like to tell his name,

For he stole the little nest,

From the pretty yellow breast.

Another.

Oh! Have you seen my nestlings dear,

A mother robin cried.

I cannot, cannot find them

Though I sought them far and wide,

I left them well this morning

When I left to seek them food.

But I found upon returning

I'd a nest without a brood.

(There was more to this one but I cannot now remember them. I can remember a few lines of many other of the little pieces but none entirely.)

During this summer, 1846, trouble arose between the United States and Mexico which resulted in war being declared. There had been a few skirmishes fought in Texas. There was a large tract of land in the West that belonged to Mexico that the U.S. wanted. It embraced several of the present states of the Rocky Mountain region.

About this time the Saints were seeking aid from President Polk in their journey toward the West. Even though the Saints were never afforded the protection they were entitled to, they were not in the least bitter toward the government. The plan of the Saints at Washington was to aid the government in holding the western country for the U.S., to repay for any help that was given them.

In the month of June, 1846, an officer of the U.S. Army came to Iowa. He had been sent there by the government to recruit 500 men from among the Mormons to help out in the trouble with Mexico. This was entirely a new and unexpected condition. Instead of receiving aid, the Saints were to lend aid.

Among some of the Saints this news was received with some misgivings, thinking that it was a conspiracy to destroy them entirely. They never had received any protection from the government, and they had learned to expect anything. However there was no question in the mind of President Young, and he offered the men and promised to have them as soon as they could be recruited. He figured that it was a test of the loyalty of the Saints to the country. The Battalion was organized at Council Bluffs, the Church Authorities lending all the aid possible in the recruiting. The entire Battalion was completely arranged and organized in three days. The following from the "Founding of Utah" by Levi Edgar Young presents a vivid picture of some of the sacrifices that were made.

"Imagine the feeling of the pioneers when they received word that the fathers and sons must enlist to go to war! The mothers of the young wept to think of the sacrifice; the young wives were brokenhearted. Yet they did not say a word nor do a thing to discourage the men. In fact, the women were willing that the men should give all for their country, and they determined to place their faith in God and suffer and be strong. It was a time of bitter trial as it was to the Saints, and when the time for parting came, the sorrow at leaving their families was almost more than the men could stand. The soldiers were poorly clad; and could they have foreseen the long journey over desert wastes and mountain passes, we sometimes wonder if they could have met their trials. But their courage was equal to the task before them, and the men set out unafraid."

Sometime during the month of June the word reached us concerning the Battalion. My brother John, who was then in his 18th year, (1847), made preparations to join the ranks, even against the wishes of Mother and the fact that Father was away from us. His departure was certainly a sad affair for us especially for Mother, and I'll never forget it as long as I live.

One Sunday while we were still living on the Little Pigeon something happened that I recall for two reasons. The first reason I remember it so well is on account of the consequences, and the other one is on account of the humor of the thing. Mother had the family to church, as was her custom, which was held in the little old log house. Byram and I were sitting together. He was amusing himself by running his fingers 'thru' my hair. It was fine with me for a while until he became too enthusiastic, at the same time I had gone far enough. Just then he caught sight of something in my hair, by this time he was very interested, and when I moved still farther out of his reach he called aloud in church, "Hold still Rob, it is a louse," which I suppose added some interest to the occasion.

Late in the spring of 1847 we moved again to a house located nearer to Daniel Smith's home. We were more or less dependent on him during Father's absence, and he sure was good to us. It was some time during the fall of this year, possibly in October, that Father returned from Missouri.

Father brought back with him a good supply of things, clothing and provisions, for our winters use. He also had an additional team of oxen. About September of this year my brother John returned to us from San Diego, California, where the Mormon Battalion had been disbanded. Unfortunately during this winter Father's health was very poor. This being the winter of 1847-1848.

After the assassination of the Prophet Joseph Smith, and Brigham Young had been chosen the leader of the Church, 1844, active preparations were carried on in anticipation of the great westward migration of the Church. We were somewhat out of communication with the main body of Saints, but we heard often of them and kept in touch with them as best we could. All the experiences of the Saints led them to believe that in the near future they would have to seek a new place to establish their homes and other institutions that mean so much to the Saints.

Nauvoo was practically deserted in the year 1846. Nearly every home was occupied in making something to be used on the journey west, ranging from wagons on the outside to stockings on the inside.

The fortunes of the Saints varied 'considerable' during the winter of 1846-47 as they wended their way across the present state of Iowa, which at this time was a haunt of many Indian tribes. The whole territory was full of trails, but there were no roads, and the one that the Saints were to blaze was destined to be used for many years to come. The extreme cold of the winter caused much suffering. The Saints finally concentrated their efforts and formed Winter Quarters on the west bank of the Missouri River. This proved to be the point where all the companies to travel westward had their origination.

Father's life long ambition to go west with the Saints failed to materialize in the year of 1847 mainly for the reason of his ill health, but even after their departure, his desire to move west was always foremost in his thoughts.

The fortunes of the family, while they were improving from year to year, was the main reason why we did not make the trip. Father could not see how it was possible for him to undertake the journey with the equipment he had.

Our lives were quite uneventful during the winter of 1847-48.

(Page 18 had only the above line)

Heber C. Kimball at this time was one of the leading members of the Church and was a very good friend of Daniel Smith. He called Daniel his Nimrod. Heber C. Kimball at this time was making preparations for the move westward with the Church. Except for the fact he wanted two more yoke of oxen and a driver, he was ready to go. One day when Daniel was in Kanesville, Daniel chanced to meet Mr. Kimball, who during their talk mentioned his needs and asked Daniel if he could possibly help him out, but was told he couldn't but recommended Father, as he had the two yoke of oxen wanted. Father was home sick in bed at this time and Daniel so advised Mr. Kimball. He asked Daniel to return home and tell Father he wanted him to come to Kanesville and see him, this in view of the fact of Father's illness. Father very reluctantly made the trip on Daniel's favorite horse named Jim. He was prevailed upon by Mr. Kimball to agree to make the trip westward as far as the upper crossing of the Sweetwater River, somewhere in the present state of Wyoming, where the Old Mormon Trail leaves the Sweetwater to cross the Rocky Mountains. Father returned a few days later and immediately started making preparations for the trip. I believe he left us sometime in the month of May to join Mr. Kimball in Kanesville. Mr. Kimball was to meet a portion of his family in Winter Quarters, just across the Missouri River from Kanesville, which he did. They crossed over the river on a ferry boat about July 1, 1848. About the middle of September he returned to us from the Sweetwater trip, and I recall the stories of the many wonderful things he told of having seen on his trip, especially the ones relating to the countless number of buffalo that were roaming the country along the Old Mormon Trail. About this time they were just returning north from their winter range in the South, the buffalo being a migratory animal. They ranged as far north as the Dakotas of today. Another thing to greatly impress Father was seeing the tips of great high peaks of the Rocky Mountains above the level of the clouds.

I recall a little incident now which I think worthy of mentioning. It concerned a son of Mr. Palmer, known around the country as Pokey. He was about nine years old. Most of the crops had been planted, and the crows were causing much trouble, especially with the corn. They seemed to know corn time and could locate the hills of corn as readily as if they had planted them themselves. It was to prevent as much damage as possible that Mr. Palmer decided to give Pokey his chance to be of use and promised him, if his work were satisfactory, a new hat. Pokey's efforts were satisfactory alright for one day he was taken to St. Joseph to pick out his hat. Pokey's last few weeks had been nothing but crows, and it seems he was still thinking crows while in the store. Mr. Palmer was busy talking with someone, and Bill Boon, the clerk, approached Pokey, whose mouth was open as were his eyes. Boone joshed him a few minutes about the number of different things in the store. Pokey agreed he could see many things. Boone, a little proud of the stock, told Pokey if he could think of a single thing they didn't have he would give him a new hat. Pokey looked quickly around the store and asked if they had any crows, and as a result, later walked out with a new hat, and one his father didn't buy.

We spent the winter of 1849-50 on Mr. Palmer's place, and due to some trouble, the nature of which I cannot recall, we moved from the Palmer property to a place three miles farther on up the Missouri River belonging to a Mr. Henry Catlet. Levi Hammon also moved with us to the Catlet place. Here our work was about the same as it was on the Palmer place, except that we worked almost entirely with charcoal. We made this move sometime during April and thus were able to plant some corn and a garden. Another thing that Levi Hammon could do very well was construct wagons. He was a first-class wheelwright, and much he busied himself making wagons during much of the summer and fall spent on the Catlet place. Things had so arranged themselves that we were quite sure of getting away the following year for the West. Practically the very first necessity in an outfit for the trip was a very good wagon, because the dry, excessive heat of the desert, and the rough roads, and usage were extremely hard on wagons. Experiences of those who went ahead of us proved the necessity of a good wagon. At first Levi did not spend as much of his time working on them as he was forced to do later. He made two wagons, one for Father, and one for himself. By fall, he had them both made and during the Winter they were taken to St. Joseph to be ironed, which work was done by Mr. Litz. He took charcoal as payment for his work. All parts of these two wagons, except the iron parts, were made by Levi. The times when Levi was not working on the wagons, he was doing carpenter work with Mr. Litz in St. Joseph.

Here on the Catlet place, another of those "first time" affairs overtook me. Boys in those days were just as much boys as they are today, and as is usually the case, there are some things we have to find out for ourselves, and more so is this a fact if someone else's boy can successfully do something we have never tried to do. It is usually the last times that are sad times, but I've had fewer sadder times than this first time, which had to do with a "chaw of tobacker." Some near neighbor of ours, whose name I have entirely forgotten, had a boy named Jack who was my side-kick and pal of those days. I don't know how long Jack had been using "tobacker," but this day he seemed to me to be as proficient as anyone I had ever seen in the business. Jack spent as much of his time as he could with Byram and me, and the three of us were nearly always in the woods after wild berries, especially mulberries, raspberries, strawberries, and blackberries, which were very plentiful around our home. It was on one of these excursions that I noticed Jack occasionally stick his chin out and drop a little something from his mouth to the ground. I noticed the little spots on the ground and decided it was "tobacker". When I questioned him, he said it was and asked me if I didn't want to learn to chew. He agreed if I would learn to chew, he would furnish the "tobacker". All's well that ends well; however, in this case I never calculated on the end at all, and Jack never said a word about what was usually the result of the first chew, nor did he warn me about swallowing the juice. Well, Jack produced the plug, and I took a good hearty chew, afraid perhaps I wouldn't get another chance. I immediately went to work on the tobacco, and between the times I spit the juice out in the approved manner, I swallowed much of the juice. In fact, I supposed if I didn't want to spit out the juice, I was expected to swallow it. Everything didn't go lovely very long, for the trees started cutting up capers, and I couldn't navigate straight ahead, and I became so dizzy I couldn't walk. I called to the others that something was wrong, and when they came back, I decided I wanted a drink, and between the three of us I got a drink. But that was way short of curing all my ills, so we decided to hit out for home. Byram on one side and Jack on the other formed my main means of transportation, as I was growing more unconcerned every minute. Finally, we came upon David burning a pit of charcoal about 100 yards distance from the house, and here I fell to the ground, hoping for the best and that soon. As soon as David saw me, he called to Mother that I was poisoned, and she came to me as fast as she could. Meanwhile, Jack showed that he was a pretty bright boy for he slipped out for home; by this time Mother had found out the cause of my ailments, and but for Jack's foresight, she would have derided him first. That was one "first time" that has never been repeated in a single instance. As a result of this episode I had to stay in bed, and believe me I was sick for two weeks, I was literally poisoned.

Before Father left Heber C. Kimball at the upper crossing of the Sweetwater, they had an understanding about the time, as nearly as could be figured out, for the trip West. Mr. Kimball's advice to Father was to return to Kanesville and with the family move to Missouri, where he thought Father could easily outfit himself in about two years. As mentioned before, Father did move to Missouri. But before we had left Daniel Smith's place to go to Missouri, we had been joined by Father's Uncle, Lee Bybee, and his three sons, who were all married and had families of their own. Here also lived Alexander Beckstead, the father of Henry Beckstead, who had married Lucene. Uncle Lee's sons were named Alfred, Absolom, and Lee. This gathering of our people was made in anticipation of going West, our intention being to travel together. In some manner, when we left, these people gained the impression that we were going to return to them in 1850 to start out. We had not intended to agree to any particular time for the start, intending to go as soon as we were able. As we have noted before, we were planning on making our start in the spring of 1851, and it was with this intention of finding out if they would be ready, that Father and I started to go back to Kanesville to ascertain how near ready the folks there were. Father also had a little scheme to make some money on the trip. It was arranged at the proposal of Mr. Burns, a neighbor who lived near us, that we should take with us a supply of bacon he had on hand, agreeing to pay Father for his services. There was quite a bit of bacon, but it lacked `considerable' of being a load. It was figured that along the way to Kanesville we could easily sell the bacon, as there were great numbers of people then on the move west, not only Saints, but gold-seekers in their mad rush to California as well. We sold most of the bacon on the way up but reached Kanesville with a small supply.

One day when we were nearly to Kanesville, while traveling a piece of road that nearly paralleled the river altho some distance from it, Father noticed on the bank of the river quite a number of wagons. He thought this would be a good place to dispose of the balance of the bacon, so we turned off the road to their camp. Here we received a great surprise for this camp belonged to our people from Little Pigeon. They were ready to go west and were there waiting for us to come from Missouri. Our meeting was entirely accidental. It was, of course, out of the question for them now to wait for us, but the final decision was that they should go on without us, which they did. This was in accordance with their understanding that we were to start in 1850. John, sometime previous to this, had gone back to Kanesville to Daniel Smith. We found him at Kanesville intending to go west with them.

Father and I stayed long enough at Kanesville to see the folks all safely across the river and then started home. This trip was made during the month of June, our return to the folks on the Catlet place being about July first. At one of our camps on the way home, Father was approached by a stranger who evidently lived somewhere near, and asked if he would sell him a yoke of cattle. Father thought a few minutes and decided he would sell him the cattle for $35.00, which was agreed to. The reason I recall this so plainly was due to the fact that Father was paid the entire $35.00 in half-dollar pieces. Everything was okay when we got home, but much disappointment was felt because we were not to travel with the rest of the folks. Mother felt quite bad, for Elizabeth and Lucene and John had gone on, and conditions were so uncertain that she would liked to have had all the folks make the trip together.

About the time of our return, one of Mr. Catlet's slaves, a negro boy about sixteen years old named Dick, put on a little show that caused us much fun, even though it caused some pain for Dick. He was working in the corn one day with an old horse who knew just as well as Dick the meaning of the dinner bell, and it was necessary to show some speed if you even wanted to go to the barn with the horse. Dick unhooked the horse, climbed on and was off for the barn. Before entering the barn it was necessary to go through a corral. The entrance to the corral was through a set of bars. To Dick's hard luck, the top bar had been left in place. I guess he failed to notice the bar for he made no effort to get off the horse, who was now on a good big trot. He took the bar about midsection and entirely lost the horse. Catlet saw the whole affair and asked Dick why he hadn't got off or at least fell off, and Dick replied, "How the Debil could Ah fall off, when it was all Ah could do to hang on."

It was in September we burned our last coal pit. Levi was spending his entire time now on the wagons; Dave was working most of the time for Mr. Burns and the rest of us were doing only the minor things and caring for the stock. All our efforts were now toward getting everything ready for the start in the spring. We were getting hold of everything we could, and every penny in money was saved. Talk about saving and pinching, we were surely good at it, and it was a very good thing we did. I remember when we first moved on Mr. Catlet's place, we moved right among a small grove of sugar maple trees. We never could understand why, but these trees had never been tapped by Mr. Catlet or anyone else. Father asked about them and was given permission to tap the trees but to do them as little harm as possible. So during the month of March, 1851, we got all of the maple sugar and syrup we possibly could. March is by far the best month to tap the trees, so that when we left we had considerable sugar and several gallons of syrup. I recall the race we used to put up with Mr. Catlet's pigs in order to beat them to the sap that had dripped out during the night. Mother had practically given up her butter business as there were no teams traveling to town, and it was not worth while to go for the butter alone.

