Bobby Short, Icon of Manhattan Song and Style, Dies at 80

March 21, 2005

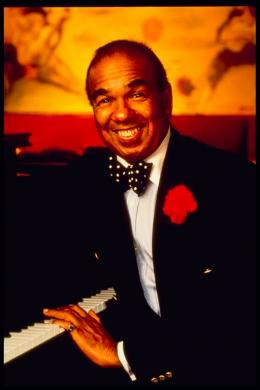

Bobby Short, the cherubic singer and pianist whose high-spirited but probing renditions of popular standards evoked the glamour and sophistication of Manhattan nightlife, died yesterday at New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

He was 80, and had homes in Manhattan and southern France.

The cause was leukemia, said his press agent, Virginia Wicks.

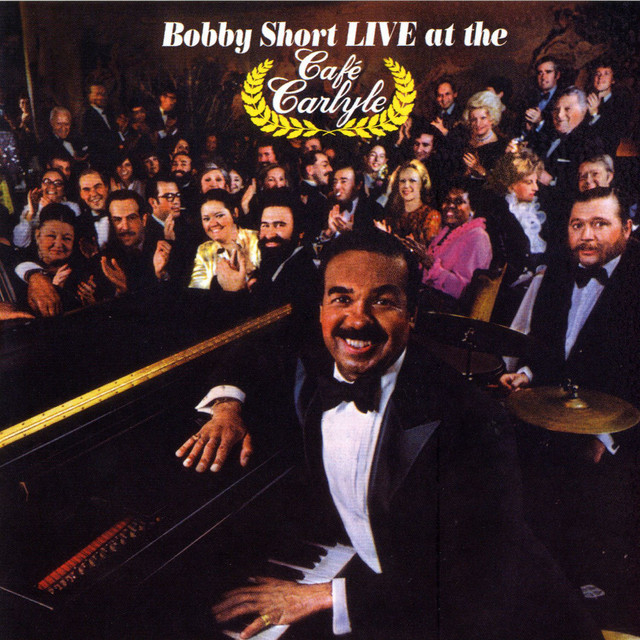

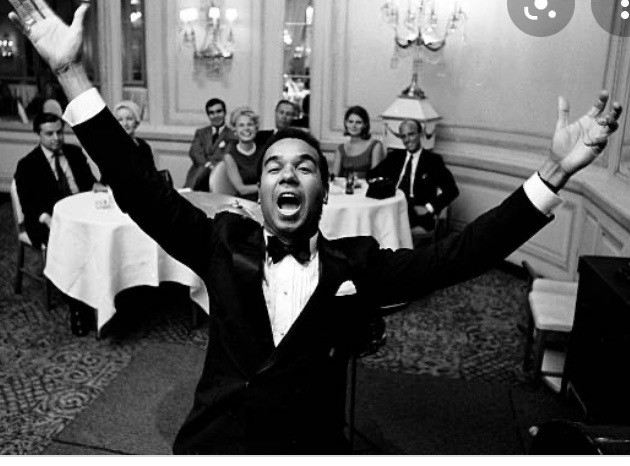

Mr. Short liked to call himself a saloon singer, and his "saloon" since 1968 was one of the most elegant in the country, the intimate Cafe Carlyle tucked in the Carlyle hotel on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. There for six months each year, in a room where he was only a few feet from his audience, he sang and accompanied himself on the piano. Although he had said that last year's engagement would be his last, he reversed himself in June and extended for 2005, the 50th anniversary of the club.

Over the years, Mr. Short transcended the role of cabaret entertainer to become a New York institution and a symbol of civilized Manhattan culture. In Woody Allen's films a visit to the Carlyle became an essential stop on his characters' cultural tour. He attracted a chic international clientele that included royalty, movie stars, sports figures, captains of industry, socialites and jazz aficionados and was a guest and performer at the White House when President and Mrs. Richard M. Nixon entertained the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. He also appeared in small roles in a number of television commercials and movies.

Mr. Short's social status sometimes overshadowed his significance as a jazz pianist, singer and scholar. He dedicated himself to spreading an awareness of the African-American contribution to New York's musical theater. In his pantheon of great American songwriters, Cole Porter stood side by side with Duke Ellington, Eubie Blake, Fats Waller, and Waller's sometime lyricist Andy Razaf, who wrote the words for "Guess Who's in Town?," Mr. Short's unofficial musical greeting.

He was an accomplished, aggressive stride pianist who in his later years at the Cafe Carlyle expanded his musical forces to lead a swing band. A typical performance blended uptown and downtown styles in a heady mix.

Although Whitney Balliett, in a 1970 New Yorker profile, characterized Mr. Short's act and his voice as "stripped to its essentials - words lifted and carried by the curves of melody," the profile also noted that his baritone, frequently plagued by laryngitis, "lends his voice a searching down sound, and his uncertain notes enhance the cheerfulness and abandon he projects."

Mr. Short talked about his life in two books: a memoir, "Black and White Baby" (Dodd, Mead; 1971), and "Bobby Short: The Life and Times of a Saloon Singer," with Robert Mackintosh (Panache Press/Clarkson Potter, 1995) .

In the first, he described his life as one of 10 children in a family of modest means in the Depression. He began performing as a child in Danville, Ill., and recalled that by the time he was 9, he was playing the piano in a roadhouse as well as living in the traditional world of family, church and school.

"It was all right with my mother because I was in the care of a man whose aunt was a church friend of hers," he wrote. On weekend nights, if he had no other engagement, a family friend would take him from tavern to tavern where a hat was passed as he played and sang. At 10, he played and sang for a private party at the Palmer House in Chicago.

Two years later, he left home for Chicago, managed by agents who usually booked him for one-night stands at hotels. "I had no idea the image I projected," he recalled later, but he vividly remembered singing "Sophisticated Lady" in a high squeaky voice.

Sign up for the Louder Newsletter Stay on top of the latest in pop and jazz with reviews, interviews, podcasts and more from The New York Times music critics. Get it sent to your inbox.

New York came next; he still wasn't quite 13. Arrangements were made for a tutor but more thrilling were his first theatrical photographs. Equally important to Mr. Short, who was always a natty dresser and whose name often appeared on best-dressed lists, he had custom-made white tails and an almost ankle-length wraparound camel's hair coat.

After several Midtown club appearances, he was signed to appear at the Apollo Theater, where he received a tepid reception. He was told that the audience didn't care about his size or age; they were interested only in ability and familiarity with the hit songs in Harlem. His format changed and his show improved, but he ran into trouble with child labor laws. This was solved when one of his managers arranged to get the birth certificate of a 16-year-old boy who had died. The authorities were told Bobby Short was a stage name.

He returned to Danville in 1938 to continue his schooling, graduating from the Garfield School, St. Joseph's and Danville High. Still, performing was a constant. He was paid $40 a week for a full-time club job in the summer between his junior and senior year.

In "The Life and Times of a Saloon Singer," he expanded on the history of a career that began in the 1930's, but stopped short of giving readers more than a ringside table at performances. Writing in The New York Times Book Review, James Gavin pointed out that Mr. Short "has the intelligence and the perspective to have given us much more." Although a visible public presence here and in Europe, Mr. Short, the review said, failed to offer "a sparkling look into the international night life of the 50's, along with incisive cameos of the showbiz greats he knew." Mr. Gavin also chided him for not discussing his personal life.

Mr. Short had a bout of notoriety in May 1980 when Gloria Vanderbilt sued the River House on the East Side of Manhattan, which had refused to sell her a $1.1 million apartment. She accused the management of racial bias because of her friendship with him. The building's board said it wanted to avoid "unwanted publicity."

A month later, she dropped the suit. Mr. Short generally stayed out of the fray but said, "I'm old enough to be sophisticated about these things."

His only immediate survivors are a brother, Reginald Short, of Altadena, Calif., and an adopted son, Ronald Bell, of San Francisco, who was the son of Mr. Short's older brother William.

Robert Waltrip Short was born Sept. 15, 1924, the ninth of 10 children. His family was part of the great black migration that left Kentucky and points south at the turn of the century. His father, who died when Mr. Short was 9, held a number of white-collar jobs but returned to Kentucky to work in coal mines during the Depression.

In "Black and White Baby," Mr. Short recalled living as a child among many white people "on a pleasant street, in a pleasant neighborhood where the houses had front and back yards.

"I am a negro who has never lived in the South, thank God, nor was I ever trapped in an urban ghetto," he wrote.

"There was a total absence of any kind of overt prejudice in those years, and it was kept that way by our teachers - which I was not aware of then. I never expected to be treated differently than my classmates. I didn't know that colored children anywhere could be given a bad time at school."

A good deal of attention was given to music, he often said when he reminisced. There was a piano in almost every classroom and a teacher who could play it. He was drilled in sight reading and theory but basically taught himself to play and sing.

Soon after graduating from high school, he opened at the Capitol Lounge in Chicago. His act was, he said, influenced by Hildegarde who, at the time, had "the slickest night club act of all."

A year later, at 19, he worked for a week in Omaha, playing on the same bill with Nat King Cole, who remained a friend until Cole's death. He went on to Los Angeles, then Milwaukee (where he met Art Tatum, who was also performing there), and St. Louis. His friendship with Mabel Mercer began when he appeared at the Blue Angel in New York.

One of his longest engagements at the time was at the Cafe Gala in Los Angeles, which was patronized by a number of New Yorkers, including Lena Horne and Cole Porter. He remained three years, although friends and aficionados encouraged him to return to New York.

"I knew I wasn't ready for New York but I did go to Paris," he said in the 1970 New Yorker profile. He hired a maid and a French tutor, traveled to London for custom clothes and eventually returned to Los Angeles.

In 1954, he met Phil Moore, an arranger and composer who became his manager. "He figured out how my act could be enlarged, controlled and polished," he said. He made a record, and the direction of his career changed when he was flown to New York by Dorothy Kilgallen, an influential columnist of the time, to play at her husband's birthday party. He then played at several New York clubs and after brief stints in Florida and Chicago, returned to perform at Le Caprice.

He had a small part in a Cole Porter revue in Greenwich Village in 1965 and during the next few years played a number of small clubs in various cities. But, he wrote, "the night club business was not what it had been."

It was during this period in the 1960's that he began taking himself more seriously. He had become acquainted with many famous musicians, among them Leonard Bernstein and the singer Shirley Verrett, and, he said: "I decided I wanted to earn their professional respect. I knew I couldn't do it without hard work." The hard work - studying, practicing and refining - paid off. Critics began commenting on his improved singing and the long-lived engagement at the Carlyle followed.

"I felt I had a gift and I enjoyed performing," he wrote about his early years and often repeated later in his career. "I didn't know then and I don't know now how well or how badly I sing and play the piano but I knew that I was a good performer."

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson