Camacho Family History & Genealogy

Camacho Last Name History & Origin

AddHistory

We don't have any information on the history of the Camacho name. Have information to share?

Name Origin

We don't have any information on the origins of the Camacho name. Have information to share?

Spellings & Pronunciations

We don't have any alternate spellings or pronunciation information on the Camacho name. Have information to share?

Nationality & Ethnicity

We don't have any information on the nationality / ethnicity of the Camacho name. Have information to share?

Famous People named Camacho

Are there famous people from the Camacho family? Share their story.

Early Camachos

These are the earliest records we have of the Camacho family.

Camacho Family Members

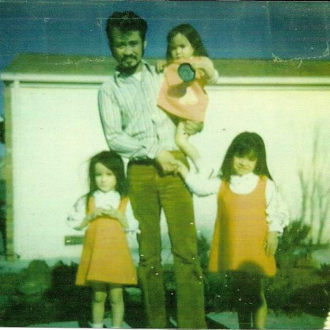

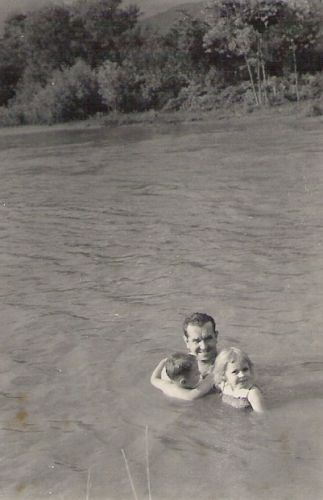

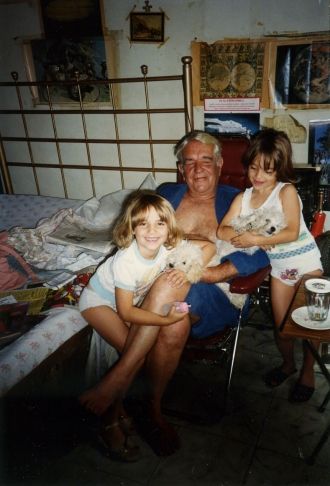

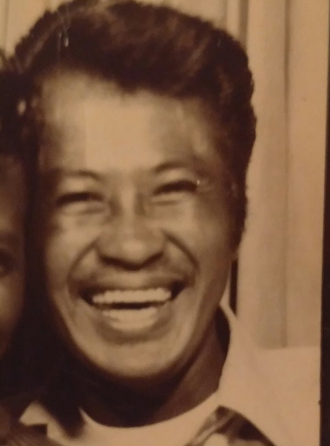

Camacho Family Photos

Discover Camacho family photos shared by the community. These photos contain people and places related to the Camacho last name.

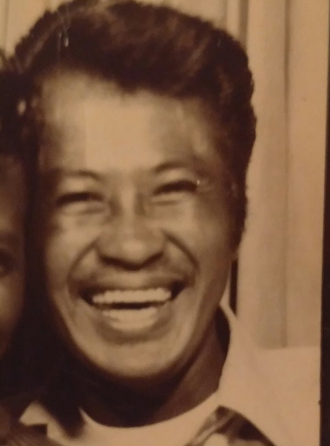

People in photo include: Francis Rita (Camacho) Albitre

Camacho Family Tree

Discover the most common names, oldest records and life expectancy of people with the last name Camacho.

Updated Camacho Biographies

Popular Camacho Biographies

Camacho Death Records & Life Expectancy

The average age of a Camacho family member is 67.0 years old according to our database of 6,606 people with the last name Camacho that have a birth and death date listed.

Life Expectancy

Oldest Camachos

These are the longest-lived members of the Camacho family on AncientFaces.

Other Camacho Records

Share memories about your Camacho family

Leave comments and ask questions related to the Camacho family.

Anthony Camacho

Anthony Camacho  Maria Camacho

Maria Camacho A slight rain, lasting half an hour, should produce a three thousand dollars profit. A two hour thunderstorm would cost a small fortune. Whoever couldn’t afford it would die of thirst. Homer imagined his employees trying to solve the water problems of New York, the dry weather of Morocco or the need for beautiful sunsets in Bombay.

He looked at the sea and saw it full of green dollars. Green dollar was his favourite colour.

What about the waves? They should be used to move turbines and lift tractors. It was a waste of energy to have them just rolling around. They had to be classified by their size. The small ones would be worth one hundred dollars and the big ones fifteen hundred dollars. The froth should be included in the price with different colour to suit diverse tastes.

The world is crazy, Homer thought while sipping his favourite scotch. Chickens should lay their eggs in boxes and sardines ought to grow in tins. The air must be bottled and whoever can’t pay for it has to die. People without any money shouldn’t live. They’re bad for society.

They contaminate the air with their dead bodies and waste much needed food. We’ll get rid of the unemployed, when the air is controlled by a worldwide association of proletarians. They contaminate the planet with their bodies and their rubbish.

That control should have another positive effect. People who can’t buy the air, should die in special sanatoriums and their organs used for transplants. The poor things would get money for something they don’t need anymore.

Homer’s anguish trebled as he thought of the passivity of matter, people’s laziness and the indifference of galaxies.

Nasa spends billions of dollars sending humans to the space station and probes to the moon and Mars. Half of that money would buy Manhattan and part of the Hudson River to charge the toll, or a fleet of ships to look for oil in the seven seas. They could purchase The Vatican and convert it into the biggest museum in the world, or rebuild the Chinese wall with neutron bombs. Homer would build his home inside there and empty the yellow sea to fill it with dollars. Why did they have to go to the moon?

He felt that anguish again. It had to be a sign of superiority. Some men were under God’s tutelage while others had bad luck.

Homer had been born poor by accident but was guided by divine inspiration since his birth. He didn’t remember his father. He had been a man without limits, a man without space. His mother on the other hand had acquired a profile as vigorous as that of Washington in the dollars.

She had told him a funny anecdote. One day he had flown. He remembered that event with mixed feelings. As he started to crawl, he saw a dirty dollar that had fallen from somewhere. It whirled around the patio propelled by the wind.

The dollar went up and down and span around. Baby Homer looked as the piece of paper flew like a butterfly and was entangled in the branches of a tree. The child couldn’t take his eyes away from the money. He flew up there to rescue the dollar and put it in his wet nappies. Everybody thought he had God’s blessings. He must be an angel because the wings of angels had been invented to rescue money from trees.

“Dolls,” he muttered.

He wanted to tell his mother how he felt about dollars but she wouldn’t listen.

“He wants a doll,” she said.

She bought him a few dolls but he wouldn’t touch them. Homer didn’t know why his parents never exploited his qualities. They let him walk like anyone else and never put dollars by his eyes or his wings.

They didn’t see the money anymore after the incident. Confusion reigned in the region and it became part of another country.

Nobody knew where she or he had been born. More than three countries disputed the honour to have been Homer’s place of birth. He was a hero and in some ways greater than his Greek counterpart.

The chain of his existence might have been interwoven by a benevolent God who wanted him to gain glory. The fact that he had no country was an advantage in his life. If you don’t have a country, you can be a citizen of anywhere in the world and without any inhibitions.

Homer thought as he finished his glass of scotch. Schools should finish. Why did they teach children so much rubbish? I never learned anything and most of the wise men in the world are my slaves now. Many documents accredit my relationship with the best universities while hundreds of papers signed by the pope and his dignitaries show that I have bought a place up in heaven.

Homer had never been to school. His parents had gone to South America some time ago. It looked from afar as a place full of gold and fools. The first was a lie but the second one turned out to be true.

He didn’t have time to learn his own language and never spoke Spanish properly. He said a mixture of things but everyone managed to understand him. He seemed as ignorant as his Greek counterpart.

Homer remembered the first few times he had appeared in public. He had gone to the ugliest part of the city with a suitcase in each hand. He sold his merchandise on easy terms to men who were hungry, had syphilis or tuberculosis. He reminded his customers of all the pain, suffering and sweating his goods had cost him. He had paid for them in cash but they could do it on credit and without any interest.

Homer thought he shouldn’t give anything free to poor people. That had been one of the strongest pillars of the economy. Rich people look after their money, while the poor like to pay their debts. That’s the reason they remain poor.

Homer’s business improved. He hired a boy to pull a cart with a few battered suitcases while he marched in front of it. Homer sold brassieres, trousers, table cloths, woven textiles from exotic places and colourful beads against bad luck. Sometimes he used a bicycle to collect the money his poor customers owed him. He cried if they didn’t pay, and his laments would soften the hardest person. Engineers should use them to build better roads.

As time went past, Homer looked half starved. He wore rags but the notes grew in his purse. He counted his money every night in the dilapidated room he shared with other people. It had a strict timetable. A man, his wife and four children lived in it up to eleven o’clock in the evening. They had to look after a factory afterwards. At three o’clock in the morning it was a cafeteria for the bus drivers and at three in the afternoon the workman and his family came back again. Homer slept for four hours in the room. He didn’t have any trouble falling asleep and counted money in his dreams. He sold his food for the rest of the night and slept on his seat when he didn’t have many customers.

One day Homer had a shop. He called it: El Baratillo. It was between a café in the central market playing tangos and rancheras twenty four hours a day, and a drugstore where nonqualified doctors prescribed medications. A fish shop in front of it had a smell of putrefaction that stuck to the clothing. It gave Homer an additional advantage. He didn’t spend money in water and soap.

The country had been declared in state of emergency and anyone caught in the streets after eight pm was arrested. They had to stay in jail until six o’clock in the morning. Then Homer became a cook. He made delicious hamburgers of dog meat and as good as the ones made of beef. The police detained him with a basket full of food.

He slept the night in prison on a few boxes and covered with rags. It seemed better than his usual room. He sold his food to the other inmates.

“El baratillo” became an institution. A neck tie that cost forty pesos was sold on credit at fourteen pesos and fifteen cents. A dress of four hundred pesos could be reduced to one hundred and twenty and the same with everything else.

Homer hired an old bicycle to visit the houses of his customers and collect the weekly quotas. He swept and tidied his small bedroom and paid himself a tiny wage. He drank a cup of tea with a bit of cheese on Sundays and sometimes switched his light on before he went to sleep.

One day something happened that changed Homer’s life. It started in a simple way like all the great things in the world.

An Indian with high cheek bones, long black skirt and his hair in a pony tail had come in the shop. He looked like one of the figurines of San Agustin, as he stood against the dirty white wall. He remained there until the last client had left the shop.

He invited the businessman to the darkest corner of the room after checking they were alone. Then he opened a greasy bag.

Homer saw an Indian’s head reduced to the simplest expression. It had its eyes shut and its mouth had been sewn. The head was cleanly cut whilst the hair went down to what had been its shoulders. Homer felt attracted and repulsed at the same time.

The head looked like its owner and anyone would think it was his son. It seemed like a transistorised man’s head. Homer thought he had discovered something never imagined. Balboa must have felt like that as he set eyes on the Pacific Ocean, or Columbus when he shouted “Land” for the first time. In a moment of generosity he invited the man to a cup of tea.

The Indian accepted the invitation. Homer marvelled at the similarity between the Indian and the small head.

Children should play with reduced men instead of artificial toys, Homer thought as he sipped his insipid tea.

He tried to obtain more details from the Indian, but the man hardly spoke. Homer’s questions were answered by the Indian’s silence. They agreed by gestures, on a price for the head.

Homer gave him a few bits of cloth he had been unable to sell. He promised an Inca treasure if the man came back again.

He put the small head in a padded envelope, and mailed it to a friend in the USA the next morning.

They received it with deserved honours in the great country of the north. One of the most respectable houses of the Fifth Avenue asked for ten thousand more heads and they would pay a good price for them.

The Indian’s second visit to the shop happened a few weeks later. Homer led the man to his private room and gestured to his only chair.

As the Indian opened a parcel, another head appeared. It seemed almost identical to the first one. Homer gave a bag to the Indian. The man looked inside and his eyes widened.

He stood up and hopped around the room. Then he put the bag in his satchel. Homer offered an infinite quantity of coca in exchange for heads. He sounded logical. The Indians could be rich in coca if they wanted to.

He found out where he could meet the chief. He would take a few sacks of coca.

Homer’s name appeared in the newspapers for the first time: Foreign businessman wishes to visit savages. The article said Homer would like to take civilisation to the hidden corners of the tropical jungle.

The Indian came to the shop a few days later and waited for Homer to finish doing business.

Homer packed a few things in a suitcase. He shut the shop and followed the man. They boarded a bus that left them at the edge of the jungle. Homer looked with curiosity at the undulating plane full of trees.

“Will we go by car?” he asked

The Indian gestured to a few mules munching the grass. Homer had never ridden on a horse or a mule before. The man put the cases on one of the beasts and helped Homer to get on his animal.

They left the town and moved along the plain. The Indian rode in front while Homer tried to make his mule move. His body hurt with every step the beast took.

They went through the jungle at a slow pace. Homer didn’t care about the mosquitoes or the snakes. He had his mind set on the Gringo’s dollars.

He lost count of the days they moved through the jungle. They slept in a tent during the nights and the Indian made tea on a fire in the mornings.

“We are near,” the man said one day.

It was the first time he had spoken a whole sentence. Perhaps the jungle made him talk.

Homer’s bottom was black and blue and he walked like a cowboy. He had to sleep on his back in the evenings. He felt like a conquistador trying to bring the light to the wild parts of South America.

A small man waited by a hut in a clearing. He vowed in front of Homer.

“The chief is pleased to meet you,” the Indian said.

Homer dismounted from his mule and staggered towards a seat, as the two men spoke in another language. They looked at him.

“He wants to talk about business now,” the Indian said.

As Homer wiped the sweat off his forehead, the chief offered him a cup filled with a clear liquid. Homer almost choked on it.

“It’s the chief’s liquor,” the Indian said.

The interview took place amongst the trees. It was between Homer, the Indian, the chief, three snakes and thousands of mosquitoes.

Homer opened his case and put the bags of coke on the floor. The chief mumbled something after smelling the powder.

“He thanks you for God’s mineral,” the Indian said.

“Where are the ten thousand heads?”

The Indian translated and the chief gestured to a bag on the floor. Homer opened it and saw three heads. The Indians could only count up to one and anything over such a figure didn’t exist.

Homer had to teach them how to count. He explained to the two men that other numbers existed apart from one.

He put a finger up and said, “One.”

They did the same thing and Homer tried with the number two. The chief put two of his fingers up and said, “Two.”

Homer smiled. “It’s good.”

“It’s good,” they said, with three of their fingers up.

“No,” Homer said.

The chief showed four fingers, “No.”

Homer had to start with number one again. Two hours later the men had learned to count up to ten. He told them that ten thousand would be many times ten.

He gestured to the coke. “I’ll give you ten thousand bags if you bring me the same amount of heads.”

“We don’t have so many Indians,” the Indian said.

Homer gestured to a depression on the jungle floor. “If you fill all of that with heads, I will bring as much coca.”

They seemed impressed with the amount of coca Homer had promised them.

The Indian boiled some water and Homer treated them to a cup of tea. The chief sipped his drink and looked at the coca in the bag.

“The chief is pleased,” the Indian said

Homer needed many heads. All the heads they could find had to be sent to him. They would get a similar quantity of coca. He slept that night in the chief’s hut and dreamed with the heads. They chased him all over the place, while muttering something through their sewn lips.

He woke up to the sounds of the jungle and under a cloud of mosquitoes. After a bit of breakfast the chief had prepared, Homer got ready to go back to civilisation.

“The chief’s town is a few minutes away,” the Indian said.

Homer frowned. A town meant many heads and they would bring dollars to his pockets.

“Can I see it?” he asked.

The man conferred with the chief and nodded his head. They led him through the vegetation until Homer could see more huts. A few children appeared while dogs barked.

As Homer looked at the naked people, his eyes widened. He could sell them his merchandise but the heads were more important for the moment.

They packed their things on the mules and left later. As the donkey trotted along the path, Homer looked at the three heads inside his bag. He hoped to get many more heads. The gringos would like them.

He felt satisfied even though his body ached. He expected to earn good money from this transaction.

The papers spoke of the young foreigner. The citizens of the country didn’t care about the jungle, while Homer had gone to meet the indigenous population.

The heads started to arrive at the shop and the coca travelled through the rain forest to the chief. Homer had mailed two thousand heads to the US by the end of the year. They belonged to a neighbouring tribe where only two hundred people had escaped with their lives.

Homer was angry. The country had earned money with the Indian’s effort, now they said the heads had finished. A foreigner sacrificed his life to better the country while the citizens slept.

The Indian appeared in the shop again. Homer took him to his private room and gestured to his only chair.

“Did you bring any heads?” Homer asked.

“No one has died.”

“Couldn’t you kill a few enemies?”

“We don’t have any wars,” the Indian said.

Homer thought the Indians had to steal the neighbour’s cows or their women. That might start a war. The man left the shop in silence as his tribe would suffer if the coca stopped.

The heads kept on coming. Homer earned money from the shop and the heads gave him dollars. He acquired fame as an exporter while earning his rights as an importer.

He didn’t see the Indian again. A man with a basket covered in a cloth came to see him one day.

Homer finished serving his customers and shut the shop. As the man pushed the cloth away, he saw two small heads and a piece of dirty paper with something written on it: Mr. Homer. We send you the last two heads of our tribe. They are the chief’s and my own. Bye.

Homer recognised the Indian who had made him happy. The man’s lips had been sewn together. It looked superfluous. He had not spoken much during his life.

Homer gave a few pesos to the man and shut the door. The business had come to an end. Nothing is eternal and the Indians only had one head.

Heroes never give up. Homer had seen the sea in his dreams whenever he went to sleep. It could be an ancestral calling as his forebears had sailed the seven seas. The Indian adventure had earned him respectability amongst the business community.

Homer borrowed a suit. Then he gave a talk in the local library about the importance of the sea.

“We used to have two large coasts filled with maritime treasures. I love the sea,” he said with tears in his eyes.

A few people in the audience also cried. They thought he remembered his country. Homer promised to have the best ships in the world. He finished and people applauded.

Many articles in the newspapers spoke of the foreign businessman travelling in the back of a truck to the nearest port.

Homer owned small vessels at first. They had exotic names: Atenas, Esparta and The Termopilas. The sailors put fish all over the ships. They would smell like proper fishing vessels, even though they never caught anything. Homer had the aroma of fish from the shop near El Baratillo.

Homer never set foot in one of his own vessels. They were not safe and defied death by immersion. That’s how doctors without a degree call death by drowning.

Homer’s boats didn’t go fishing. He had good international relations because of the business with the heads. The boats brought contraband along the river to be sold in his shop.

Homer lived the same way as before. He slept on a few boxes and drank his cup of tea with a bit of cheese on Sundays. He woke up during the nights and barked, while walking around his room. He acquired a lot of practice and sounded like a pedigree German shepherd.

Homer punished himself if he forgot to sweep the room. He reduced the amount of tea in his cup. It played havoc with his health and he nearly fainted sometimes.

Homer worked very hard. He was his own boss, secretary, and accountant. He had to do his own cleaning, cooking and guard the premises as a dog.

He didn’t feel well. He went to see a doctor who treated poor destitute orphans for free. Homer was also an orphan.

The doctor said Homer suffered from bad nutrition. He had to eat but food cost money and he couldn’t afford it.

Homer wrote a letter to himself and asked for a substantial increase in his own wages. He didn’t have an answer as he had to travel to the port that afternoon in one of his trucks full of merchandise. He always travelled on the boxes. He would admire the view and could have a free shower if it rained. He absorbed great quantities of free vitamin D, if it was sunny.

He had good luck this time. Somebody who travelled in the driver’s cabin had a dog. The man gave Homer some of his lunch to feed the animal. Our man ate everything. He had not had such a nutritious lunch for a long time.

He felt much better that afternoon and had an erection while trying to sleep in the back of the truck. He masturbated.

It’s cheaper than doing it with a prostitute, Homer thought as the sperm ran over the boxes. Why didn’t he marry himself? Then he might increase his own salary.

Homer’s Industries answered in an unexpected way. He wrote a long declaration of love and proposed marriage to himself. He thought about it for a whole week but the hunger made him answer yes.

The ceremony was solemn given the circumstances. One of his sailors brought two salted fish from the port and bread with cheese for his wedding party. The recently married man went to the doctor complaining of stomach pains.

“You were starving yourself,” the doctor said. “You have to eat slowly at first.”

The situation of our young executive improved after his marriage. He ate fish, meat or even eggs three times a week. He looked healthier and masturbated often.

Homer made a lot of money. Taxes had also gone up in spite of all the tricks he used. He could feed himself for ten years with the money he spent in tax.

His brain started to work. Up to now he had lived following the right path. He said he would go to the jungle and everyone supported him. He had sent the heads to the US. He noticed the sea and now his boats sold contraband.

The country went through a bad patch. Every day men, women and children appeared dead and nobody cared. Genocide became one of the national industries just as football and politics.

Widowers with a lot of children were numerous. Why didn’t anybody help them?

Homer’s eyes filled with tears. He had another ingenious idea. As he cruised the poor parts of the city in his old bicycle, he wanted to find land to build houses. They would be called: “Poor Widow’s Housing.”

He found a cheap place to buy. It lay in a low plain without any water, light or sewer. He paid for some houses to be built while the weather was good. Each unit had three rooms with a muddy floor and no toilet.

As Journalists heard of the new widow’s helper, Homer became more famous than Saint Francis of Assize. The papers spoke of the five chalets destined to redeem the widows of the violence.

The bishop was a practical man. He accepted Homer’s project after a few concessions. He wanted to elect a young widow for a pastoral mission. She had to be younger than twenty five years old.

The bishop wrote the following letter to be read in the church for a few consecutive Sundays:

Dear children.

Our flock has been invaded by the wolves the scriptures talk about. Atheists and sinners try to lead astray the herd God has given me.

You have witnessed my efforts to kill those wolves. It seems as if the earth throws them out in major numbers every day. These atheists are the antichrists the scriptures talk about but hell will teach them a lesson they’ll never forget.

Assassins without any faith kill men, women and children. Our churches have been filled by orphans and poor widows who ask the heavens for retaliation. God will punish the sinners just as he did the Egyptian children.

That is why you must be afraid of his anger. You must repent of your sins. If the Devil appears from the abyss the angels can also come from heaven. God hasn’t abandoned us yet.

A foreigner called Homer has dedicated his life to help the widows and orphans of the violence. We mustn’t let our angel alone. We need the solidarity of God’s people to win over the darkness. We want your charity to erase the most despicable sins against these poor people.

I’m asking you to send money to our Episcopal palace. You must forget material interests that won’t serve in our present life. This is a temporal place before our real country up in heaven or down in hell for sinners. Perhaps they didn’t help their poor brothers or sisters.

We must support Apostle Homer in his angelic functions. You will have God’s blessing for every million pesos you give.

His Highness

Pomponio

Bishop

The letter his holiness wrote had a good effect. Homer received many times the money he had spent in the houses in a few days, even if the bishop kept more than half of it. The bishop had to reprimand a few priests who wanted a percentage of the earnings.

All the local newspapers published editorials exalting the qualities of Apostle. Homer. He gazed at the distance in the pictures as if looking at God’s face instead of a million pesos. The mystical breakdowns of Saint Theresa might give us an idea of Homer’s face before the cameras and the television.

The citizens filled millions of petitions asking for social solidarity. The governor with all of his cabinet marched to the Widow’s Houses. He gave materials for construction and money to Homer.

The Widow’s Soup was served in the most exclusive restaurant. The beauty queen of Colombia, the queen of the potato, the yucca, the corn, the banana, the pea, the pumpkin, the yucca bread, the tamales, the guarapo, and a hundred beauties of the city served the four thousand guests.

Each person had a bowl filled with boiling water and a cold bread for the sum of one hundred thousand pesos. Rich people from the city could be seen amongst journalists and television cameras. They hoped that God would absolve their past sins and those still to come.

Homer read a few lines of the Old Testament and spoke for five minutes. As he talked of the widow’s pain, his eyes filled with tears. He had learned how to do that without much effort.

The band played the national anthem amidst the public’s ovation.

The beauty queens filed in front of Homer and kissed his hand. They left it full of tears and saliva. People in the restaurant sobbed. Radio and television’s audiences cried. The readers of the newspapers cried the next day and the poor widows wept. Homer shed tears of happiness in his dilapidated room. He was a genius.

He had never seen such a show of solidarity. He made enough cash to build a city filled with poor widows but he needed the money.

Five more huts joined the others while some young and pretty widows who liked the bishop, went to live there. Homer had never earned so much and so quickly. He became more popular than Sister Theresa and Saint Francis of Assisi.

It rained hard. Some widows and orphans drowned but the newspapers didn’t say anything. Nobody paid for the burial and the wooden coffins were lowered into the ground without any ceremony.

As the waters left, a few young widows moved into the huts amidst praise for the apostle.

The widow’s business didn’t just give cash but it generated great publicity. It benefited the smuggled goods and taxes.

Homer asked the deprived mothers to sign documents. Most of them couldn’t read or didn’t want to know why they had to sign.

They thanked the benefactor who gave them a roof over their heads and some food. It wouldn’t let a rat die of hunger.

The papers the women signed left Homer out of reach of the income tax. Homer’s expenditure became far greater than his earnings, according to the certificates. He had done all of this to sustain the poor women.

The widows’ food grew to be the largest business for our man. He brought lots of merchandise into the country every month. The boxes had a cross on them. It said in big red letters: Charity. This food is for the poor of Colombia. Look after it!

The boxes went past the customs without any problems. Sacks full of wheat went through customs sometimes, but they usually contained goods. Sport cars were smuggled with ‘frozen food,’ written on them. Any food sent in the packets would be sold at high prices to Homer’s customers.

His ships brought Swiss watches, Scotch whisky, French Wines, tinned food from all over the world, televisions, videos, pants, bras and other things.

Homer’s modest shop became a world bazaar. You could find a Mercedes Benz or fine French pants. Custom officials never wondered about so many expensive and rare things. They didn’t doubt Apostle Homer’s behaviour. The public would attack them, it they examined his business. They couldn’t bother someone as nice as Homer. He gave them whisky, cigarettes and lighters. Sometimes he sent them cheques of a few thousand pesos for Christmas. What a remarkable man!

The old boats: Athena, Sparta and The Termopilas had been replaced by three new and powerful ships: Odysseus, Ayax, Diogenes and Cyclops. They traded in goods.

Homer slept better during the nights. As he lay on his boxes with a few rags on, he counted and recounted the day’s earnings. His food improved. He drank a cup of tea with a portion of rotten cheese three times a week and had three suits bought in a second hand shop. He looked much better.

He stopped barking for a few nights. One of the widows gave him a dog but it didn’t have Homer’s deep voice.

The animal had a bad habit: it ate. Homer trained it to live without food but the dog died.

Our man walked around his property barking again. He did his job very well. A neighbour paid two thousand pesos for Homer to bark in his patio during the night. He accepted the job and used the money to buy some meat. His food improved even more.

He had a crisis at this time. He felt in love with a girl for some reason. How could it be?

As he saw her on his way to his room, he had a shock that ran down his spinal cord and ended in his genitals.

“What a woman,” he muttered.

He followed her along the streets and up to her home. He didn’t know what to do. He masturbated several times that evening. He had to buy two extra eggs the next day in order to feel strong.

He waited for her in a corner the next day. She looked like a good contraband when he saw her coming.

“You’re as beautiful as a million pesos,” he said.

He didn’t feel well, perhaps because he had masturbated the day before or the thought of a million pesos. The two things made him as pale as an anaemic flower.

Lola worked at a beauty shop and earned enough money to buy clothes and food for her and her mother. Lola had a perfect body and any clothes she put on seemed superfluous. She looked better than a duchess even if she dressed in rags.

She rounded her meagre wages, calming the amorous needs of a few sergeants. They were her favourite dish. She had seen Homer a few times in the television, and her feminine intuition told her that he wasn’t a poor Franciscan.

Lola had loved a few members of that community and knew they had money. She liked to mix sergeants with clerics.

Homer was a young man who had a few ships. He didn’t look like superman but he wasn’t Frankenstein. Add a few million pesos to all of this and any woman would fall in love.

“Can I walk you home?” he asked.

She could see how pale he was. She pretended to be shy and shook her head. Homer couldn’t follow her anymore as his legs felt like jelly.

He didn’t sleep that night. How could a man of his quality fall for that silly girl? Every time he thought of the girl he barked in his neighbour’s patio. Then he went to sleep without much trouble.

He had to travel in one of his trucks the next day. He thought about it. What about if the driver stole something? He could do that kind of thing often and waste petrol. He could even bring his girlfriend. How could Homer see Lola and look after the trucks at the same time?

He surprised himself as he waited on a corner for Lola to appear. He should be behind the counter of El Baratillo or in the port as his ships loaded or unloaded their merchandise.

The girl was late. Homer’s hands sweated and he wanted to go to the toilet, when she appeared in the corner. She looked as beautiful as ever.

He checked his clothes and found them all right. A friend had lent him the suit. The trousers seemed a bit large but they looked fine so long as he kept his coat on.

“Miss,” he said. “Can I walk with you?”

He had thought of this phrase for a long time and said it with elegance.

Lola blushed like a shy school girl. “My mother doesn’t let me take anybody home.”

Homer walked by her side. She had a spiritual quality that he loved.

“I work hard to pay the debts,” she said. “I make dresses at home to earn extra money.”

He shrugged. “I’m also poor.”

He was madly in love with her. It had to be love at first sight like they said in the soap operas.

“My mother can’t see you,” she said.

As Homer left, a sergeant waited for her a few streets ahead. He took her to the cinema but Lola didn’t behave very well. She kept the militaries and the Franciscans away from her, as Homer’s money seemed more important. She wanted to own a few ships. She dreamed of rude sailors making love to her in taverns, smelling of whisky and fish.

Homer thought he would go mad. That night he barked aloud and the neighbours complained. He kept them awake the whole night.

Lola learned of Homer’s apparent poverty and body lice. Our businessman had as much life on his body as he had money. He only used water and soap for shaving himself and washing his hands. Couldn’t she change him with her charms?

She liked to spend money. Her husband could work all day while she enjoyed life. She let Homer take her home the next day and introduced him to her mother.

“I like your house,” Homer said.

“It’s small but we are poor.”

Homer held her hand. She smiled and kept her distance because of the lice.

“I live in a hut with my dog,” Homer said.

Lola’s mother thought her daughter liked to have strange boyfriends.

Homer left an hour later. Fray Serapio had waited under the bed and developed rheumatism since that day.

Homer bought a new suit. Then he bought soap and had a bath. He had never done so many mad things on the same day.

Lola kept away her other lovers. She went to work, did her shopping and even slept alone. Chastity might be a good business sometimes.

You know where to start when you are in love but you don’t know where it will end. Homer’s madness became worse. He invited Lola to have an ice cream that afternoon. The girl chose an inexpensive shop and had the cheapest ice cream. He liked that. Lola could be his business partner as she didn’t waste her money in colourful ice. Homer had a glass of cold water.

He forgot to bark that night and lost a few thousand pesos. The two employees at El Baratillo and the crews of his ships couldn’t believe the change in him. They had never seen Homer clean. He travelled to the port only once a week and sat next to the driver. He didn’t sleep on the boxes but at a hotel that charged a few hundred pesos per night, sharing the room with someone else. Everyone thought he had gone mad.

It didn’t end there. He bought a small coconut when he returned to the city. The taxi driver asked for a piece of the hard skin to keep as a treasure. It should bring him good luck. Homer had never done anything like that.

He gave Lola the coconut that evening. She thought this was just the beginning. She didn’t have the priests or the sergeant anymore and kept Homer at a distance.

As he tried to kiss her, she stopped him. The coconut had not been enough. Homer thought she was a virgin.

He slept better and did his job as a guard dog. The rest of the time he reproached himself. Why had he spent so much money with the girl? What use did it have?

These questions kept on repeating themselves in his head like characters in a nightmare. He couldn’t find an answer. Why did he give her the coconut? He could have fed himself with it for the whole week. The ice cream had been water with a bit of taste and colour. He had wasted water having a bath as well as the new soap he had bought. He had to think in his water bill and in the money he had paid to the hotel in the port. He must be losing his mind.

He felt afraid of mad people since he had been a child. His mother had shown him people eating, drinking and spending money. They had to be crazy. He remembered fiends without a form and infamous animals moving through the streets. They were mad.

People who took care of their money looked fat and healthy. They were not crazy. Homer didn’t look very healthy.

He still wanted Lola in spite of all of this. He missed her firm breasts and her sex appeal. His body floated like a shipwreck survivor in a typhoon. He masturbated repeatedly and dreamed of an immense muddy lake full of bits of women and dollar bills. He had been destroyed by sex, mud, sex and mud.

Homer felt terrible the next morning. He couldn’t get up from his boxes to boil the water for his cup of tea. His employees found him later. He had hurt his face.

They wanted to take him to the doctor but he wouldn’t hear about it.

“No,” he said. “I don’t want doctors. “They charge a lot of money for nothing. I only want a cup of tea.”

His employees collected some money and bought milk and brandy. He felt much better. Then he found out what he had and felt ill again.

“You don’t have to pay for anything,” one of his employees said. “It’s a present.”

Homer smiled. The neighbours sent meat and eggs soup to their dear ‘dog’ the next day. As the widows learned of his illness, they sent him chicken soup. They wished for him to get better and prayed for his recovery.

The man had not eaten so well in his entire life. One of Lolas’ clerical friends found out about it and told Fray Serapio. The man had suffered lumbar pains because of Homer’s visit to Lola. He told her that poor people had helped her greedy boyfriend. What could she want with someone like that?

“I thought Homer was a good man,” Lola said.

She phoned the sergeant.

“Can you take me home today?” She asked him.

The man sighed. “You have your rich boyfriend.”

“He’s not my boyfriend anymore.”

“I don’t believe you,” he said.

The sergeant appeared as she left her job. They walked down the road while Homer stood in the corner.

“Hello,” Homer greeted.

The sergeant punched him and swept the street with Homer’s clothes. He made Homer’s life more tragic. His body was sore and his clothes had been torn.

He tried to sleep on a sitting position on his boxes that evening. He couldn’t bark, thinking of the girl’s ungratefulness.

He had given her a bit of coconut and ice cream, but she had let the sergeant beat him up. All women had to be like that.

The widows sent him a nutritious breakfast the next morning and things looked better. As his friend came to collect the suit, he heard of the harrowing moments when a bus had knocked Homer down. He didn’t accept any money for the ruined suit.

Homer calmed down and spent a few days on his boxes. He hated all women and their sergeants. An employee found a mattress next to Homer’s place of death. Sorry, next to his place of living. He repaired it a bit and took it to Homer’s room.

Homer liked it. It was better than the boxes. He dismissed his employee the next day in case he wanted a salary increase.

He had lost a lot of money. He had not been able to bark or to keep an eye on his workers. He had lost a fortune in a few days without counting the coconut or Lola’s ice cream.

Bad things never come alone. It rained that night. Seven widows and eight children drowned in the widow’s houses. One of the women had been the bishop’s favourite. The egg soups stopped coming.

The world had been at war for a few years. It was called a war world and Homer’s old country was invaded.

He had made money out of the Indian heads, the widow’s pain and the orphans. Could the invasion of his dismembered country be another business?

He travelled to New York in one of his own ships. They didn’t have a waiter and Homer took the job. He could earn pesos and have food for a few days.

One of his friends in New York found a job for him in a bad restaurant. Homer rented a room for a few dollars. He lived much better than above El Baratillo.

He made contact with a colony of people from his country. The invasion of their land made them angry, even though it had been invaded many times before.

Homer became the fire of the revolution. He would put his life in danger and lose a few ships, before the enemy set feet in his country.

Democracy filled him from head to toe and he didn’t speak of anything else.

“I have abandoned my second country for the price of love and freedom,” he said to his friends.

They were impressed. He didn’t have a coat for winter and slept without a heater. He would leave his bones here if it was good for his countrymen.

The gringos liked Homer. They thought they could use his ships to help the soldiers from his country. It was a dangerous thing. Instead of dying shouting in New York, he would do it at the bottom of the sea. The USA government would give him free arms.

All of Homer’s ships had been put at the service of the war. He cancelled his businesses in Colombia including El Baratillo. The Widow’s houses had disappeared under the water a few moths before and its inhabitants drowned. Homer was a warrior now.

Odysseus could be the first ship to leave port. It was surrounded by absolute secrecy. Homer would be the captain of the boat for the first time. He had an artificial moustache and looked like an old Turkish sailor.

He saw the workers putting things in his ship. Machine guns arrived in boxes, bombs that looked like corn on the hob and munitions disguised as chocolates. Canons pretending to be canoes and a few tanks camouflaged as ambulances.

Homer left New York in a misty morning. He saw a new adventure in the horizon. It might be more productive than his past enterprises.

He had started his life as a diplomat a few months before. He obeyed his instincts and his manner had been softened. He acquired a psychological saturation comparable to that of Fouche or Nicholas Machiavelli.

The Odysseus changed its course once it was in the high seas. The sailors thought Homer wanted to confuse the enemy submarines.

It didn’t have anything to do with submarines. Homer had already sold everything at a good price, as South American governments needed the arms urgently.

The foreign gentleman reminded them of the legends of Viracocha as an airplane had thrown him out of the clouds. He offered the government a small arsenal. The mysterious visitor wanted to bring democracy to foreign lands to help with the war effort. He wished to take the bleeding flag at any time.

The governors, who had made the flag bleed for some time, accepted the offer to keep some of the earnings in their own bank accounts.

“We’ll be helping the country that way,” Homer said. “We fight for democracy and make a few cents at the same time.”

The Odysseus left its precious cargo in the Caribbean while the storm went on in rest of the world. They spoke of Homer’s heroic behaviour in New York. They had lost trace of him. Perhaps the sea had taken him away forever.

Homer came back sunburnt and with bananas and dried caimans. He brought a few messages from the anti Nazi warriors. They wanted to have some more arms.

They organised another expedition with four of Homer’s ships, who had shown a great ability to avoid enemy submarines.

He took more things than the first time: tanks, bazookas, anti-tanks canons, machine guns and a lot of ammunition. Two small aeroplanes completed the arsenal.

The fleet sailed around the sea taking care of enemy submarines. A bigger and more powerful South American country received the armament this time. It declared Homer as its national hero. The government kept the secret and its dignitaries became richer.

One of Homer’s boats sailed towards the Mediterranean Sea with a few old tanks. It sunk and the sailors died.

Homer’s friends in New York couldn’t believe it. They prayed for Homer’s soul in Colombia. He had become and hero and as the night neared its end his name was in everybody’s lips.

Homer heard the news in a tropical island. Wearing a wig and false nose, he went to the nearest port. He asked if anyone had survived the shipwreck.

“No,” they replied.

He paid to be left aboard a floating ring in the Mediterranean Sea. It was dangerous but worthy.

He spent six days and nights between the sky and the sea. He had Coca-colas, caviar, brandy, good wines and a lot of cakes. On the sixth day, he threw everything overboard as a pilot radioed for help.

They didn’t come for three days. Homer looked like a real shipwreck survivor when they found him. The news went around the world. The good news caused excitement amongst his friends

A famous journalist wrote a chronicle called: Alone between the sky and the sea. It won the first prize in international journalism and the peace prize.

ALONE BETWEEN THE SKY AND THE SEA.

Cucu Fifi’s chronicle. Winner of the journalism peace prize.

The air melted over the quiet mirror of the sea. The bearded and almost naked men, whose eyes shone with resolution, knew where they had to go.

Men’s lives are like ships. They have a goal in life or they go around forever in the Sargasso Sea.

Our bearded heroes didn’t know where to go. They found their north but it really was their east. They didn’t want to remain in the Sargasso Sea amidst bits of ships. They had a goal to justify their existence.

Sometimes we hear our inner voice, the call of the ancestors or the need to adopt a definitive goal with death as its limit.

We have heroes in this world. That singular example of human being will never cease to exist for the well being of humanity. The Odysseus has stopped any doubt about that.

It had the same name as the Greek hero, because of some premonitions. As if it knew of its honourable end. Real ships aspire to end at the bottom of the sea like in the poem of Neruda.

The sailors and the ship were an arrow sent by God against the enemies of humanities. They recognised the sound of the motors and the movement of the ship in the immensity of the sea. It had become a hero’s shout caressing the water.

They sailed through the turbulent Atlantic Ocean, full of submarines and arrived at the calmer Mediterranean Sea, who after giving birth to civilisation had been menaced by man’s insanity.

Civilisation is the fruit of many years of evolution. It can’t be lost because someone decides to make Berlin as the Russian capital when everyone knows the Russian capital is Leningrad.

In such a radiant day, the heroes carried arms for their companions fighting in inhospitable mountains, turbulent rivers and bloody awakenings. They wanted to fecundate the earth with the bones of their ancestors.

In Homer’s mind appeared the foggy form of his far away country where he would leave the glorious effort of his resolution. This thought made the men insensible to the water, hunger and hard work.

The colour of wine sea that Homer sang seemed to be destined to keep in its entrails that other contemporary Homer who never sang any epopees. He had written them in his contemporary life with as much heroism as the old Greeks who had defied the danger of the unknown in their concave ships.

The modern Argonauts travelled here wishing to leave their sober existence in the cliffs where gold and freedom flowered

The furious explosion of a torpedo covered all of their dreams with flaming waves. Before their eyes, the sea turned purple and the sky a big breath of fire that ate them with indifference.

Oh the hero’s life!

Oh the tears we all pour!

Oh the mothers and lonely sons!

The captain was there like a sign in the torment. Homer, the omnipotent hero, fought against fire and death like a hard rock.

They saw him all over the ship, fighting, calming and comforting his crew. His leaden soul didn’t suffer the attack of the waves and didn’t fracture with a powerful explosion. He tried to save his men, his boat and the arms of liberty.

He didn’t remember how long he was there. He came back to reality as the ship sank. Most of the crew had gone away in the boats before the sinking ship took them under the water.

Then he saw the apocalyptic monster still smoking between the waves. The submarine shot them with its guns.

They were not alone. The intrepid captain would not let them be killed like pigs. The small canon blasted the submarine. It sank quickly but alas too late as everyone in the boats had died.

Homer wanted to die with his ship. He tried to dress himself with his best clothes but the room had been flooded. His burned lips intoned a song he had learned in his childhood. Then his rough voice sang the national hymn of his country above the dead bodies and bloody water.

The Odysseus didn’t want to die, perhaps in solidarity with our hero. As long as his heart could pump blood, the enemies of freedom would have a champion to fear and respect.

Our hero became a symbol for people suffering under the boot of the tyrant, and a hope for those fighting in the mountains, as well as for the poor women in concentration camps and the millions of slaves dying of hunger.

Homer spent a long time in between the smoky remains of his ship. He waited for the ship to sink to the bottom of the sea but the Odysseus didn’t want to die yet.

The flight of a solitary airplane brought him back to reality. Life is his passion and in this case freedom.

The sun dived behind the clouds when our hero thinking in his country and freedom went in the small boat. He swore vengeance for the blood of the soldiers floating in the dark sea.

Loneliness is the food of big souls. The quality of a hero is measured by the ability to be on his own for an indefinite time.

Homer, a tiny toy of God’s element had found himself alone between land and sea. He would be welcome in heavens for all the great work he has done. That place appeared hostile and burned him with its ardent rays. He knows very well what the almighty wants: Life eternal requires good souls purified by tears and hope.

None of us has experienced loneliness. He tried to give us a description of his suffering with his modesty.

SEA, SHARK, WHALE, SEA, SEA, SEA, SEA, SUBMARINE, SEA, SHARK, SEA, SUN, HAMMER HEAD, SEA, SHARK!!!!!!!! HOMER!!!!!!!SHARK, SEA, SEA SNAKE, SEA, SUN, SEA, SEA, SEA WOLF, SEA SICKNESS, SEA SICKNESS, SEA, THIRST, THIRST, SUN, SUN, SEA SICKNESS, WAVE, WAVE, WAVE, WAVE, BIGGEST WAVE, WAVE, WAVE, SMALL WAVE.

He drew the small picture we have seen here.

Sea, the eternal sea surrounds him, until it disappears in the horizon. A shark moves around the small boat. Homer tries to hit it with an oar but he only makes the monster angrier. He doesn’t remember for how long he fought the shark as a barracuda also came to the side.

Homer’s clothes have been torn, exposing his body to the hot sun. The shapes of his persecutors hide in the shadows of the night as he tries to sleep.

The sea turns into an enemy. He has to tie himself to the boat so that he won’t go overboard. He can’t sleep in peace for fear of capsizing.

He doesn’t remember when the sea quietened down. As he woke up later, he saw the sun high in the sky and felt very thirsty. He didn’t see any sharks because a giant whale had eaten them. The whale wanted to have the boat and its occupant for dessert.

As Homer punched the monster’s nose, the big fish fled towards the North Pole.

WATER!!!!!!!!! WATER!!!!!!!!!

He had his feet inside the water. It seemed to be a penance for big souls. Out of the water emerged a submarine and Homer shouted: WATER!!!!!!!!

It happened to be a U225, commanded by Lieutenant Fritz Wise. He found out the nationality of our hero and gave him a piece of salted fish. He left Homer in the same place, after doing the Nazi salute.

The salted fish dried his entrails and his stomach rumbled. Very soon he floated in a sea of chit.

The vomit changed the quality of the sea as time went by.

He stopped seeing the sea. He had been transported aboard a high mountain. The sun burned his skin while his entrails asked for water.

How long had he been there? No one knows. After hearing the noise of the waves, he appeared again in the sea. He realised what had happened. He had been on the head of a giant dragon that threw fire out of its mouth. The dragon had not noticed Homer’s presence and went to sleep at the bottom of the sea.

Homer prayed and remembered his mother while remaining on the boat’s floor.

He saw a light. It shone in front of his face filling it with sweetness. A voice said: Homer, my son. Our hero replied. Who is calling me?

“It’s your father who lives in heaven and will never abandon you!”

After a moment of silence even the sea went quiet.

“Heavens and earth will end but my words will go on,” the voice said.

As the light disappeared, an angel brought him something to drink in a big amphora. It tasted better the Coca-Cola.

He was fortified the next morning. He had to win. His life had been planned by God for higher purposes. He knew about it.

When the British anti-torpedo ship, Robin Hood, found him, he looked thin but all right. He had been sixteen days without any food and drink.

They all marvelled about it except Homer, who remembered the amphora and the angel.

He recalls that life without freedom and dignity is not worthy.

HURRAY TO FREEDOM!!!!!!!!!!

HURRAY TO HOMER!!!!!!!!!!

HEALTH TO THE HERO!!!!!!!!

The journalist article of the writer Cucu Fifi was translated in all the languages and dialects. Homer’s image became a symbol of heroism and decision around the world. He received a medal from the United States congress in a sober ceremony attended by the heads of many democratic countries, three hundred thousand soldiers, nine hundred thousand students and a lot of wounded and veterans of the world wars. Stalin declared him leader of the Soviet workers and General De Gaulle kissed him repeatedly in the cheeks.

Homer’s heroic temperament remained the same. His love for freedom and hate of tyrants grew more with each passing day.

Bigger ships sailed under his flag as arms were sold to poor countries in Latin America.

His creativity remained the same but his taste for clothes and manners had changed. He wore the best Piccadilly Street clothes and had finished a few correspondence courses.

He went around the tropics selling cheap autographs and smiles like a true hero. It served as an aperitif for future commercial transactions.

Love came to him in a torrent perhaps to compensate what he had not enjoyed before. For some reason all beautiful women wanted to love him. They then became celebrities.

Millionaire husbands found it pleasing to tell their friends their wives had been

Homer’s lovers. The best international high society presentation card was to love

Homer. As the world war ended, Homer had found the best way to enjoy freedom.

SECOND CHAPTER

MARIO’S LETTERS

Maria Camacho

Maria Camacho A LIFE

I’m sharing with you the life of a clever, funny and gifted writer, a man who could talk about any topic and knew everything. A father that I miss and wished he could have been preserved for eternity.

Santander del Norte was a quiet province in the norther of Colombia at the beginning of the twentieth century. It had been rocked a few times by the wars between the liberals and the conservadores during the last century. In a quiet village called Lebrija an hour away from Bucaramanga, a young woman (Josefina Camacho) went in labour. She already had two other children and had lost a few others at birth.

Little Horacio Camacho was five years old and his sister Lijia, two years old as they waited with their father outside the room. As Josefina pushed for a last time, a rose faced child appeared in the world, locks of fair hair on his wet head.

The two children outside the room heard the baby crying and pushed the door. The father, Ismael Camacho, rushed to his wife’s side and admired the new addition to the family, while the midwife cleaned the child and cut the umbilical cord.

The midwife didn’t let him near the baby. Josefina had lost another baby during the previous year. The midwife wanted to make sure everything would be fine this time. Ismael led his two other children out of the room. He gave them some lunch while the midwife made sure mother and baby were all right.

That evening little Ismael slept in a small cot by his mother’s side. The sound of cockerels singing woke them up the next morning. As the child cried, his mother put him to her breast. The memory of the other children who died young was fresh in her mind.

Jose Ismael grew up into a chubby child with golden curls. He played with his brother and sister in the countryside around his home. His peaceful childhood shattered when his father died. Jose Ismael was five years old while Ligia and Horacio were six and eight years old.

He travelled with his mother, brother and sister on the back of mules, to a town where his uncles lived. That journey across the mountains must have been exciting for a five year old boy.

It was the ninety thirties and the country didn’t have many roads. Jose Ismael didn’t remember much of his trek through the mountains. Josefina was a young woman who had just lost her husband. She wanted to give her children a better life and education.

Jose Ismael didn't remember much of that journey.

His brother Horacio did recall the slow pace of the mules throughout the mountains. A friend had travelled with them on another mule. He had a map of the region where the path sneaked through the mountains and towards the next province.

They would stop to rest and to eat their food. Josefina had brought boiled eggs, potatoes and water ion bottles. It was a big adventure for the children who had never left the town where they had been born.

They slept in a tent by a river that evening as the mules ate the grass. Their friend got up early the next morning to saddle the mules in preparation for the day.

The children played early the next morning. It was a great adventure for them all, even if the weather was a bit cold and they were tired.

They played hide and seek in the field while their mother and their friend got ready to leave.

Jose Ismael hid behind his mother as Horacio looked for him.

Josefina put the child on the mule while the man helped the other two children on the other one. She was a strong woman who had chosen to trek across the mountains to look for her family. She needed their support in this stressful time.

The mountains followed each other like an immense kaleidoscope as they went in their journey. The top of the Andes looked dark under the rays of the sun. They had left the province of Santander. The lush grass had given way to the mountains where cows and goats stood in the most dangerous places.

The mules digested their food of grass and marigolds while moving through the beautiful landscape of green vegetation growing in the steep fields. An eagle circled above looking for pray as nature rejoiced in life.

They saw the mountain vegetation as they went deeper inside Boyaca. A house made of mud lay at one side of the path while children wearing colourful ruanas looked at them. A dog ran around the mules while barking.

A woman appeared at the door and called the door.

“Where are you going?” she asked Josefina.

“We are on our way to Choconta,” she answered.

The woman invited them to go in her house to rest. It had started to rain and Josefina was glad to wait in the house until the weather cleared.

The woman offered them hot chocolate while puppies ran by their feet.

The woman gestured to Josefina’s friend.

“You’re very brave to travel across the country with your husband and children, on the back of mules.”

“He’s just a friend,” Josefina said. “My husband died a few weeks ago. My uncles live in Choconta.”

“I’m sorry about your husband,” the woman said.

The sun was shining a few minutes later.

“Thanks for the drink,” Josefina said. “We have to arrive at Choconta before the evening.”

They went on the mules while the dog barked. The animals trotted on the muddy path for a while. It was warmer and the vegetation had changed. The plants that grew near the paramos had been replaced by coffee plantations.

They saw Choconta from far away, the church steeple against a cloudy horizon. The mules sensed the end of their journey and trotted towards the houses at the edge of the town.

Josefina with little Ismael were the first ones to enter the town. People looked at them from their houses as children played in the streets.

They found the church behind the park. The sound of people singing spilled out into the surrounding streets.

Their friend helped them to dismount from their donkeys. The five of them entered the church as the priest read the sermon.

He was a little man, who pushed his big glasses up his nose as he talked.

He paused for a minute eyeing the new arrivals. Then he resumed his speech.

The priest came towards them after mass. He hugged Josefina and the children.

“I was expecting you,” he said.

He was Uncle Antonio. He was a catholic priest who believed in the kingdom of God.

Uncle Antonio helped to bring their belongings inside the church.

The man who had accompanied the family to Choconta stayed in the house that night. He would go back to Lebrija in Santander the next day.

Josefina and her children were tired after the long journey. Father Antonio took them to their rooms at the back of the house after they had their dinner.

His brother, Father Felipe met the family that evening. He had only seen Josefina once before.

He admired the young widow who had journeyed through the mountains to come to Choconta.

The uncles taught the children all about religion and the bible. The family had to move between the uncles a few times. They paid for the children’s education.

My father was 14 years old when the second war world started. He used to read everything about the conflict. He liked going to the movies to see films and the trailers of the time.

He was a clever boy, who did very well in the school. He had inherited his mother’s blond hair and fair skin. His sister Ligia and his brother Horacio looked more like their father.

Jose Ismael finished school and studied medicine at the Universidad Nacional of Bogota. He got his degree in medicine and married his second cousin, Cecilia Mogollon, on the 14 of February 1952.

Maria Cecilia Camacho (The writer of this page) was born on the fifteenth of February1953. My brother Ismael Hernando Camacho was born onthe thirty first of May 1954.

Followers & Sources