Every year at the approach of autumn, as had always been our custom, we made an effort to get as large a supply of nuts as possible for our own use. Many falls previous to this year, 1850, I recall the enjoyment and fun we had gathering nuts, and I can truly say that some of the most pleasant evenings of my boyhood were spent cracking them. The kinds we usually gathered were black walnuts, butternuts, hickory nuts, and hazelnuts. No winter was complete without nuts. Associated with these evenings of cracking nuts on the Catlet place, I recall a very large negro slave, belonging to one of our neighbors. His master was very kind and good to him, but he liked Father very much, and he spent as much of his time as he possibly could with us. Nearly every evening he was there to help with the nuts. Every time he saw Father he always wanted him to promise he would take him west with him. But Father told him he couldn't because he belonged to another man, and it would be stealing to take him. He then wanted Father to let him join us in Kanesville after he had run away, but Father wouldn't consent to that even, because the owner of the slave and Father were very good friends. After we left there we never saw him again.

While we were located here on Mr. Catlet's property and soon after we had moved there, one of Polly's little girls, about ten years old, became ill, and after a very short illness died and was buried there. I cannot recall her name or the cause of her death, altho it was some kind of fever.

Everything moved along smoothly for us, and the excitement among us increased as the day approached for the start. Some three or four days previous to the grand starting, all of us were assembled and taken to St. Joseph for our final view of the place, and to purchase our supplies for the trip. In looking back to the time of those preparations, I can see Father in one of his little stunts. The money we had saved was all put together in a meal bag whose capacity was about two bushels. In those days Mother made all our bags out of almost anything she could get that was stout enough. Of course the bag lacked quite a considerable of being full, but our fortune was all there. We had no paper money then, and with the exception of a few pieces of gold, everything in the bag was silver, the total amount being about $200.00. We had been advised by the authorities of the Church to bring a supply of flour with us large enough to last at least six months after our arrival in Salt Lake. For this reason we kept only enough of the money to meet the necessary expenses of ferrying and other incidentals. I remember Father as he sauntered in the Bedeford & Riddle Store on this morning carrying the sack containing the money over his right shoulder. He tossed the sack and its contents to the floor at the same time telling everyone present this was his last trip to St. Joseph for provisions, and it was. I remember very little about the prices of the goods there, except sugar, which was sold eighteen pounds for a dollar, and it was just ordinary brown sugar, as this was long before the day of granulated sugar. When our trading was finally completed, we returned to the Catlet place. The arranging of our load and completing all the details preparatory to our start occupied our last three or four days on the Catlet place. Finally the day for our departure arrived, and bright and early on a beautiful morning early in June, 1851, we took to the trail. Levi Hammon was about a week or ten days later leaving there than we were, owing to some uncompleted affairs between him and Mr. Litz. He was to join us at the ferry on the east side of the river at Winter Quarters. We proceeded very slowly, traveling short hours and taking things easily, and when we did arrive at the ferry, we had a very short time to wait for Levi. Immediately upon his arrival we made arrangements to cross the river on the ferry. We made the trip first; Levi followed immediately after us, and we went into camp in Winter Quarters for about a week while the arrangements were completed for the train with which we were to travel.

I wish here to say a little about the organization of this train, which consisted of one hundred wagons, and some of the conditions existing during our trip. First, there were two companies formed out of the one hundred wagons; that would be fifty wagons per company. These two companies were under the control of a captain, and their departure was so arranged and timed so as to be about two weeks apart. The reason for this two weeks span of time between the two companies was to prevent the occurrence of insufficient grass for the stock, the supply of which was somewhat regulated by the buffalo who often passed over the trail and left very little grass behind. There was a captain chosen over each fifty wagons, who was responsible for them to the man in charge of the train. Each company of fifty wagons was then subdivided into five companies of ten wagons each, and a captain was chosen for each of these companies. In each of these small companies of ten wagons, in order to prevent any dissatisfaction that might arise from choice of positions, the leading wagon each day dropped to the rear of the ten, and the same was true of the five companies; the leading company each day dropped to the rear of the entire company.

The man selected to be captain of the company which we were in and which was first to leave, was named Alfred Cordon. I cannot recall the name of the captain of our "ten." In every company of ten there was also one man appointed as hunter, whose duty it was to supply his company with meat. David was the hunter for our Company. It was also the duty of every able-bodied man in camp to take his turn doing guard duty at nights. When it was decided to make camp at night the leading wagon made a slight detour to the right in the form of a half circle. The twenty-sixth wagon in the line made a detour likewise, only to the left, thus forming a circle. Each wagon following its leader stopped with the left front wheel of his wagon close to the rear right wheel of the preceding wagon, thus forming a corral, into which our stock was placed at night, when it was thought necessary.

We broke camp at Winter Quarters and left there about July 1, 1851. Our trip was a very quiet one in comparison with some of those who had preceded us. Outside of the daily duties connected with traveling we had very little to cause us excitement. We had men always out on guard at night around the camp, as well as two or three men with the horses and cattle, so that when we spent our evenings around our camps, we felt quite secure and really enjoyed ourselves very much, singing, dancing, and rejoicing at the prospects of a brighter future.

Every company had its "fiddler" and evenings when all the work was done, we would find some nice, clear piece of ground as smooth as possible and have a dance. I never did any "fiddling" at these dances although later I became a "fiddler."

It always seemed to me that the real place to be in the train would be the leading wagon, and I awaited our turn with much anticipation. However, I was sadly disappointed, for the day we took our place to lead the train was by far the loneliest one on the entire trip from St. Joseph, West. There was no one ahead to see, no one on either side to talk to or play with, and I was surely glad when the day was over. Our company never tried to make a very large number of miles per day, it ranging from ten to fifteen miles per day. We never traveled on Sunday except in places where we had no feed for the cattle.

Before we left St. Joseph, Father sold all the young stock to Mr. Burns, our neighbor, as we were advised not to try to make the trip with them because they couldn't make the trip and would either be lost or form a burden to be cared for in the wagon, and every precaution was necessary to guard our teams, for on them depended our chance of getting to Salt Lake successfully. But Mother insisted on the cows so we had the six cows with us. I remember one day while we were stopped, eating our noon lunch, that Byram and I had a little "set to" about as follows: Mother was still protecting that old stone jar and was still making about as much butter as she could, at least we always had plenty. Her churning was done by placing the cream, when it was ready, in the jar and letting the motion of the wagon over the rough roads do the work. This was completed just about the time we were to eat, and it was during the meal when Byram and I had our misunderstanding. I cannot recall the issue between us, but I can very easily remember what Byram did. Picking out a moment when I was least prepared, he gave me his portion of the buttermilk, and it covered most of my outer clothes and wet me to the skin. I looked like a drowned rat, and the buttermilk made things that much worse. That created much fun in our company, and Byram and I have had many a good laugh over it since we became men.

I want to say something here about our "post offices" as we called them. They were a one-way affair in that the only information they furnished was to the company behind. Very frequently we found information of the company ahead of us. Nearly any place on the roadside we could find the old bleached bones of buffalo, and upon these were written our messages. The messages consisted of the date and enough information to let them know of our condition at that point. The bones, after the message was written on them, were placed in some conspicuous place by the road-side.

Occasionally as we traveled along we were forced to make unexpected stops on account of the buffalo. Buffalo, in their travels in search of food, always had a leader, and it was their custom to follow their leader if it was possible at all. Some of the earlier companies had made the serious mistake of trying to force their way through a herd of them and had found out that the buffalo would not give up their right of way but insisted on following their leader. Where it had been tried, the result was usually a stampede among the company's stock, as well as among the teams of oxen. So when we encountered them on our way, we stopped for them to go by. Now and then along the Platte River we were forced to wait for them to clear out of the river where they were drinking. Some of these waits sometimes lasted three or four hours.

If I can remember correctly, it was two or three days travel east of Fort Laramie that we passed a large column of rock extending into the air about 25 or 30 feet, then called "chimney Rock." It was on the south side of the river, perhaps two or three miles from the road, which was on the north bank. We were all quite curious about it when we passed, as we had been able to see it for several days before we passed it. It was possible to see it even after we had passed it for a considerable distance. It was the only rock formation near there and was quite a freak of nature to us.

Outside of our own train of people we saw only one white man from the time we left Winter Quarters until we reached Fort Laramie, and that was the man who ferried us over Loop's Fork. Here our cattle were forced to swim across the stream. We did not meet a single outfit nor did we pass any on that part of our trip.

On our approach to Ft. Laramie, we saw many Indians who had their tepees pitched near the fort. The majority of them were Sioux, and they were a mighty fine race of people, large in stature and as brave as any man ever was. There was no way to scare a Sioux.

In the route we were traveling, Ft. Laramie was just about one-half the distance to Salt Lake. We spent as little time as possible and were soon leaving the Fort for the rest of our journey. So well had our trip been planned before we started out that it was unnecessary for us to purchase any supplies at the Fort. It was, I think, about the middle of August when we left Ft. Laramie. We traveled out of Ft. Laramie up the North Platte River for about a week. We crossed the North Platte River again to the north bank about this time. As I remember it, the next water of any importance that we came to was the Sweetwater. Sometime during the time we were traveling between these two streams, we came to the place where the Old Oregon Trail left the Old Mormon Trail. Its general direction was northwest. The people of the company we were traveling with were not all Mormons. They had joined us to travel with us for protection and security until we came to the Old Oregon Trail, but here our ways separated, and some eight or ten of the wagons left us for the northwestern part of Oregon Territory. We traveled without incident until we reached the Sweetwater, where we arrived all okay in due time. It was by now well toward the latter part of August. We traveled up the Sweetwater River to the place where we were to gross over the Rocky Mountains called the South Pass. I remember one of the first natural wonders we came to. It was called the Devil's Gate and was on the Sweetwater River. In all the travels of the pioneers, the Devil's Gate was one conspicuous land mark. Many events were recalled and their scenes were brought back to memory by reference to the Devil's Gate. The water of the river ran through the Gate, which was approximately 100 feet in height. We were approaching the Rocky Mountains and were traveling nearly straight west, possibly bending a little to the north. The mountain which the Gate was found in was somewhat smaller than the main range and was a spur running out into the plains in an almost easterly direction. The walls of the Gate were almost perpendicular and were of solid rock. The next natural condition we observed was Alkali Lake. This was not only a matter of curiosity to us, but one of concern as well. The supply of water to this lake seemed to be independent of any stream, for as I remember it there were no streams running into it. Possibly the high water of the Sweetwater and local rains were the source of its supply. Occasionally during the warmer months of the year the water was entirely evaporated. The lake covered perhaps 25 or 30 acres of ground. Several days in advance of reaching the lake, we noticed indications of alkali all along the road. Practically all of the water of the country around the lake was more or less saturated with alkali, and this was particularly true of the lake itself. The excessive amount of alkali found through this country made it necessary to use precaution with the stock. Many cattle that had fared quite well thus far died of the effects of the water and the feed of this section. During the season of the year when the water was entirely evaporated from the lake, it was the custom of the early settlers to return to it to obtain the substance that formed on the surface of the lake, known to them as salaratus. This substance was used then among those early pioneers for the same purpose we now use soda. This salaratus could be picked up by cupping the two hands and scooping it up. Precaution was taken to keep it dry after it had been scooped up. Good wagon boxes were usually used, although smaller boxes could be used, according to the condition of the wagon box.