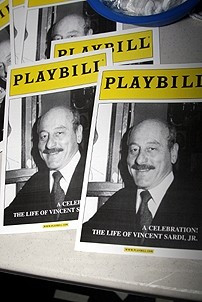

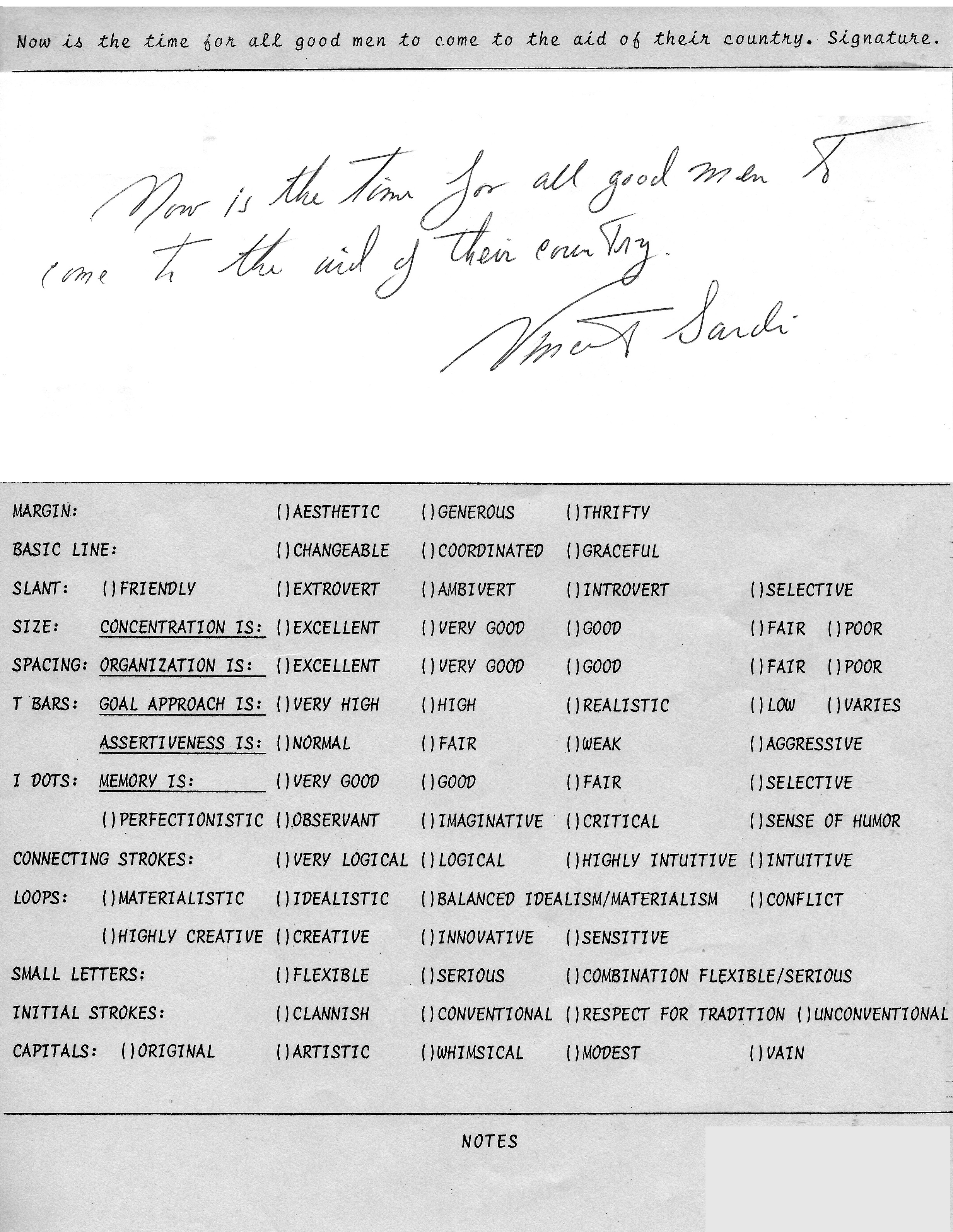

Vincent Sardi Jr., who owned and managed Sardi’s restaurant, his father’s theater-district landmark, for more than half a century and became, by wide agreement, the unofficial mayor of Broadway, died today. He was 91 and had lived in Warren, Vt., since retiring in 1997.

His death, at a hospital in Berlin, Vt., was caused by complications of a urinary tract infection, said Sean Ricketts, a grandson and manager at the restaurant.

Mr. Sardi ran one of the world’s most famous restaurants, a Broadway institution as central to the life of the theater as actors, agents and critics. It was, the press agent Richard Maney once wrote, “the club, mess hall, lounge, post office, saloon and marketplace of the people of the theater.”

Mr. Sardi understood theater people, loved them and was loved in return. He carried out-of-work actors, letting them run up a tab until their ship came in. (At one point, Sardi’s maintained 600 such accounts.)

He attended every show and made sure his head waiters did the same, so that they could recognize even bit players and make a fuss over them. At times, he exercised what he called “a fine Italian hand,” seating a hungry actor near a producer with a suitable part to cast.

He commiserated with his patrons when a show failed, and rejoiced with them when the critics were kind. He distributed favors, theater tickets and food, rode on horseback with the New York City police, and acted as a spokesman, official and unofficial, for the theater district.

Mr. Sardi was born July 23, 1915, in Manhattan and spent his early childhood in a railroad flat on West 56th Street, where his parents took in show-business boarders. In 1921, his father took over a basement restaurant in a brownstone at 246 West 44th Street. He named it the Little Restaurant, but theater people called it Sardi’s, and so it became.

The family lived upstairs. When the building was razed in 1927 to make way for the St. James Theater, Sardi’s moved to its current location, at 234 West 44th Street.

Vincent Jr., whom his father called Cino, attended Holy Cross Academy on 43rd Street. He got a taste of the theater at an early age, appearing as Pietro, an Italian urchin, in “The Master of the Inn” at the Little Theater when he was 10. The play closed quickly, but not before Vincent learned about the subtleties of the actor-director relationship. When he pointed out that an Italian would say “addio,” not “adios,” he was told to keep his opinions to himself and read the line as written.

In 1926, the Sardis moved to Flushing, Queens, where Vincent graduated from Flushing High School. He entered Columbia University intending to become a doctor but failed the chemistry examination, in part because, short of pocket money, he had sold his textbook at Barnes & Noble so that he could attend a dance. He transferred to Columbia Business School and earned a degree in 1937.

In the meantime, he began working in the family business on weekends, earning $14 a week. “My duties included stints at the cigarette counter, shifts at the cash register and a few attempts at being a Saturday headwaiter in the upstairs second-floor level,” he recalled in Playbill.

He also learned how to cater to Sardi’s unusual clientele. When Broderick Crawford was appearing in “Of Mice and Men,” Vincent was volunteered to take the actor’s Doberman for its nightly walk.

Mr. Sardi spent two years learning the food-service business at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel before rejoining Sardi’s in 1939 as dining-room captain. That year he married Carolyn Euiller. The marriage ended in divorce in 1946.

In 1946, he married Adelle Rasey, an actress. That marriage, too, ended in divorce.

In 1947, Vincent Sr. retired, and his son took over the restaurant, purchasing it from his father. Sardi’s was already renowned as a place where deals were made, gossip circulated and actors and producers made it their business to see and be seen. “The restaurant had a central place in the theater,” said Gerald Schoenfeld, the president of the Shubert Organization. “You could walk in at lunch and do a day’s business, see people you hadn’t seen in a long time. You didn’t think of going anywhere else.”

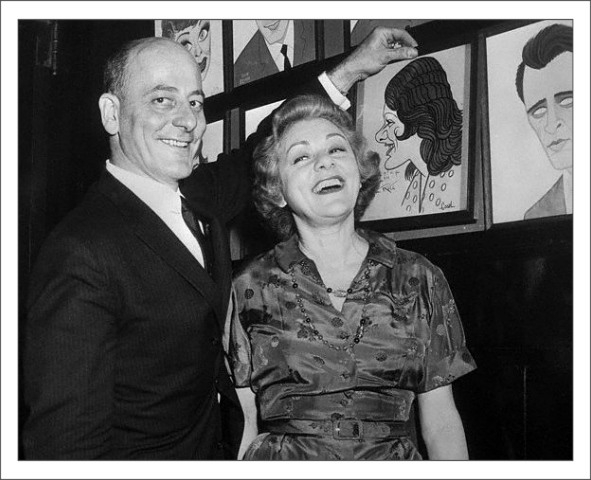

Mr. Sardi, a tall, affable man with a military bearing, perfected the art of seating enemies far apart and putting friends and potential allies near one another. “He was always the soul of politesse, but where he seated you could be crucial to making a deal,” the producer Arthur Cantor said.

Mr. Sardi also knew how to keep temperamental actors happy. “You’ve got to be awfully careful with actors out of work,” he told an interviewer. “They’re very sensitive about their fading prestige, and I know darn well they scrimp to come in here, on the chance that they’ll be considered for a part. Boosting an actor’s ego with a table in a good location is simply my way of giving him a pat on the back.”

When he was not running the restaurant, Mr. Sardi raced cars, played polo and skied. (He had recently moved to a house on Sugarbush Mountain in Vermont.) He was also president of the Greater Times Square Committee in the 1960s and the Restaurant League of New York in the 1970s.

If Sardi’s was a club, its rules were mysterious. Only Mr. Sardi knew them, in fact, and only he could explain why, for many years, one of the best tables was held for Mr. and Mrs. Ira Katzenberg. The Katzenbergs , who by the early 1950s had attended virtually every Broadway opening for 30 years, took their seats at Sardi’s at 7:15 and ordered, without fail, a brandy and a bottle of Saratoga water. The bill came to $1.62. Mr. Sardi called them his favorite customers.

“People like them keep the theater alive, and the theater is their life,” he said. “The least we can do is give them the best table in the house.”

Mr. Sardi could do nothing about the autograph hounds and the photographers who crowded around the entrance. But inside the front doors, his word was law. Diners were not to be disturbed.

Sardi’s shone brightest on the opening night of a Broadway show, and in the 1960s, a show opened nearly every night. The ritual never varied. In a line that stretched down 44th Street, theatergoers, theater folk and celebrity watchers clamored for a table, hoping against hope to be seated on the first floor, where they could see cast members, producers and the playwright of the moment entering the restaurant after the curtain rang down. As the actors made their way to their tables, the diners would stand and deliver an ovation.

Once seated, the actors, producers and playwright would put on a brave face waiting for the reviews. The first 25 copies of The New York Times and The New York Herald Tribune were rushed over to Sardi’s from the printing presses at midnight, with the review pages marked. Mr. Sardi would man the telephone, taking calls from friends of the cast, ticket brokers and newspaper columnists eager to get a read on the fate of the new play. If the reviews were poor, a pall descended over the dining room, and diners slinked out the door. If the reviews were good, it was champagne all around and a celebration until the wee hours.

“All of us on the staff were caught up in each Broadway play,” Mr. Sardi wrote in Playbill. “We became involved in the raising of money, the casting of roles, the progress of rehearsals, and, after opening night, the success or failure of a play.”

In 1946, hoping to capture some of the excitement of Sardi’s, the radio station WOR created “Luncheon at Sardi’s,” an hourlong program in which the host moved from table to table, microphone in hand, interviewing celebrities. In 1949, the show spawned a television spin-off, “Dinner at Sardi’s,” which failed to catch fire.

Undeterred, Mr. Sardi appeared as himself in two television dramas in the mid-50s, “Catch a Falling Star,” on “Robert Montgomery Presents,” and “Now, Where Was I?” a CBS production.

He also turned out a cookbook, “Curtain Up at Sardi’s” (1957), which he wrote with Helen Bryson. It included, of course, the restaurant’s signature dish, cannelloni with Sardi sauce, a homey curiosity in which French crepes were stuffed with ground chicken, ground beef, spinach and Parmesan cheese, then topped with a velouté sauce that was enhanced with Hollandaise, sherry and whipped cream.

By the late 1950’s, Sardi’s was grossing about $1 million a year.

In September 1985, Mr. Sardi sold it for $6.2 million to two producers from Detroit, Ivan Bloch and Harvey Klaris, and the restaurateur Stuart Lichtenstein.

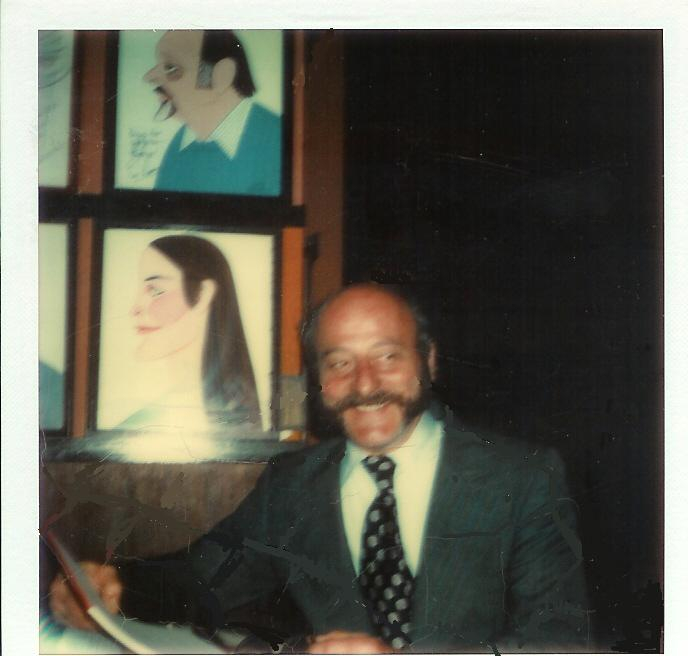

Mr. Sardi, who had planned to spend a tranquil retirement in Vermont, resumed ownership of Sardi’s in 1991. He gave it a facelift, leaving intact the 700 or so caricatures of theater people that hang on the walls. He also brought in serious chefs, who gradually improved the quality of the food, although Sardi’s, even in its heyday, never owed its reputation to its kitchen.

Mr. Sardi is survived by his wife, June Keller; a sister, Anne Gina, of Stamford, Conn.; three children, Paul, of Coco Beach, Fla., David, of San Diego, and Tabitha Sardi, of Manhattan; nine grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren. A daughter, Jennifer, died earlier.

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson  Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson