Barbara Love, Who Fought for Lesbians to Have a Voice, Dies at 85

As an activist and an author, she was determined to demystify and normalize the lesbian experience, and to integrate it into the women’s movement.

By Penelope Green

Published Dec. 1, 2022 and Updated Dec. 2, 2022, 4:39 p.m. ET

Barbara Love, a feminist activist who fought for gay rights and for lesbians to have a place — and a voice — in the women’s movement in its early days, died on Nov. 13 in the Bronx. She was 85.

The cause was complications of leukemia and Parkinson’s disease, said her wife, Donna Smith.

Raised in privilege in New Jersey, Ms. Love came of age in the late 1950s and early ’60s as a closeted young woman in Greenwich Village who haunted the city’s Mafia-run lesbian bars, which were often raided by the police. (A blinking red light signaled their arrival, after which women were forbidden to dance or touch lest they be arrested.)

“We’re like cockroaches,” she said of her fellow lesbians of the era. “We only come out at night.”

A girlfriend asked Ms. Love to de-emphasize her feminine looks by cutting her hair and dressing mannishly. One evening their car broke down, and a group of male thugs who had stopped to help, seeing her masculine appearance, beat her bloody. In those pre-Stonewall days, you could be fired if your employer discovered you were gay. Your parents might no longer welcome you home. Until 1973, the American Psychiatric Association considered homosexuality a mental illness.

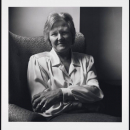

Image

Ms. Love, in glasses, walking just behind a large banner that says “Gay Community Celebration of Love and Life,” with a group of marchers.

Ms. Love, behind the banner and wearing glasses, at a candlelight march in Greenwich Village on Christmas Eve 1970 in recognition that many gay people wouldn’t be welcome at their families’ homes for the holidays. Credit...Diana Jo Davies, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library

Ms. Love, in glasses, walking just behind a large banner that says “Gay Community Celebration of Love and Life,” with a group of marchers.

But New York City was also a fertile landscape for the newly- empowered gay rights movement and the women’s movement, and for the many consciousness-raising groups that contributed to both.

With her friend Kate Millett, the academic, artist and activist who would go on to write the feminist blockbuster “Sexual Politics,” Ms. Love participated in street theater, like the Colgate Dump-In, at which activists poured Colgate-Palmolive products into a toilet that they’d set up at the company’s headquarters on Park Avenue to protest its treatment of women on the assembly line. They also staged a demonstration in front of The New York Times’s classified advertising office to protest gender segregation in the paper’s “Help Wanted” ads; The Times soon changed that practice.

Ms. Love was among a group of lesbians who fought to be recognized by the National Organization for Women, a battle that was emblematic of the fractious early years of the women’s movement, which was often seen as too white and too straight. NOW’s president, Betty Friedan — the author of “The Feminine Mystique,” a touchstone of the movement — had derided lesbian feminists as “the Lavender Menace,” seemingly internalizing the bias of the mainstream press and popular culture by seeing the concerns of lesbians as a threat to the political aims of the movement.

So Ms. Love, the author Rita Mae Brown and others who had formed a consciousness-raising group of lesbian feminists took action. They made T-shirts with the phrase “The Lavender Menace” and wore them to NOW’s Second Congress to Unite Women, a meeting held in the spring of 1970 in New York City. They hid the shirts under their coats before switching the lights off and on and striding through the audience, coats off, holding placards declaring, “We are your worst nightmare, your best fantasy.” The group won over many of the attendees with their prank.

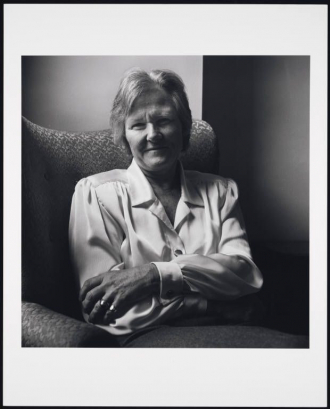

Image

Ms. Love in glasses, wearing a turtleneck under a plaid jacket and speaking into a microphone, seated next to Sidney Abbott, who is wearing a light sweater.

Ms. Love, right, in 1973 with Sidney Abbott, her partner at the time. The two collaborated on the book “Sappho Was a Right-On Woman: A Liberated View of Lesbianism,” published in 1972.

Ms. Love in glasses, wearing a turtleneck under a plaid jacket and speaking into a microphone, seated next to Sidney Abbott, who is wearing a light sweater.

Ms. Love’s experiences, typical of so many of her generation, spurred her to write “Sappho Was a Right-On Woman: A Liberated View of Lesbianism” with Sidney Abbott, her partner at the time. The book is a compassionate exploration of lesbian life in the not-so-recent past — “a maze of pseudonyms, gay bars, arbitrary role-playing, petty and grand deception,” as Carolyn See wrote in a review for The Los Angeles Times, “shadowed by the constant fear of being fired from jobs, spurned by parents, doomed to a life of almost total isolation.”

The book serves as a contemporary account of how lesbians gained acceptance in the women’s movement: “how they have emerged — almost existentially — as women like any others,” Ms. See wrote.

Ms. Love and Ms. Abbott said they wrote the book because their ambition was to be ordinary; people, they joked, seemed to know less about lesbians than they did about Newfoundland dogs. “Our goal,” they wrote, “is to go about our lives — as human beings, as women, as Lesbians — un-self-consciously, and to be able to spend all of our energy and time on work or fun, and none on the arts of concealment or on self-hatred.”

The book was dedicated “to those who have suffered for their sexual preference, most especially to Sandy, who committed suicide, to Cam, who died of alcoholism, and to Lydia, who was murdered; and to all who are working to create a future for Lesbians.”

Barbara Joan Love was born on Feb. 27, 1937, in Ridgewood, N.J. Her father, Egon, was a prosperous Danish-born hosiery manufacturer. (Barbara wanted to join his company, but he didn’t think women were qualified to run a business.) Her mother, Lois (Ashley) Love, was a homemaker.

Barbara and her two brothers grew up in “upper-middle-class comfort,” she wrote in her 2021 memoir, “There at the Dawning: Memories of a Lesbian Feminist,” with a maid and a chauffeur, and Sunday dinners at the country club.

In her early 20s, she broke political ranks and registered as a Democrat, the first one in her family to do so for generations. In high school, she was a competitive swimmer and won state championships. She studied journalism at Syracuse University, graduating in 1959.

In 1971, Ms. Love was one of the founders of Identity House, a walk-in counseling center for gay people, at first housed in the basement of a church in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan. The experience made Ms. Love want to be therapist, and in 1975 she earned a master’s degree in psychology from the New School for Social Research, though she ultimately didn’t pursue a career in the field.

With Morty Manford, a gay activist and an assistant New York State attorney general, she was a founder of Parents of Gays, a group that evolved into PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays), an especially powerful organization during the AIDS crisis. They recognized that it wasn’t just gay people who were isolated from society; their parents suffered, too.

Ms. Love’s father had shunned her when she came out, but her mother, by then divorced from her father, had declared, “First to thine own self be true!” (She had been an actress in her youth.) She, Mr. Manford’s mother and other parents were eager to join, and at the Christopher Street Liberation Day March in 1972, they proudly walked with their children. Ms. Love’s mother carried a sign that read, “Loves Mother Loves Love.” (Mr. Manford died of AIDS in 1992 at 41.)

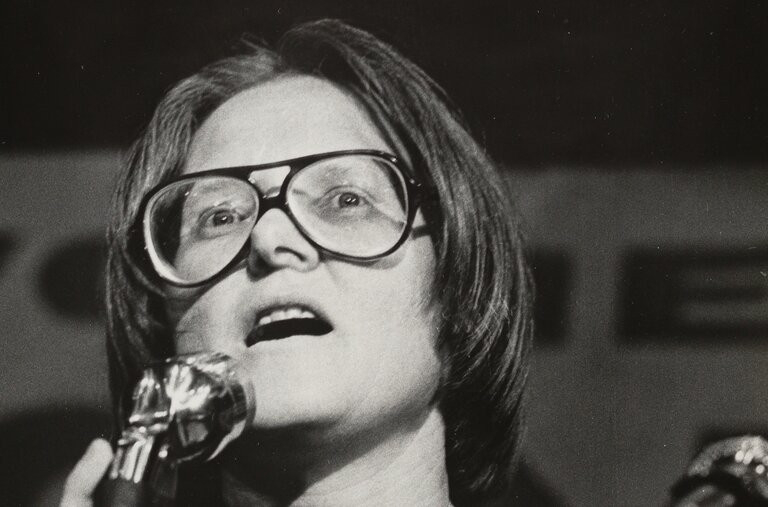

Ms. Love, in glasses and holding a sign saying “Mothers Respect Your Daughter’s Choice” alongside her mother, who has short hair and is wearing pearls, and whose sign reads “Loves Mother Loves Love.”

Ms. Love and her mother, Lois, left, at the Christopher Street Liberation Day March in 1972. Ms. Love was a co-founder of Parents of Gays, a group that later evolved into PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays). Credit...Bettye Lane

Ms. Love, in glasses and holding a sign saying “Mothers Respect Your Daughter’s Choice” alongside her mother, who has short hair and is wearing pearls, and whose sign reads “Loves Mother Loves Love.”

Ms. Love had a long career as an editor at trade publications, from an early job with The New York Lumber Trade Journal to Supermarketing and Folio, which covered the magazine industry. For a few years in the late 1960s, she worked as a censor at CBS, making sure that no miniskirts appeared on the network’s soap operas and that if a script called for a man to be in a single woman’s apartment at night, he had to be shown leaving it. The producers, she recalled, called her “the Black Death.”

She was the editor of “Feminists Who Changed America, 1963-1975” (2006), a Who’s Who of the movement containing the biographies of more than 2,000 women. A collaborative project, it was nearly a decade in the making.

In addition to her wife, whom she married in 2018 — David N. Dinkins, the former mayor of New York, was the officiant — she is survived by her brother, Anthony, and her stepsister, Ellamae Cobb. She lived in Manhattan.

“Barbara was a within-the-system hard-working feminist,” Phyllis Chesler, the feminist activist, psychologist and author, said in an email. “Barbara came from a wealthy, Republican family, and was a competitive athlete, and thus, although she was ‘different,’ always carried herself with great confidence.”

In her memoir, Ms. Love wrote of coming out to her father and brothers in 1970, when she was 33. It was Christmas Eve, and she helped organize an event, recognizing that many gay people wouldn’t be welcome in their homes for the holidays. They carried candles and marched through Greenwich Village singing “Silent Night.” When it was over, Ms. Love drove to her father’s home in New Jersey.

“Why weren’t you here? You missed everything. And why are you covered with wax?” her older brother challenged her.

When she told him, and revealed she was gay, he said: “You have to get off that ship. That ship is sinking.”

She replied, “Douglas, I am that ship.”

A correction was made on Dec. 2, 2022

An earlier version of this obituary omitted the name of a survivor. In addition to her wife and her brother, Ms. Love is survived by a stepsister, Ellamae Cobb.

Penelope Green is a reporter on the Obituaries desk and a feature writer for the Style and Real Estate sections. She has been a reporter for the Home section, editor of Styles of The Times, an early iteration of Style, and a story editor at The Times Magazine. @greenpnyt • Facebook

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson