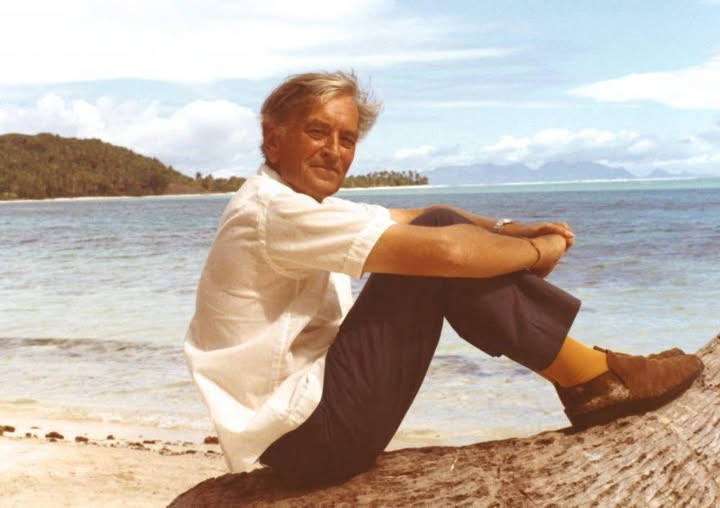

David Lean, Film Director, Dies at 83

By Peter B. Flint

April 17, 1991

David Lean, Film Director, Dies at 83

Credit...The New York Times Archives

Sir David Lean, the leading British director of both intimate films like "Brief Encounter" and "Great Expectations" and epics like "Bridge on the River Kwai" and "Lawrence of Arabia," died yesterday at his home in London. He was 83 years old.

His death was announced in London by his lawyer, Tony Reeves, who declined to disclose the cause. Stephen M. Silverman, a biographer of the filmmaker, said in New York he had died of pneumonia.

Lean's films won 28 Academy Awards, including seven each for "Bridge on the River Kwai" (1957) and "Lawrence of Arabia" (1962). He received the best-director Oscars for "River Kwai" and "Lawrence," and both films also won the Academy Award as best movie. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1984.

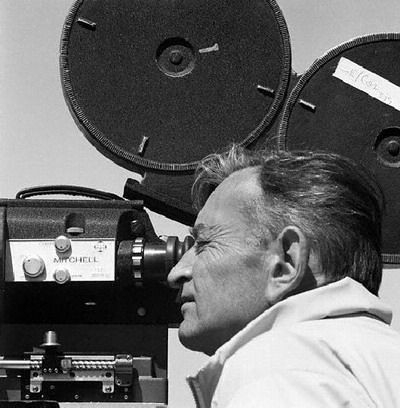

Edited Own Films

Lean was a meticulous craftsman noted for technical wizardry, subtle manipulation of emotions, superb production values, authenticity, and taste. He was one of the very few directors who edited his own films, and he also adapted or co-adapted half a dozen of them.

The filmmaker's achievements prompted Walter Kerr of The New York Times to write in 1985 that Lean was "the best British film director still active" and "he may be the best British film director ever."

The producer David Puttnam said recently he regarded Lean as "the greatest storyteller on film."

Mr. Lean repeatedly drew top performances from many top actors, including Charles Laughton, Brenda de Banzie and John Mills in the 1954 comedy "Hobson's Choice"; Katharine Hepburn as an American spinster in Venice in the 1955 comedy-drama "Summertime"; Alec Guinness as a tenacious British officer in "The Bridge on the River Kwai," and Peter O'Toole in the title role in "Lawrence of Arabia." On Directing

Of his approach to performers, Mr. Lean remarked, "Most of the time, directing actors is a matter of gentle suppression and gentle encouragement."

Omar Sharif, who portrayed a sheik in "Lawrence of Arabia" and the title role in "Dr. Zhivago," said of him: "He is ruthless, dedicated and selfish. But he has not a trace of self-indulgence."

Through the decades, he maintained autocratic control over movie sets. "Can you think of any art that isn't one person's vision?" he asked in 1984. "Making a movie is using a vast piece of machinery like a crane to draw a fine line. One person must control the machinery."

He deplored critics who habitually expressed "helpless admiration at directorial stuff that isn't difficult to do -- the show-off stuff." He added, "It's always been important to me to hide the technique."

Praise From Hepburn

In 1989, Katharine Hepburn hailed him for his perfection, saying, "David is sweet -- simple and straight -- and strong and savage, and he is the best movie director in the world."

The actress, who made "Summertime" with him in Venice in 1954, offered the tribute in an introduction to Stephen M. Silverman's biographical "David Lean," published by Harry N. Abrams.

Miss Hepburn wrote: "To work with someone who really knows what he is doing -- who has an enthusiasm for working in film beyond one's imagination -- whose capacity for work has no end -- whose determination is to produce the best possible result -- to whom nothing matters -- discomfort, exhaustion -- so long as it contributes to a perfect result. My admiration for David is infinite."

From 1942 to 1955, Mr. Lean made 11 movies, including the acclaimed "In Which We Serve" (co-directed with Noel Coward), "This Happy Breed," "Oliver Twist," "Breaking Through the Sound Barrier," "Hobson's Choice" and "Summertime."

His early movies were intimate dramas, but beginning with "River Kwai" in 1957, he made long, sumptuous, extravagant epics that took years to complete.

Some of his later movies were criticized as overlong and ostentatious, although reviewers praised individual scenes as vigorous and exciting. Some critics said he was beginning to stress form over content and visual effects over literary quality to the point that his films were becoming more stately than entertaining.

"Ryan's Daughter," a 1970 movie starring Sarah Miles about an adulterous affair on the western coast of Ireland, received the sharpest criticism. Vincent Canby of The New York Times deplored what he termed its "vacuous 19th-century Romanticism" and "calculated prettiness," adding that "this kind of extravagant filmmaking is often lovely to look at, but it becomes, toward the third hour, as boring as a cloud- watching."

Lean's later movies made him, according to Variety, the top directorial grosser of that time. Nonetheless, it took him 13 years to put together the financing for his next movie, his 16th, "A Passage to India," which vindicated his talent.

He adapted the script from E. M. Forster's 1924 novel about the traumatic clash of the British and Indian cultures. Mr. Canby hailed the 1984 film as "by far his best work" since "The Bridge on the River Kwai" and "Lawrence of Arabia" and perhaps his most humane and moving film since "Brief Encounter."

"Though vast in physical scale and set against a tumultuous Indian background, it is also intimate, funny, and moving in the manner of a filmmaker completely in control of his material," Mr. Canby wrote.

"A Passage to India" received three of the four top awards, including Best Picture, from the New York Film Critics Circle. The group named Lean the best director and Dame Peggy Ashcroft the best actress for her portrayal of the saintly Mrs. Moore.

The film earned 11 Academy Award nominations but was eclipsed by Milos Forman's "Amadeus" and won only two Oscars -- for music and Dame Peggy as best supporting actress.

However, it restored Lean to both critical and popular favor and, a year ago, he won the American Film Institute's 18th annual Life Achievement Award.

Late last year, he married for the sixth time, to Sandra Cooke, an interior designer. At the time, he was also working intensively on a major project, a $46 million screen version of Joseph Conrad's 1904 novel "Nostromo," a dark tale of greed, ambition and revolution in 19th-century South America.

However, he fell ill with what press reports said was throat cancer. He was flown home from a location in the south of France for treatment.

A tall, trim man with angular features, keen eyes, and a booming voice, Lean made films with furious concentration. He called movie making "a terrific thrill, a kick" and said the hardest element of it was "finding a story to fall in love with." An associate remarked, "David only lives, really lives when he is making a picture."

Raised a Quaker

The director who loved to make movies was not allowed to see them during his boyhood in the London suburb of Croydon, where he was born on March 25, 1908. His father, Francis, an accountant, and his mother, the former Helena Tangye, were Quakers who regarded motion pictures as sinful. But they sent him to a Quaker boarding school, Leighton Park, in Reading, where he began spending all his spare time going to the movies, captivated by what he later called "the pure audacity of the American cinema."

He was an indifferent student and left school to be an apprentice in his father's office. But after a year of boredom, he won a job at the Gaumont Studios in 1927 at the start of the sound era and worked successively as a tea boy, number-board holder, messenger, and camera assistant.

He became fascinated with film editing, learned the craft quickly, and began editing newsreels in 1930 and feature films in 1934. He soon became one of Britain's ablest and highest-paid editors. His credits as an editor included such films as "Pygmalion" (1938), "Major Barbara" (1941), and "49th Parallel" (1941). He regarded editing as the ultimate art and edited every film he directed.

By the early 1940's Lean had a reputation as the most knowledgeable technician in British films, and Noel Coward asked him to co-direct and edit "In Which We Serve," a stirring wartime tribute to the Royal Navy that the New York film critics and the National Board of Review voted as the best film of 1942.

He then co-adapted and directed three other Noel Coward works, "This Happy Breed," an affecting 1944 tribute to Britain's lower middle-class; "Blithe Spirit," a whimsical 1945 spoof of spiritualism, and "Brief Encounter," a poignant 1945 romance with compelling performances by Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard.

Mr. Lean next undertook film versions of two Charles Dickens novels, "Great Expectations" (1946), which Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called "a perfect motion picture," and "Oliver Twist" (1948), which Mr. Crowther termed "a superb piece of motion picture art." "Oliver Twist" included a performance by Alec Guinness as Fagin that was criticized by some people as anti-Semitic, but Mr. Crowther called the performance "vastly clever."

The inspiration for "Breaking Through the Sound Barrier" was a newspaper account of a jet plane that disintegrated in flight, apparently when it exceeded the speed of sound. Intrigued by supersonic flight, Mr. Lean visited aircraft factories and interviewed test pilots, designers and scientists for three months. He wrote a 20,000-word article on the subject and submitted it to Terence Rattigan, who adapted it into a 1952 screenplay.

Lean's artistry was again confirmed two years ago with screenings in Manhattan's Ziegfeld Theater of a restored "Lawrence of Arabia." The restoration, supervised by archivist Robert A. Harris, lengthened the nearly four-hour epic by about 20 minutes.

Lean, who said the film had been improperly shortened without his consent only a few days after its initial release, expressed pleasure with the restoration, remarking: "What can you do? You're cooked. Mercifully, age clouds one's anger."

His primary leisure pursuit was photography.

Sir David was married six times, and two of his former wives were actresses with whom he worked, Kay Walsh and Ann Todd.

Survivors include his wife, Sandra, and a son, Peter, by a previous marriage. Films That Won 28 Oscars

David Lean's directorial credits embrace intimate dramas as well as sweeping historical spectacles. Here are some of his major films, and the years they opened in London. In Which We Serve (with Noel Coward) (1942) This Happy Breed (1944) Brief Encounter (1945) Great Expectations (1946) Oliver Twist (1948) Breaking Through the Sound Barrier (1952) Hobson's Choice (1954) Summertime (1955) Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) Lawrence of Arabia (1962) Dr. Zhivago (1965) Ryan's Daughter (1970) A Passage to India (1984)

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson