Wesaw Family History & Genealogy

Wesaw Last Name History & Origin

AddHistory

We don't have any information on the history of the Wesaw name. Have information to share?

Name Origin

We don't have any information on the origins of the Wesaw name. Have information to share?

Spellings & Pronunciations

We don't have any alternate spellings or pronunciation information on the Wesaw name. Have information to share?

Nationality & Ethnicity

We don't have any information on the nationality / ethnicity of the Wesaw name. Have information to share?

Famous People named Wesaw

Are there famous people from the Wesaw family? Share their story.

Early Wesaws

These are the earliest records we have of the Wesaw family.

Wesaw Family Members

Wesaw Family Photos

Discover Wesaw family photos shared by the community. These photos contain people and places related to the Wesaw last name.

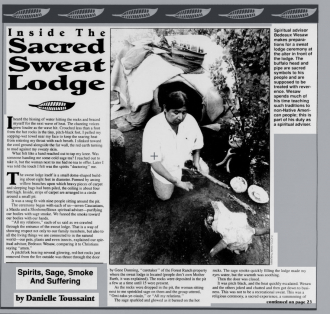

Spirits, Sage, Smoke And Suffering

by Danielle Toussaint

I heard the hissing of water hitting the rocks and braced myself for the next wave of heat. The chanting voices grew louder as the wave hit. Crouched less than a foot from the hot rocks in the tiny, pitch-black fort, I pulled my sopping-wet towel near my face to keep the searing heat from entering my throat with each breath. I slinked toward the cool ground alongside the far wall, the red earth turning to mud against my sweaty skin. What felt like a hand reached out to tap my knee. Was someone handing me some cold sage tea? I reached out to take it, but the woman next to me had no tea to offer. Later I was told the touch I felt was the spirits “doctoring” me. The sweat lodge itself is a small dome-shaped building about eight feet in diameter. Formed by arcing willow branches upon which heavy pieces of carpet and sleeping bags had been piled, the ceiling is about four feet high. Inside, strips of carpet are arranged in a circle around a small pit. It was a snug fit with nine people sitting around the pit. The ceremony began with each of us—seven Caucasians, a Maidu and a Shoshone/Sioux spiritual adviser —purifying our bodies with sage smoke. We fanned the smoke toward our bodies with our hands. “All my relations,” each of us said as we crawled through the entrance of the sweat lodge. That is a way of showing respect not only to our family members, but also to all the living things we are connected to in the natural world—our pets, plants and even insects, explained our spiritual advisor, Bedeaux Wesaw, comparing it to Christians saying “amen.” A pitchfork bearing several glowing, red-hot rocks just removed from the fire outside was thrust through the door

by Gene Dunning, “caretaker” of the Forest Ranch property where the sweat lodge is located (people don’t own Mother Earth, it was explained). The rocks were deposited in the pit a few at a time until 15 were present. As the rocks were dropped in the pit, the woman sitting next to me sprinkled sage on them and the group uttered, “Omi-taku-ye-oiasin,” or “All my relations.” The sage sparkled and glowed as it burned on the hot

rocks. The sage smoke quickly filling the lodge made my eyes water, but the warmth was soothing. Then the door was closed. It was pitch black, and the heat quickly escalated. Wesaw and the others joked and chatted and then got down to business. This was not to be a recreational sweat. This was a religious ceremony, a sacred experience, a summoning of

the spirits to answer our prayers. The heat continued to rise, and within moments my body was drenched with sweat. We began round one with a song and both oral and silent prayers. We prayed to Tunkashila, the creator. We prayed for each other’s health and the health of our loved ones, for guidance in our lives, for help with family problems—whatever the people in the lodge wanted to pray for. “Oh. Ohhhh. Omi-taku-ye-oiasin,” the participants exclaimed after particularly noteworthy or moving prayers were uttered, or when more water was poured on the rocks. It remained pitch black this whole time. We passed around cups of sage tea and water during the ceremony, but the two other women did not drink the water. That’s because they were preparing to “go on the hill” this week for a four-day, three-night fast in which they would not be allowed food or liquids. After a spell, the door was opened and a little fresh air was let in. It became a little cooler then, but not much. After this brief respite, we started round two. How many rounds would we do? I wondered, recalling Wesaw’s earlier statements that he disliked others’ ideas about putting specific time limits on the sweat ceremony. People should not time their prayer ceremonies, he’d said. The door was shut, and the sweat began to pour out of my body once again. We said more prayers and sang more songs. I didn’t know the songs but found that trying to sing along was a good distraction from the heat. Sitting there trying to follow the songs, I tried to imagine what the neighbors, who include a Baptist minister, thought about the sounds emanating from this unusual structure. “Ohhhh. Omi-taku-ye-oiasin,” the group exclaimed as more cold water was thrown at our bodies and then on the rocks. I began taking short, panting breaths and slinking toward the ground when the heat became really intense. Then I was “doctored.” It felt like a hand touching me; I was told this meant the spirits were acknowledging my prayers. After Wesaw blew his eagle

whistle, the sound of flapping bird’s wings filled the lodge. The fluttering created wind that fanned the hot air. I felt the feathers against my skin. This, too, was attributed by participants to the presence of spirits—the eagle spirit. After the second round, the door to the lodge was opened again for another break. Then 13 more rocks were brought in.

The third round was the hottest yet. I slouched toward the ground, hair plastered to my back and hot, wet T-shirt and shorts clinging to my skin. “It’s all in your mind,” Wesaw had told me when I had commented during a break about the intensity of the heat. So I resigned myself to my fate and tried to stop thinking about how nice the fresh air was going to feel and taste. The heat, the darkness and the songs combined at one point to create a strange and difficult-to-describe feeling—an elated, peaceful feeling. Mostly, though, the lack of oxygen was uncomfortable. People were panting and squirming around me; I wasn’t the only one suffering. Our suffering, however, was temporary. Other people in our world are suffering far worse, Wesaw told us. Images of someone lying in bed dying of cancer or AIDS or of a Kurdish mother holding a stiff, dead infant came to my mind. I sat up and faced the ring of rocks to pray.

During one round, Wesaw’s pipe was passed from person to person. Wesaw, as a pipe holder, has an esteemed position. The pipe is sacred to him. After four rounds and more than two hours of sweating, most of us emerged from the lodge. Wesaw and one of the women preparing for her fast remained for another round. I felt shaky, disoriented and a little lightheaded as the cool mountain air hit my wet body. I passed by the altar decorated with fabric-wrapped bits of tobacco, a buffalo skull and an upright branch from which eagle feathers hung and stood, a little dazed and barefoot, under the trees. It certainly had not been a typical Friday night. Sweat lodge ceremonies are enjoying a resurgence of interest, particularly among “new age” and crystaladmiring types. As a result, some native people have begun charging for admittance to sweat lodge ceremonies. Wesaw finds that practice abhorrent. “Our religion is not for sale,” he said. Wesaw sees it as his duty to provide spiritual advice and sweat ceremonies to anyone who wants and needs this, regardless of their religious or ethnic background. According to Wesaw, some of the new-age people are performing sweat lodge ceremonies improperly, and that bothers him. Those who abuse the ceremony are asking for trouble, he said. Philosophies about how to “correctly” perform a sweat lodge ceremony vary widely. Yet most adherents to the ceremony believe those who partake become purified during the sweat bath, their wrongs melting away. Their prayers can be answered. The ceremony sometimes is compared to the Christian confession. In some tribes, women traditionally were not allowed to share sweat ceremonies with the men. Some native people still are troubled by women entering sweat lodges. Most of the native people leading such ceremonies have no problem integrating it, though taboos about allowing menstruating women in the sweat lodge remain.

The sage sparkled and glowed as it burned on the hot rocks. The sage smoke quickly filling the lodge made my eyes water, but the warmth was soothing.

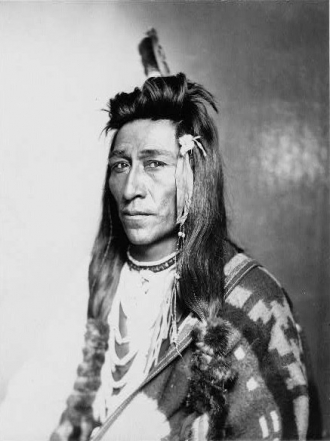

p HOTQ/MARK THAIMAN

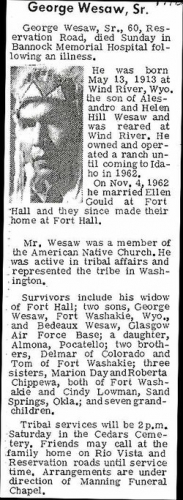

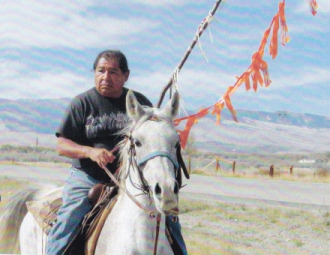

Spiritual advisor Bedeaux Wesaw makes preparations for a sweat lodge ceremony at the alter in front of the lodge. The buffalo head and pipe are sacred symbols to his people and are supposed to be treated with reverence. Wesaw spends much of his time teaching such traditions to non-Native American people; this is part of his duty as a spiritual adviser.

Wesaw Family Tree

Discover the most common names, oldest records and life expectancy of people with the last name Wesaw.

Updated Wesaw Biographies

Popular Wesaw Biographies

Wesaw Death Records & Life Expectancy

The average age of a Wesaw family member is 54.0 years old according to our database of 70 people with the last name Wesaw that have a birth and death date listed.

Life Expectancy

Oldest Wesaws

These are the longest-lived members of the Wesaw family on AncientFaces.

Other Wesaw Records

Share memories about your Wesaw family

Leave comments and ask questions related to the Wesaw family.

Followers & Sources