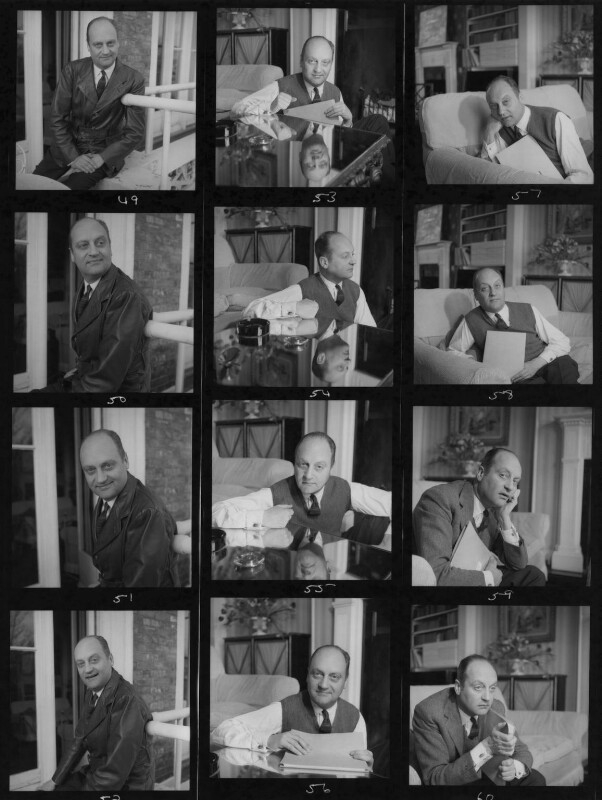

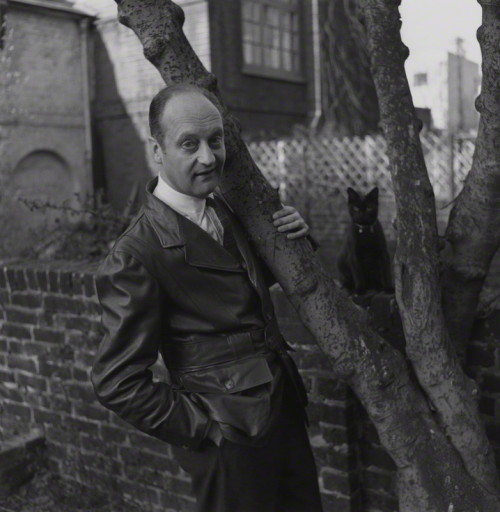

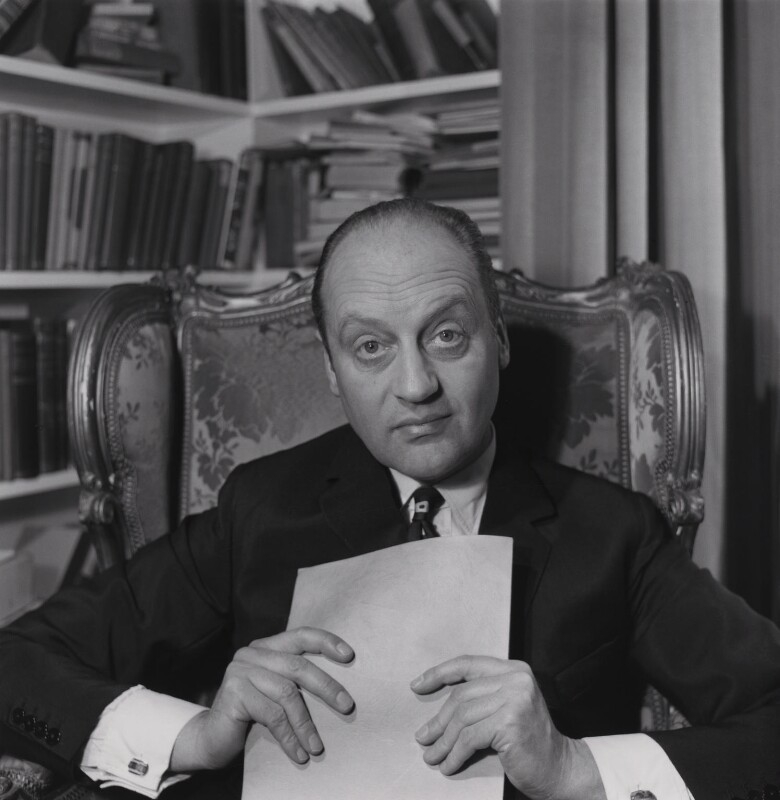

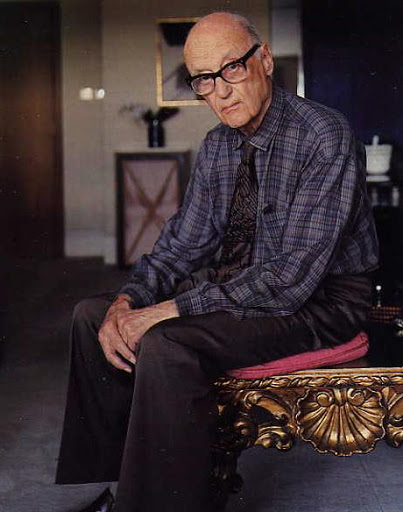

Frith Banbury

Eclectic stalwart of London's West End as director, producer and actor

Michael Billington

15 May 2008 19.32 EDT

Frith Banbury, who has died aged 96, was a director, producer and actor who seemed to epitomise the glamour and style of the West End theatre in its 1940s and 50s heyday. Yet, although he worked with just about every leading actor and actress and staged many plays by Rodney Ackland, NC Hunter, Wynyard Browne, Terence Rattigan and Robert Bolt, he was never a fully paid-up member of the theatrical establishment: he was much more eclectic in his tastes and adventurous in his outlook - apart from being more durable - than almost all of his contemporaries in the commercial theatre.

Born in Plymouth, the son of a rear-admiral and his wealthy Russian-Jewish wife, the young Banbury rebelled from the start against authority. He rejected his father's naval background. At Stowe school, Buckinghamshire, he refused to join the Officer Training Corps, later becoming a conscientious objector. And, although going up to Oxford to read modern languages in 1930, he spent most of his time acting and partying and left after a year without taking a degree.

Theatre had become his passion from the age of six, when he was taken to the London Hippodrome to see his first play. So, after leaving Oxford, he enrolled at Rada, where his fellow students included Joan Littlewood and Rachel Kempson. From there he went more or less straight into mainstream theatre understudying - and eventually playing the lead in - Gordon Daviot's Richard of Bordeaux, and walking on in Gielgud's 1934 New Theatre Hamlet. ("Banbury, don't be so prissy," said Gielgud, stripping him of the few lines he had).

He also did three summer seasons in rep in Perranporth in Cornwall, which led to a lifelong friendship with its rumbustious directors, Robert Morley and Peter Bull.

With the outbreak of war, Banbury - already a card-carrying member of the Rev Dick Sheppard's Peace Pledge Union - registered as a conscientious objector. Asked if he was prepared to do farm work, he replied: "Prepared, but not capable." So he found himself continuing to work as an actor: he appeared in a wide variety of intimate revues, played a season in rep at Cambridge, took the lead in The Government Inspector at the Glasgow Citizens Theatre and did an Ensa tour of the newly liberated Europe in 1945 with While the Sun Shines by his Oxford contemporary, Terence Rattigan.

But, although he was an accomplished comic actor, it was after the war that Banbury found his true metier as a director of plays. He was invited back to Rada, where he directed Pinero's farce, The Times. According to Charles Duff's The Lost Summer, which uses Banbury's career as an epitome of postwar commercial theatre, this was the moment of revelation. Confronted by a cast of 22 students, Banbury suddenly found himself spontaneously and naturally directing them.

He made his professional break-through by taking a six-month option on a work called Dark Summer written by a friend and fellow pacifist, Wynyard Browne. He took it to Binkie Beaumont at HM Tennent Ltd, the management that monopolised West End theatre and had a subsidiary non-profit company that did much of its work at the Lyric Hammersmith. It was there that Browne's play opened in 1947 and was enough of a success to come into the West End. It also established Banbury as a skilled director of traditional English middle-class plays and led, in the next few years, to work on such huge successes as Browne's The Holly and the Ivy, Hunter's Waters of the Moon and Rattigan's The Deep Blue Sea.

Banbury was excellent at getting fine performances out of actors. But, looking back over his years in commercial theatre, he was both perceptive and funny. He once told me that Peggy Ashcroft's success as the outwardly conventional but sexually passionate Hester Collyer in The Deep Blue Sea was due to the fact that it touched something deep in her: an observation which I quoted in my biography and which led to my one serious argument with my subject.

In 1996, a group of British theatre folk were also invited to a conference at the University of Texas at Austin, to which Banbury had donated his papers. He stole the show with his memories of the Beaumont years and, in particular, with his stories about NC Hunter. Apparently, after Hunter's death, his widow - an ardent spiritualist and shrewd executor - was approached by Duncan Weldon about the prospect of reviving Waters of the Moon, but on a reduced royalty. To Weldon's astonishment, Mrs Hunter's initial reaction was: "I'll have to ask Norman." Having made suitable contact with her husband on the other side, Mrs Hunter came back to Weldon a week or so later and decisively announced: "Norman says no."

That story showed Banbury's innate impishness. But he was also a passionate advocate of work he believed in. In the 1950s, he waged a fierce campaign on behalf of Rodney Ackland, long before he was fashionable, directing The Pink Room (later retitled Absolute Hell), which was critically reviled, and A Dead Secret which, with Paul Scofield in the lead, enjoyed a respectable run. Banbury also gave Robert Bolt a kick-start directing (and co-presenting) Flowering Cherry as well as The Tiger and the Horse. He also, surprisingly, directed in 1958 the first play by a black author to be seen at the Royal Court: Errol John's Moon on a Rainbow Shawl, which won an Observer new play competition.

With the slow decline of commercial theatre, Banbury's influence gradually waned, though he directed notable revivals of Dear Octopus in the 1960s and On Approval in the 70s. He also carried on working to the end of his life: only illness forced him to withdraw, in his mid-80s, from a Chichester revival of Ackland's After October. He was awarded the MBE in 2000 for his services to theatre.

From my acquaintanceship with him, he was a man of fascinating contradictions: a rebel against authority who yet believed strongly in theatrical discipline; an instinctive European who made his name directing quintessentially English middle-class plays; an embodiment of West End values who had a ravenous appetite for new writing. He will be remembered best as a first-rate naturalistic director who gave the commercial theatre a dignity and style that now seems a distant memory.

He is survived by a niece and nephew.

· Frith (Frederick Harold) Banbury, theatrical director, producer and actor, born May 4 1912; died May 14 2008

America is at a crossroads ...

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson