The future Renaissance man of American music was born in Lawrence, Mass., on Aug. 25, 1918, the son of Samuel and Jennie Resnick Bernstein. His father, a beauty-supplies jobber who had come to the United States from Russia as a boy, wanted Leonard to take over the business when he grew up. For many years the father resisted his son's intention to be a musician.

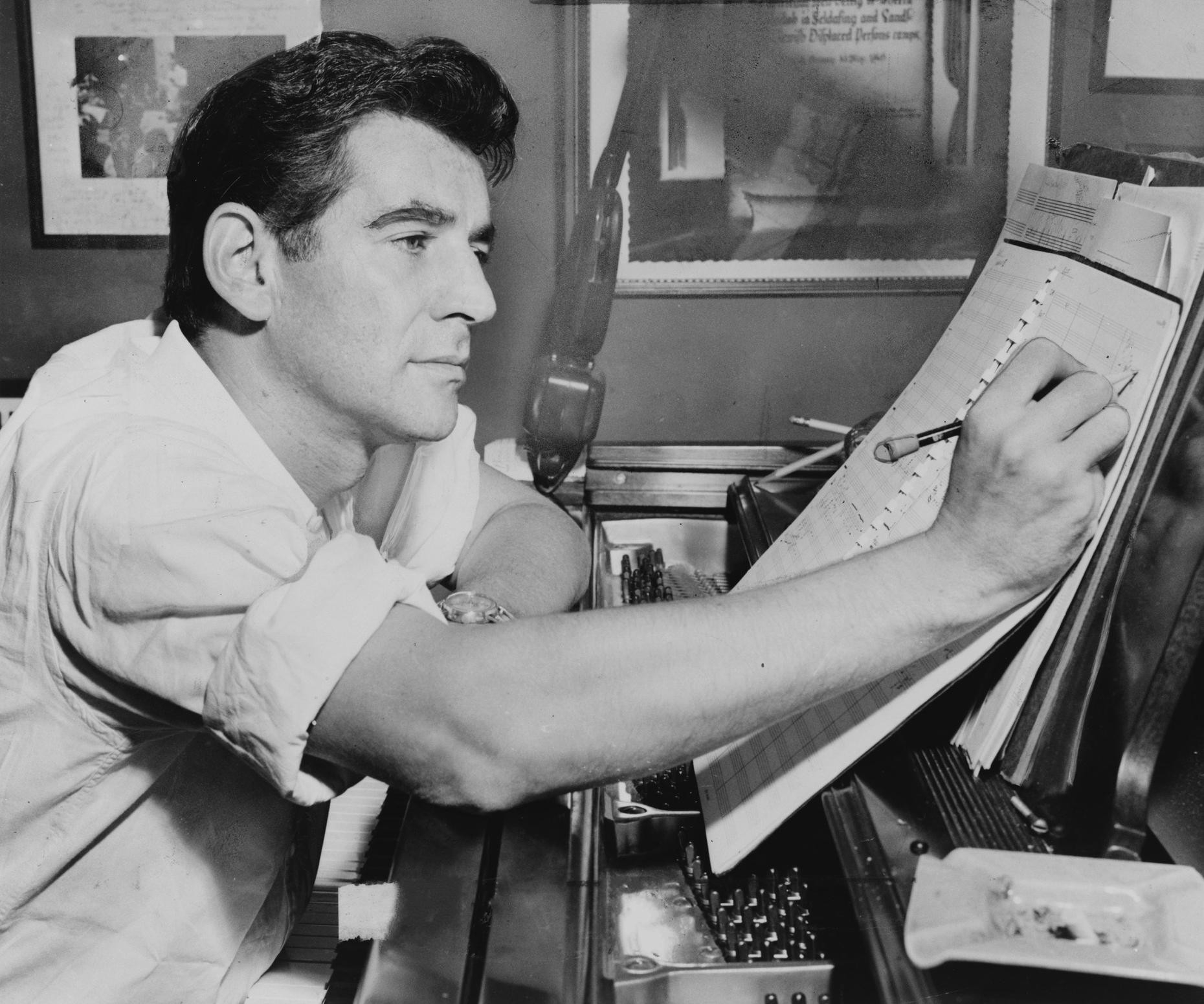

The stories of how he discovered music became encrusted with legend over the years, but all sources agree he was a prodigy. Mr. Bernstein's own version was that when he was 10 years old his Aunt Clara, who was in the middle of divorce proceedings, sent her upright piano to the Bernstein home to be stored. The child looked at it, hit the keys and cried: ''Ma, I want lessons!''

Until he was 16, by his own testimony, he had never heard a live symphony orchestra, a late start for any musician, let alone a future musical director of the Philharmonic. Virgil Thomson, while music critic of The New York Herald Tribune in the 1940's, commented on this:

''Whether Bernstein will become in time a traditional conductor or a highly personal one is not easy to prophesy. He is a consecrated character, and his culture is considerable. It might just come about, though, that, having to learn the classic repertory the hard way, which is to say after 15, he would throw his cultural beginnings away and build toward success on a sheer talent for animation and personal projection. I must say he worries us all a little bit.'' These themes - the concern over Mr. Bernstein's ''talent for animation'' and over his penchant for ''personal projection'' - were to haunt the musician through much of his career.

Economy of Motion Not His Virtue

As for ''animation,'' that theme tended to dominate much of the criticism of Mr. Bernstein as a conductor, particularly in his youthful days. Although he studied conducting in Philadelphia at the Curtis Institute with Fritz Reiner, whose precise but tiny beat was a trademark of his work, Mr. Bernstein's own exuberant podium style seemed modeled more on that of Serge Koussevitzky, the Boston Symphony's music director. The neophyte maestro churned his arms about in accordance with some inner message, largely ignoring the clear semaphoric techniques described in textbooks. Often, in moments of excitement, he would leave the podium entirely, rising like a rocket, arms flung aloft in indication of triumphal climax.

So animated, in fact, was Mr. Bernstein's conducting style at this point in his career that it could cause problems. At his first rehearsal for a guest appearance with the St. Louis Symphony, his initial downbeat so startled the musicians that they simply looked in amazement and made no sound.

Like another prodigally gifted American artist, George Gershwin, Mr. Bernstein divided his affections between the ''serious'' European tradition of concert music and the ''popular'' American brand. Like Gershwin, he was at home in jazz, boogie-woogie and the cliches of Tin Pan Alley, but he far outstripped his predecessor in general musical culture.

In many aspects of his life and career, Mr. Bernstein was an embracer of diversity. The son of Jewish immigrants, he retained a lifelong respect for Hebrew and Jewish culture. His ''Jeremiah'' and ''Kaddish'' symphonies and several other works were founded on the Old Testament. But he also acquired a deep respect for Roman Catholicism, which was reflected in his ''Mass,'' the 1971 work he wrote for the opening of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington.

A similar catholicity was reflected throughout his music. His choral compositions include not only songs in Hebrew but also ''Harvard Songs: Dedication and Lonely Men of Harvard.'' He was graduated in 1939 from Harvard, where he had studied composition with Walter Piston and Edward Burlingame Hill.

A sense of his origins, however, remained strong. Koussevitzky proclaimed him a genius and probable future musical director of the Boston Symphony - ''The boy is a new Koussevitzky, a reincarnation!'' - but the older conductor urged Mr. Bernstein to improve his chances for success by changing his name. The young musician replied: ''I'll do it as Bernstein or not at all!'' He pronounced the name in the German way, as BERN-stine, and could no more abide the pronunciation BERN-steen than he could enjoy being called ''Lenny'' by casual acquaintances.

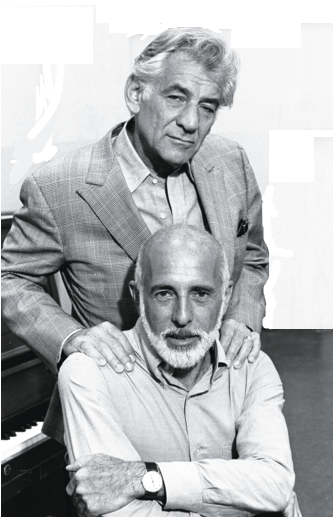

In addition to his children, who all live in New York City, and his mother, of Brookline, Mass., Mr. Bernstein is survived by a sister, Shirley Bernstein of New York City, and a brother, Burton, of Bridgewater, Conn. Mr. Bernstein and his wife began a ''trial separation'' after 25 years of marriage. They continued, however, to appear together in concerts, one such occasion being a program in tribute to Alice Tully at Alice Tully Hall, where Mr. Bernstein conducted Sir William Walton's ''Facade'' with his wife as one of the two narrators. Mrs. Bernstein died in 1978 after a long illness.

During Mr. Bernstein's Philharmonic decade, the orchestra engaged its first black member, the violinist Sanford Allen.

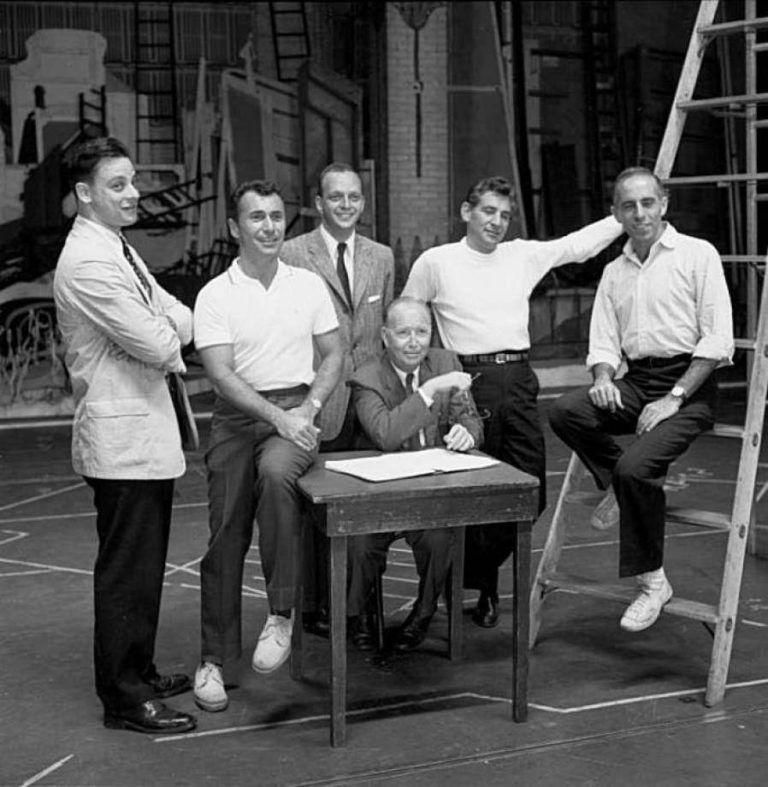

But Broadway had changed by the time Mr. Bernstein's final theatrical score reached the Mark Hellinger Theater in March 1976. The long-awaited work that he and Alan Jay Lerner had composed, ''1600 Pennsylvania Avenue,'' closed after seven performances.

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson