Advertisement

Advertisement

Richard Wozniak

About me:

I haven't shared any details about myself.

About my family:

I haven't shared details about my family.

Interested in the last names:

I'm not following any families.

Updated: May 6, 2025

Message Richard Wozniak

Loading...one moment please

Recent Activity

Richard Wozniak

updated main photo

May 08, 2025 8:29 PM

biography

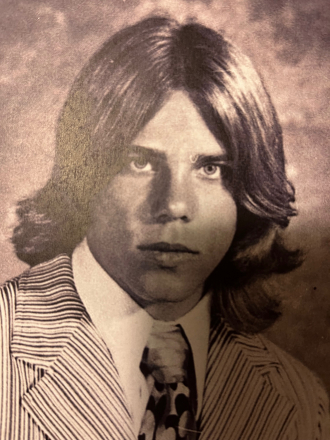

Steven E Stawnychy

Steven E Stawnychy

Richard Wozniak

updated a bio

May 06, 2025 9:56 PM

Richard Wozniak

updated a photo

May 06, 2025 9:50 PM

Richard Wozniak

tagged a photo

May 06, 2025 9:49 PM

Richard Wozniak

shared a photo

May 06, 2025 9:49 PM

Steven E Stawnychy

Steven E Stawnychy High School Year Book Photo...

Steven E Stawnychy High School Year Book Photo...

Photos Added

Recent Comments

Richard hasn't made any comments yet

Richard's Followers

Be the first to follow Richard Wozniak and you'll be updated when they share memories. Click the to follow Richard.

Favorites

Loading...one moment please