In 1932, Capra decided to make a motion picture that reflected the social conditions of the day. He and Riskin wrote the screenplay for American Madness (1932), a melodrama that is an important precursor to later Capra films, not only with It's a Wonderful Life (1946) which shares the plot device of a bank run, but also in the depiction of the irrationality of a crowd mentality and the ability of the individual to make a difference. In the movie, an idealistic banker is excoriated by his conservative board of directors for making loans to small businesses on the basis of character rather than on sounder financial criteria. Since the Great Depression is on, and many people lack collateral, it would be impossible to productively lend money on any other criteria than character, the banker argues. When there is a run on the bank due to a scandal, it appears that the board of directors are rights the bank depositors make a run on the bank to take out their money before the bank fails. The fear of a bank failure ensures that the failure will become a reality as a crowd mentality takes over among the clientèle. The board of directors refuse to pledge their capital to stave off the collapse of the bank, but the banker makes a plea to the crowd, and just like George Bailey's depositors in It's a Wonderful Life (1946), the bank is saved as the fears of the crowd are ameliorated and businessmen grateful to the banker pledge their capital to save the bank. The board of directors, impressed by the banker's character and his belief in the character of his individual clients (as opposed to the irrationality of the crowd), pledge their capital and the bank run is staved off and the bank is saved.

In his biography, "The Name Above the Picture," Capra wrote that before American Madness (1932), he had only made "escapist" pictures with no basis in reality. He recounts how Poverty Row studios, lacking stars and production values, had to resort to "gimmick" movies to pull the crowds in, making films on au courant controversial subjects that were equivalent to "yellow journalism."

What was more important than the subject and its handling was the maturation of Capra's directorial style with the film. Capra had become convinced that the mass-experience of watching a motion picture with an audience had the psychological effect in individual audience members of slowing down the pace of a film. A film that during shooting and then when viewed on a movieola editing device and on a small screen in a screening room among a few professionals that had seemed normally paced became sluggish when projected on the big screen. While this could have been the result of the projection process blowing up the actors to such large proportions, Capra ultimately believed it was the effect of mass psychology affecting crowds since he also noticed this "slowing down" phenomenon at ball games and at political conventions. Since American Madness (1932) dealt with crowds, he feared that the effect would be magnified.

He decided to boost the pace of the film, during the shooting. He did away with characters' entrances and exits that were a common part of cinematic "grammar" in the early 1930s, a survival of the "photoplays" days. Instead, he "jumped" characters in and out of scenes, and jettisoned the dissolves that were also part of cinematic grammar that typically ended scenes and indicated changes in time or locale so as not to make cutting between scenes seem choppy to the audience. Dialogue was deliberately overlapped, a radical innovation in the early talkies, when actors were instructed to let the other actor finish his or her lines completely before taking up their cue and beginning their own lines, in order to facilitate the editing of the sound-track. What he felt was his greatest innovation was to boost the pacing of the acting in the film by a third by making a scene that would normally play in one minute take only 40 seconds. When all these innovations were combined in his final cut, it made the movie seem normally paced on the big screen, though while shooting individual scenes, the pacing had seemed exaggerated. It also gave the film a sense of urgency that befitted the subject of a financial panic and a run on a bank. More importantly, it "kept audience attention riveted to the screen," as he said in his autobiography. Except for "mood pieces," Capra subsequently used these techniques in all his films, and he was amused by critics who commented on the "naturalness" of his direction.

Capra was close to completely establishing his themes and style. Justly accused of indulging in sentiment which some critics labeled "Capra-corn," Capra's next film, Lady for a Day (1933) was an adaptation of Damon Runyon's 1929 short story "Madame La Gimp" about a nearly destitute apple peddler whom the superstitious gambler Dave the Dude (portrayed by Warner Brothers star Warren William) sets up in high style so she and her daughter, who is visiting with her finance, will not be embarrassed. Dave the Dude believes his luck at gambling comes from his ritualistically buying an apple a day from Annie, who is distraught and considering suicide to avoid the shame of her daughter seeing her reduced to living on the street. The Dude and his criminal confederates put Annie up in a luxury apartment with a faux husband in order to establish Annie in the eyes of her daughter as a dignified and respectable woman, but in typical Runyon fashion, Annie becomes more than a fake as the masquerade continues.

Robert Riskin wrote the first four drafts of Lady for a Day (1933), and of all the scripts he worked on for Capra, the film deviates less from the script than any other. After seeing the movie, Runyon sent a telegraph to Riskin praising him for his success at elaborating on the story and fleshing out the characters while maintain his basic story. Lady for a Day (1933) was the favorite Capra film of John Ford, the great filmmaker who once directed the unknown extra. The movie cost $300,000 and was the first of Capra's oeuvre to attract the attention of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, getting a Best Director nomination for Capra, plus nods for Riskin and Best Actress. The movie received Columbia's first Best Picture nomination, the studio never having attracted any attention from the Academy before Lady for a Day (1933). (Capra's last film was the flop remake of Lady for a Day (1933) with Bette Davis and Glenn Ford, Pocketful of Miracles (1961))

Capra reunited with Stanwyck and produced his first universally acknowledged classic, The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1932), a film that now seems to belong more to the oeuvre of Josef von Sternberg than it does to Frank Capra. With "General Yen," Capra had consciously set out to make a movie that would win Academy Awards. Frustrated that the innovative, timely, and critically well-received American Madness (1932) had not received any recognition at the Oscars (particularly in the director's category in recognition of his innovations in pacing), he vented his displeasure to Columbia boss Cohn. "Forget it," Cohn told Capra, as recounted in his autobiography. "You ain't got a Chinaman's chance. They only vote for that arty junk."

Capra set out to boost his chances by making an arty film featuring a "Chinaman" that confronted that major taboo of American cinema of the first half of the century, miscegenation. In the movie, the American missionary Megan Davis is in China to marry another missionary. Abducted by the Chinese Warlord General Yen, she is torn away from the American compound that kept her isolated from the Chinese and finds herself in a strange, dangerous culture. The two fall in love despite their different races and life-views. The film ran up against the taboo against miscegenation embedded in the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association's Production Code, and while Megan merely kisses General Yen's hand in the picture, the fact that she was undeniably in love with a man from a different race attracted the vituperation of many bigots. Having fallen for Megan, General Yen engenders her escape back to the Americans before willingly drinking a poisoned cup of tea, his involvement with her having cost him his army, his wealth, and now his desire to live. The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1932) marks the introduction of suicide as a Capra theme that will come back repeatedly, most especially in George Bailey's breakdown on the snowy bridge in It's a Wonderful Life (1946). Despair often shows itself in Capra films, and although in his post-"General Yen" work, the final reel wraps things up in a happy way, until that final reel, there is tragedy, cynicism, heartless exploitation, and other grim subject matter that Capra's audiences must have known were the truth of the world, but that were too grim to face when walking out of a movie theater. When pre-Code movies were rediscovered and showcased across the United States in the 1990s, they were often accompanied by thesis about how contemporary audiences "read" the films (and post-1934 more Puritanical works), as the movies were not so frank or racy as supposed. There was a great deal of signaling going on which the audience could read into, and the same must have been true for Capra's films, giving lie to the fact that he was a sentimentalist with a saccharine view of America. There are few films as bitter as those of Frank Capra before the final reel.

Despair was what befell Frank Capra, personally, on the night of March 16, 1934, which he attended as one of the Best Director nominees for Lady for a Day (1933). Capra had caught Oscar fever, and in his own words, "In the interim between the nominations and the final voting...my mind was on those Oscars." When Oscar host Will Rogers opened the envelope for Best Director, he commented, "Well, well, well. What do you know. I've watched this young man for a long time. Saw him come up from the bottom, and I mean the bottom. It couldn't have happened to a nicer guy. Come on up and get it, Frank!"

Capra got up to go get it, squeezing past tables and making his way to the open dance floor to accept his Oscar. "The spotlight searched around trying to find me. 'Over here!' I waved. Then it suddenly swept away from me -- and picked up a flustered man standing on the other side of the dance floor - Frank Lloyd!"

Frank Lloyd went up to the dais to accept HIS Oscar while a voice in back of Capra yelled, "Down in front!"

Capra's walk back to his table amidst shouts of "Sit down!" turned into the "Longest, saddest, most shattering walk in my life. I wished I could have crawled under the rug like a miserable worm. When I slumped in my chair I felt like one. All of my friends at the table were crying."

That night, after Lloyd's Cavalcade (1933), beat Lady for a Day (1933) for Best Picture, Capra got drunk at his house and passed out. "Big 'stupido,'" Capra thought to himself, "running up to get an Oscar dying with excitement, only to crawl back dying with shame. Those crummy Academy voters; to hell with their lousy awards. If ever they did vote me one, I would never, never, NEVER show up to accept it."

Capra would win his first of three Best Director Oscars the next year, and would show up to accept it. More importantly, he would become the president of the Academy in 1935 and take it out of the labor relations field a time when labor strife and the formation of the talent guilds threatened to destroy it.

The International Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences had been the brainchild of Louis B. Mayer in 1927 (it dropped the "International" soon after its formation). In order to forestall unionization by the creative talent (directors, actors and screenwriters) who were not covered by the Basic Agreement signed in 1926, Mayer had the idea of forming a company union, which is how the Academy came into being. The nascent Screen Writers Union, which had been created in 1920 in Hollywood, had never succeeded in getting a contract from the studios. It went out of existence in 1927, when labor relations between writers and studios were handled by the Academy's writers' branch.

The Academy had brokered studio-mandated pay-cuts of 10% in 1927 and 1931, and massive layoffs in 1930 and 1931. With the inauguration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt on March 4, 1933, Roosevelt took no time in attempting to tackle the Great Depression. The day after his inauguration, he declared a National Bank Holiday, which hurt the movie industry as it was heavily dependent on bank loans. Louis B. Mayer, as president of the Association of Motion Picture Producers, Inc. (the co-equal arm of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association charged with handling labor relations) huddled with a group from the Academy (the organization he created and had long been criticized for dominating, in both labor relations and during the awards season) and announced a 50% across-the-board pay cut. In response, stagehands called a strike for March 13th, which shut down every studio in Hollywood.

After another caucus between Mayer and the Academy committee, a proposal for a pay-cut on a sliding-scale up to 50% for everyone making over $50 a week; which would only last for eight weeks, was inaugurated. Screen writers resigned en masse from the Academy and joined a reformed Screen Writers Guild, but most employees had little choice and went along with it. All the studios but Warner Bros. and Sam Goldwyn honored the pledge to restore full salaries after the eight weeks, and Warners production chief Darryl F. Zanuck resigned in protest over his studio's failure to honor its pledge. A time of bad feelings persisted, and much anger was directed towards the Academy in its role as company union.

The Academy, trying to position itself as an independent arbiter, hired the accounting firm of Price Waterhouse for the first time to inspect the books of the studios. The audit revealed that all the studios were solvent, but Harry Warner refused to budge and Academy President 'Conrad Nagel' resigned, although some said he was forced out after a vote of no-confidence after arguing Warner's case. The Academy announced that the studio bosses would never again try to impose a horizontal salary cut, but the usefulness of the Academy as a company union was over.

Under Roosevelt's New Deal, the self-regulation imposed by the National Industrial Relations Act (signed into law on June 16th) to bring business sectors back to economic health was predicated upon cartelization, in which the industry itself wrote its own regulatory code. With Hollywood, it meant the re-imposition of paternalistic labor relations that the Academy had been created to wallpaper over. The last nail in the company union's coffin was when it became public knowledge that the Academy appointed a committee to investigate the continued feasibility of the industry practice of giving actors and writers long-term contracts. High salaries to directors, actors, and screen writers was compensation to the creative people for producers refusing to ceded control over creative decision-making. Long-term contracts were the only stability in the Hollywood economic set-up up creative people,. Up to 20%-25% of net earnings of the movie industry went to bonuses to studio owners, production chiefs, and senior executives at the end of each year, and this created a good deal of resentment that fueled the militancy of the SWG and led to the formation of the Screen Actors Guild in July 1933 when they, too, felt that the Academy had sold them out.

The industry code instituted a cap on the salaries of actors, directors, and writers, but not of movie executives; mandated the licensing of agents by producers; and created a reserve clause similar to baseball where studios had renewal options with talent with expired contracts, who could only move to a new studio if the studio they had last been signed to did not pick up their option.

The SWG sent a telegram to FDR in October 1933 denouncing this policy, arguing that the executives had taken millions of dollars of bonuses while running their companies into receivership and bankruptcy. The SWG denounced the continued membership of executives who had led their studios into financial failure remaining on the corporate boards and in the management of the reorganized companies, and furthermore protested their use of the NIRA to write their corrupt and failed business practices into law at the expense of the workers.

There was a mass resignation of actors from the Academy in October 1933, with the actors switching their allegiance to SAG. SAG joined with the SWG to publish "The Screen Guilds Magazine," a periodical whose editorial content attacked the Academy as a company union in the producers' pocket. SAG President Eddie Cantor, a friend of Roosevelt who had bee invited to spend the Thanksgiving Day holiday with the president, informed him of the guild's grievances over the NIRA code. Roosevelt struck down many of the movie industry code's anti-labor provisions by executive order.

The labor battles between the guilds and the studios would continue until the late 1930s, and by the time Frank Capra was elected president of the Academy in 1935, the post was an unenviable one. The Screen Directors Guild was formed at King Vidor's house on January 15, 1936, and one of its first acts was to send a letter to its members urging them to boycott the Academy Awards ceremony, which was three days away. None of the guilds had been recognized as bargaining agents by the studios, and it was argued to grace the Academy Awards would give the Academy, a company union, recognition. Academy membership had declined to 40 from a high of 600, and Capra believed that the guilds wanted to punish the studios financially by depriving them of the good publicity the Oscars generated.

But the studios couldn't care less. Seeing that the Academy was worthless to help them in its attempts to enforce wage cuts, it too abandoned the Academy, which it had financed. Capra and the Board members had to pay for the Oscar statuettes for the 1936 ceremony. In order to counter the boycott threat, Capra needed a good publicity gimmick himself, and the Academy came up with one, voting D.W. Griffith an honorary Oscar, the first bestowed since one had been given to Charles Chaplin at the first Academy Awards ceremony.

The Guilds believed the boycott had worked as only 20 SAG members and 13 SWG members had showed up at the Oscars, but Capra remembered the night as a victory as all the winners had shown up. However, 'Variety' wrote that "there was not the galaxy of stars and celebs in the director and writer groups which distinguished awards banquets in recent years." "Variety" reported that to boost attendance, tickets had been given to secretaries and the like. Bette Davis and Victor McLaglen had showed up to accept their Oscars, but McLaglen's director and screenwriter, John Ford and Dudley Nichols, both winners like McLaglen for The Informer (1935), were not there, and Nichols became the first person to refuse an Academy Award when he sent back his statuette to the Academy with a note saying he would not turn his back on his fellow writers in the SWG. Capra sent it back to him. Ford, the treasurer of the SDG, had not showed up to accept his Oscar, he explained, because he wasn't a member of the Academy. When Capra staged a ceremony where Ford accepted his award, the SDG voted him out of office.

To save the Academy and the Oscars, Capra convinced the board to get it out of the labor relations field. He also democratized the nomination process to eliminate studio politics, opened the cinematography and interior decoration awards to films made outside the U.S., and created two new acting awards for supporting performances to win over SAG.

By the 1937 awards ceremony, SAG signaled its pleasure that the Academy had mostly stayed out of labor relations by announcing it had no objection to its members attending the awards ceremony. The ceremony was a success, despite the fact that the Academy had to charge admission due to its poor finances. Frank Capra had saved the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and he even won his second Oscar that night, for directing Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936). At the end of the evening, Capra announced the creation of the Irving Thalberg Memorial Award to honor "the most consistent high level of production achievement by an individual producer." It was an award he himself was not destined to win.

By the 1938 awards, the Academy and all three guilds had buried the hatchet, and the guild presidents all attended the ceremony: SWG President Dudley Nichols, who finally had accepted his Oscar, SAG President Robert Montgomery, and SDG President King Vidor. Capra also had introduced the secret ballot, the results of which were unknown to everyone but the press, who were informed just before the dinner so they could make their deadlines. The first Irving Thalberg Award was given to long-time Academy supporter and anti-Guild stalwart Darryl F. Zanuck by Cecil B. DeMille, who in his preparatory remarks, declared that the Academy was "now free of all labor struggles."

But those struggles weren't over. In 1939, Capra had been voted president of the SDG and began negotiating with AMPP President 'Joseph Schenck', the head of 20th Century-Fox, for the industry to recognize the SDG as the sole collective bargaining agent for directors. When Schenck refused, Capra mobilized the directors and threatened a strike. He also threatened to resign from the Academy and mount a boycott of the awards ceremony, which was to be held a week later. Schenck gave in, and Capra won another victory when he was named Best Director for a third time at the Academy Awards, and his movie, You Can't Take It with You (1938), was voted Best Picture of 1938.

The 1940 awards ceremony was the last that Capra presided over, and he directed a documentary about them, which was sold to Warner Bros' for $30,000, the monies going to the Academy. He was nominated himself for Best Director and Best Picture for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), but lost to the Gone with the Wind (1939) juggernaut. Under Capra's guidance, the Academy had left the labor relations field behind in order to concentrated on the awards (publicity for the industry), research and education.

"I believe the guilds should more or less conduct the operations and functions of this institution," he said in his farewell speech. He would be nominated for Best Director and Best Picture once more with It's a Wonderful Life (1946) in 1947, but the Academy would never again honor him, not even with an honorary award after all his service. (Bob Hope, in contrast, received four honorary awards, including a lifetime membership in 1945, and the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian award in 1960 from the Academy.) The SDG (subsequently renamed the Directors Guild of America after its 1960 with the Radio and Television Directors Guild and which Capra served as its first president from 1960-61), the union he had struggled with in the mid-1930s but which he had first served as president from 1939 to 1941 and won it recognition, voted him a lifetime membership in 1941 and a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1959.

Whenever Capra convinced studio boss Harry Cohn to let him make movies with more controversial or ambitious themes, the movies typically lost money after under-performing at the box office. The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1932) and Lost Horizon (1937) were both expensive, philosophically minded pictures that sought to reposition Capra and Columbia into the prestige end of the movie market. After the former's relative failure at the box office and with critics, Capra turned to making a screwball comedy, a genre he excelled at, with It Happened One Night (1934). Bookended with You Can't Take It with You (1938), these two huge hits won Columbia Best Picture Oscars and Capra Best Director Academy Awards. These films, along with Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), and It's a Wonderful Life (1946) are the heart of Capra's cinematic canon. They are all classics and products of superb craftsmanship, but they gave rise to the canard of "Capra-corn." One cannot consider Capra without taking into account The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1932), American Madness (1932), and Meet John Doe (1941), all three dark films tackling major issues, Imperialism, the American plutocracy, and domestic fascism. Capra was no Pollyanna, and the man who was called a "dago" by Mack Sennett and who went on to become one of the most unique, highly honored and successful directors, whose depictions of America are considered Americana themselves, did not live his cinematic life looking through a rose-colored range-finder

In his autobiography "The Name Above the Title," Capra says that at the time of American Madness (1932), critics began commenting on his "gee-whiz" style of filmmaking. The critics attacked "gee whiz" cultural artifacts as their fabricators "wander about wide-eyed and breathless, seeing everything as larger than life." Capra's response was "Gee whiz!" Defining Hollywood as split between two camps, "Mr. Up-beat" and "Mr. Down-beat," Capra defended the up-beat gee whiz on the grounds that, "To some of us, all that meets the eye IS larger than life, including life itself. Who ca match the wonder of it?" Among the artists of the "Gee-Whiz:" school were Ernest Hemingway, Homer, and Paul Gauguin, a novelist who lived a heroic life larger than life itself, a poet who limned the lives of gods and heroes, and a painter who created a mythic Tahiti, the Tahiti that he wanted to find. Capra pointed to Moses and the apostles as examples of men who were larger than life. Capra was proud to be "Mr. Up-beat" rather than belong to "the 'ashcan' school" whose "films depict life as an alley of cats clawing lids off garbage cans, and man as less noble than a hyena. The 'ash-canners,' in turn, call us Pollyannas, mawkish sentimentalists, and corny happy-enders."

Capra was a populist, and the simplicity of his narrative structures, in which the great social problems facing America were boiled down to scenarios in which metaphorical boy scouts took on corrupt political bosses and evil-minded industrialists, created mythical America of simple archetypes that with its humor, created powerful films that appealed to the elemental emotions of the audience. The immigrant who had struggled and been humiliated but persevere due to his inner resolution harnessed the mytho-poetic power of the movie to create proletarian passion plays that appealed to the psyche of the New Deal movie-goer. The country during the Depression was down but not out, and the ultimate success of the individual in the Capra films was a bracing tonic for the movie audience of the 1930s. His own personal history, transformed on the screen, became their myths that got them through the Depression, and when that and the war was over, the great filmmaker found himself out of time. Capra, like Charles Dickens, moralized political and economic issues. Both were primarily masters of personal and moral expression, and not of the social and political. It was the emotional realism, not the social realism, of such films as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), which he was concerned with, and by focusing on the emotional and moral issues his protagonists faced, typically dramatized as a conflict between cynicism and the protagonist's faith and idealism, that made the movies so powerful, and made them register so powerfully with an audience.

- IMDb Mini Biography By: Jon C. Hopwood

Spouse (2)

Lou Capra (1 February 1932 - 1 July 1984) ( her death) ( 4 children)

Helen Howell (25 November 1923 - 16 August 1929) ( divorced)

Trade Mark (3)

His films normally center around a simple man who tries to fight corruption in a society.

Montage of newspaper headlines

Often cast James Stewart, Gary Cooper, and Cary Grant

Trivia (45)

Studied electrical engineering at CalTech, and only began working in films as a temporary summer job.

Awarded American Film Institute Life Achievement Award in 1982.

Was once a gag man for the Keystone Film Company (best known for its Keystone Kops shorts).

Father of Frank Capra Jr. (March 20, 1934-December 19, 2007), John Capra (April 24,1935-August 23, 1938), Lulu Capra (b. September 16, 1937), and Tom Capra (b. February 12, 1941). Family lived in Fallbrook, CA.

President of the Screen Directors Guild from 1939-41.

President of the Directors Guild of America (DGA) from 1960-61.

He got his first film assignment by answering an ad in a Los Angeles newspaper.

Critics dubbed his movies as "Capra-corn" for their simple and sappy storylines.

Was voted the 9th Greatest Director of all time by "Entertainment Weekly".

Biography in: John Wakeman, editor. "World Film Directors, Volume One, 1890-1945." Pages 96-103. New York: The H.W. Wilson Company, 1987.

When he was nominated for his first Best Director Oscar in 1933 (for Lady for a Day (1933)), presenter Will Rogers merely opened the envelope and said "Come and get it, Frank!" Already halfway to the stage, Capra realized that Rogers wasn't referring to him, but to Frank Lloyd, who was getting the Oscar for Cavalcade (1933).

Directed ten different actors in Oscar-nominated performances: May Robson, Clark Gable, Claudette Colbert, Gary Cooper, H.B. Warner, Spring Byington, James Stewart, Claude Rains, Harry Carey and Peter Falk. Gable and Colbert won Academy Awards for their roles in It Happened One Night (1934).

His father, Turiddu, died in a horrible factory accident in 1915. When the aging man was working some gears, he got caught in the gears and was nearly ripped in half.

Hosted the Academy Awards in 1936 and 1939.

Emigrated to America with his parents in 1903. They settled in Los Angeles, where his older brother was already living.

President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences from 1935-39.

Head of jury at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1958.

Had a son, Johnny, who died in 1938, at age 3, from complications arising from a tonsillectomy.

Claimed that both Barbara Stanwyck and Frank Sinatra "left their best scenes in rehearsal," saying that all subsequent takes got stale quickly. Capra would often shoot scenes with them without any rehearsing at all. This used to drive the other actors nuts. Edward G. Robinson once stormed off the set of A Hole in the Head (1959) and asked to be let out of his contract because he was used to rehearsing all his roles.

Said Jean Arthur would get real tense and often become violently sick before shooting began. However, he said she always managed to compose herself when the cameras started to roll and acted as though nothing was wrong.

Claimed that Frank Sinatra had the potential to be the best actor there ever was. He once told Frank to quit his musical career and concentrate solely on acting and that if he did he would go down as the greatest actor who ever lived.

Inspired the adjective "Capraesque".

He was awarded the American National Medal of the Arts in 1986 by the National Endowment of the Arts in Washington, DC.

Is the second most-represented filmmaker (behind Steven Spielberg) on the American Film Institute's 100 Most Inspiring Movies of All Time, with four of his films on the list. They are: Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936) at #83, Meet John Doe (1941) at #49, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) at #5, and the most uplifting movie of all time, It's a Wonderful Life (1946).

Heavily influenced friend Thomas R. Bond II, a producer/director who gained most of his knowledge in directing and producing from Capra.

Was originally supposed to write and direct Circus World (1964) but quit the project when star John Wayne rejected Capra's script and instead insisted it be written by his old friend, James Edward Grant.

Although most of his films were written by individuals on the political left who tended to exude the spirit of the New Deal, Capra himself was a lifelong conservative Republican who never voted for President Franklin D. Roosevelt, admired Francisco Franco and Benito Mussolini and later, during the McCarthy "Red Scare" era served as a secret FBI informer for his friend J. Edgar Hoover.

Interviewed in "Talking to the Piano Player: Silent Film Stars, Writers and Directors Remember" by Stuart Oderman (BearManor Media).

Profiled in "Conversations with Directors: An Anthology of Interviews from Literature/Film Quarterly", E.M. Walker, D.T. Johnson, eds. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2008.

Biography in: "The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives". Volume 3, 1991-1993, pages 96-98. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2001.

A staunch opponent of abortion and donated funds to support the Human Life Amendment.

Honored on a US postage stamp in May 2012 (with John Ford, Billy Wilder and John Huston).

Upon his death his remains were interred at Coachella Valley Public Cemetery in Coachella, CA. His location plot is Lot 289, Unit 8, Block 77.

Among many unrealized projects in his long career, one to which he was especially devoted was a film about the life of Saint Paul , to star Frank Sinatra.

His last name means "goat" in his native Italian.

MGM production chief Irving Thalberg wanted to borrow Capra from Columbia Pictures and offered Columbia chief Harry Cohn $50,000, the use of an MGM star of his choice for a film and Capra's choice of properties. The director selected "Soviet," the story of an American engineer building a dam in Russia. It was to star Clark Gable, Joan Crawford, Marie Dressler and Wallace Beery. Thalberg's illness caused MGM boss Louis B. Mayer to cancel the production but MGM made good on the payment and the loan-out.

Capra's classmates at Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles included singer Lawrence Tibbett and future war hero Jimmy Dolittle.

About Ladies of Leisure (1930) with a very young Barbara Stanwyck, Capra later wrote that he would have married her if both of them had been free at the time.

Colleen Moore recalled that Capra directed the cameo appearance by Harry Langdon in the First National picture Ella Cinders (1926).

Columbia Pictures boss Harry Cohn was notorious for coming on the set and trying to override directors' decisions--usually for monetary reasons--so when Capra won his first Oscar, he re-negotiated his contract with Columbia and insisted on a proviso that forbade Cohn from appearing on the set of any film Capra was making for Columbia. He got it.

His films were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture in four consecutive years: Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Lost Horizon (1937), You Can't Take It with You (1938) and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). Of the four films in question, You Can't Take It with You (1938) was the only one to win the award. The only director to receive more consecutive Best Picture nominations is William Wyler at seven.

His play, "It's A Wonderful Life: Live in Chicago!" at the American Blues Theater in Chicago, Illinois was nominated for a 2017 Joseph Jefferson Equity Award for Midsize Play Production.

The cast of his play, "It's a Wonderful Life: Live in Chicago" at the American Blues Theater in Chicago, Illinois was nominated for a 2017 Joseph Jeffersoon Equity Award for Ensemble.

Directed seven Academy Award Best Picture nominees: Lady for a Day (1933), It Happened One Night (1934), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Lost Horizon (1937), You Can't Take It with You (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and It's a Wonderful Life (1946). It Happened One Night and You Can't Take It with You both won Best Picture.

He has directed six films that have been selected for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically or aesthetically" significant: The Strong Man (1926), The Power of the Press (1928), It Happened One Night (1934), Lost Horizon (1937), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and It's a Wonderful Life (1946). His government WW2 documentary series "Why We Fight" is also in the registry: Prelude to War (1942), The Nazis Strike (1943), Divide and Conquer (1943), The Battle of Britain (1943), The Battle of Russia (1943), The Battle of China (1944) and War Comes to America (1945).

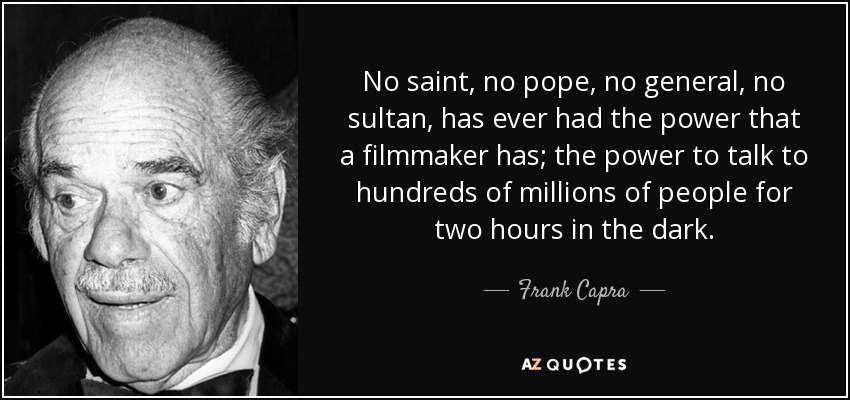

Personal Quotes (29)

Behind every successful man there stands an astonished woman.

Compassion is a two-way street.

My advice to young filmmakers is this: Don't follow trends. Start them!

I thought drama was when the actors cried. But drama is when the audience cries.

There are no rules in filmmaking. Only sins. And the cardinal sin is dullness.

[on Marilyn Monroe] Breasts she had. And a wiggly figure. But to me sex is class, something more than a wiggly behind. If it weren't, I know 200 w***** who would be stars.

[James Stewart's] appeal lay in being so unusually usual.

[upon receiving his AFI Lifetime Achievment Award] I'd be the first to admit I'm a damn good director.

Film is a disease. When it infects your bloodstream, it takes over as the number one hormone; it bosses the enzymes; directs the pineal gland; plays Iago to your psyche. As with heroin, the antidote to film is more film.

[on his early dream to be an astronomer] I could study the stars and the planets forever. I always wanted to know why, why . . . Pictures changed my mind. I was too far along in the movie business. But when I go back to Caltech now and hear about things I'm not familiar with, like black holes, goddamn! I get mad. How the hell I ever refused that I don't know. But it seems like motion pictures have a terrible hold on me. I don't know what it is.

A hunch is creativity trying to tell you something.

Do not help the quick moneymakers who have delusions about taking possession of classics by smearing them with paint.

In our film profession you may have [Clark Gable's] looks, [Spencer Tracy's] art, [Marlene Dietrich's] legs or [Elizabeth Taylor's] violet eyes, but they don't mean a thing without that swinging thing called courage.

[on Preston Sturges] Jesus, he was a strange guy. Carried his own hill with him, I tell you.

[on Jean Arthur] Never have I seen a performer with such a chronic case of stage jitters. They weren't butterflies in her stomach. They were wasps.

There is one word that aptly describes Hollywood--"nervous".

[on directing Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night (1934)] Colbert fretted, pouted and argued about her part. Challenged my slaphappy way of shooting scenes. Fussed constantly. She was a tartar, but a cute one.

[on It's a Wonderful Life (1946)] It's the damnedest thing I've ever seen! The film has a life of its own now, and I can look at it like I had nothing to do with it. I'm like a parent whose kid grows up to be President. I'm proud . . . but it's the kid who did the work. I didn't even think of it as a Christmas story when I first ran across it. I just liked the idea.

[on Philip Van Doren Stern] The man whose Christmas tale was the spark that set me off into making my favorite film, It's a Wonderful Life (1946).

[on It's a Wonderful Life (1946)] I thought it was the greatest film I ever made. Better yet, I thought it was the greatest film anybody had ever made. It wasn't made for the oh-so-bored critics or the oh-so-jaded literati. It was my kind of film for my kind of people.

It's a Wonderful Life (1946) sums up my philosophy of filmmaking. First, to exalt the worth of the individual. Second, to champion man--plead his causes, protest any degradation of his dignity, spirit or divinity. And third, to dramatize the viability of the individual--as in the theme of the film itself . . . there is a radiance and glory in the darkness, could we but see, and to see we only have to look. I beseech you to look.

[when asked if there was still a way to make movies with the values and ideals in his films] Well if there isn't, we might as well give up.

[the theme of It's a Wonderful Life (1946)] The individual's belief in himself. I made it to combat a modern trend toward atheism.

[to James Stewart when he hadn't yet figured out the story for It's a Wonderful Life (1946)] I haven't got a story. This is the lousiest piece of cheese I ever heard of. Forget it, Jimmy . . . Forget it!

[after Philip Van Doren Stern sent him a Christmas card that formed the basis for It's a Wonderful Life (1946)] I thank you for sending it and I love you for creating it.

[returning to directing after World War II] I was scared to death.

[on "The Greatest Gift", the short story that inspired It's a Wonderful Life (1946)] My goodness, this thing hit me like a ton of bricks. It was the story I had been looking for all my life. The kind of an idea that when I get old and sick and scared and ready to die--they'd say, "He made 'The Greatest Gift'."

[on the coming of sound] Everybody in Hollywood was scared to death of sound, but I knew all about sound waves from freshman physics.

It Happened One Night (1934) is the real [Clark Gable]. He was never able to play that kind of character except in that one film. They had him playing these big, huff-and-puff he-man lovers, but he was not that kind of guy. He was a down-to-earth guy, he loved everything, he got down with the common people. He didn't want to play those big lover parts; he just wanted to play Clark Gable, the way he was in "It Happened One Night", and it's too bad they didn't let him keep up with that.

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson