Groucho Marx, Comedian, Dead; Movie Star and TV Host Was 86

By Albin Krebs Aug. 20, 1977 Special to The New York Times

LOS ANGELES, Aug. 19—Groucho Marx, the comedian, died tonight at the Cedar Sinai Medical Center here after failing to recover from a respiratory ailment that hospitalized him on June 22. He was 86 years old.

Marx, whose entertainment career began almost 70 years ago and ranged from vaudeville to television, slumped into semiconsciousness late last night and failed quickly, the doctors said.

His death was attributed to pneumonia. Marx, with his brothers Chico, Harpo, Gummo, and Zeppo, conquered Broadway in such shows as “The Cocoanuts” and “Animal Crackers,” and ‐then moved to Hollywood where they started an almost legendary series of movies, highlighted by such pictures as “A Night at the Opera” and “A Day at the Races. ”

At Groucho's death, Zeppo became the only survivor of the five brothers.

Groucho first entered the hospital in March, suffering from a hip ailment. Following surgery to repair a damaged hip joint, he was released in late March.

Subsequently, he reinjured his hip and returned for more surgery.

He stayed 11 days, was released, and was readmitted after only one day, suffering from a respiratory condition. He did not leave the hospital again.

During his hospitalization, he was not made aware of a bitter court battle over the stewardship of his estate.

With him when he died were his son, Arthur; Arthur's wife, Lois, and Groucho's grandson, Andrew.

A hospital spokesman said no funeral arrangements had been made as of tonight.

Master of the Insult

Effrontery, of the most lunatic, unquenchable sort, was the chief stock in trade of Groucho Marx. As the key man in the most celebrated brother act in motion pictures, he developed the insult into an art form. And he used the insult, delivered with maniacal glee, to shatter the egos of the pompous—and to plunge his audiences into helpless laughter.

The comedy world of Groucho Marx and his brothers Harpo and Chico was wildly chaotic, grounded in slapstick farce, lowbrow vaudeville corn, free-spirited anarchy, and zany assaults on the myths and virtues of middle‐class America.

The private world of Groucho Marx was not far removed from his public image.

He was the kind of man who could, during his wedding ceremony, fling insults at the minister and, 21 years later, when his wife was leaving him for good, shake hands with her and say, “Well it's been nice knowing you; if you're ever in the neighborhood again, drop in. ”

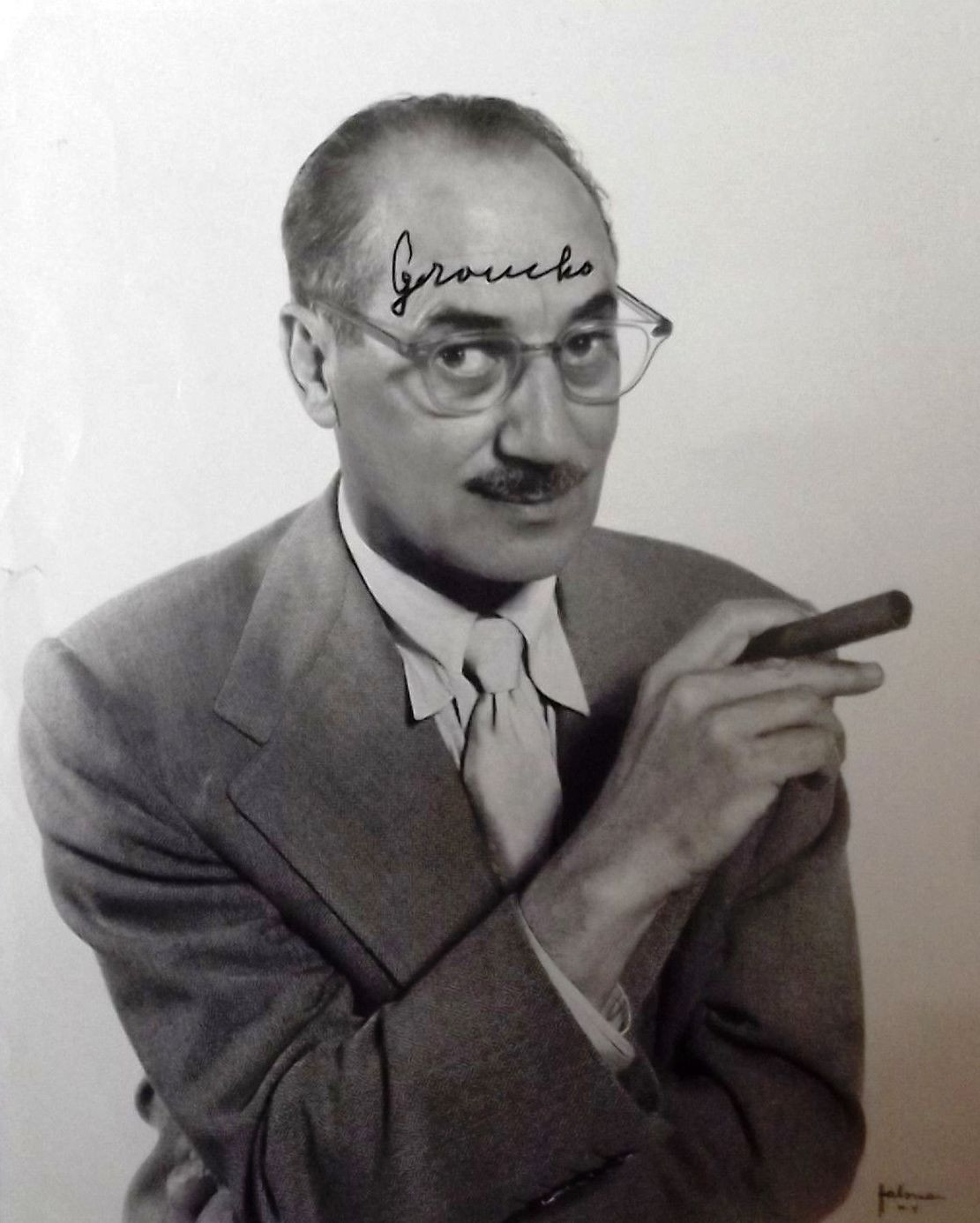

Groucho was larger and more antic than life. He was the gruesomely stooped man in the swallowtail coat who took great loping steps across the stage or screen, holding a long, plump cigar behind him. His seemingly depraved eyes rolled and leered from behind steel-rimmed glasses. Below his large nose smudge of black greasepaint passed for a mustache.

His humor was based on the improbable, the unexpected, the outrageous.

In a Marx Brothers play he would interrupt a scene by stopping at the footlights to inquire urgently, “Is there a doctor in the house?” When an unsuspecting physician rose, he would demand to know: “If you're a doctor, why aren't you at the hospital making your patients miserable, instead of wasting your time here with that blonde?”

During one of his television quiz shows, which was immensely popular in the 1950s, when a contestant was asked her age and said she was “approaching 40,” he replied, “From which direction?”

Aimed at Deflation

But Groucho's expertly delivered, rapid-fire insults were more mad than maddening; they really weren't unkind, for they evolved from his interest in humor that deflated rather than annihilated. This quality was, in fact, the distinguishing mark of the comedy so richly dispensed by Groucho Marx, his brothers, and their great contemporaries, such as Charles Chaplin, W. C. Fields, and Buster Keaton.

“It was the type of humor that made people laugh at themselves,” Groucho said in 1968, “rather than the sort that prevails today—the sick, black, merely smart‐aleck stuff designed to evoke malicious laughter at the other fellow. ”

Throughout his hectic life, the comedian remained able to laugh at himself.

He even appeared not to take seriously the fact that his early years were passed in extreme poverty. For example, when it was suggested that his rags‐to‐riches rise bore Lincolnesque overtones, he said, 'There weren't any rails to split in the neighborhood around 93d Street and Third Avenue. Just the third rail on the El, and there wasn't much of a future in fooling around with that. ”

Julius Henry Marx was born Oct. 2, 1890, in a tenement on East 93d Street.

His Alsatian‐born father, Samuel Marx, was an unsuccessful tailor; his mother, the former Minnie Schoenberg, was the stage‐struck sister of Al Shean, of the comedy team of Gallagher and Shean.

Mrs. Marx pushed all five of her sons into show business, partly because she was the embodiment of the “stage mother,” but also because every member of the family had to be a breadwinner. At 10, Groucho was singing soprano with the Gus Edwards vaudeville troupe, and at 14 he completed his formal education by quitting P. S. 86.

“If I intended to eat, I would have to scratch for it,” he wrote years later.

Mother Assembled Act

Still in his teens, Groucho got a $ 4-a-week job with the Le May Trio, an act that broke up in Denver, leaving him penniless.

He worked in a grocery store long enough to earn train fare back to New York, where his mother was putting together an act called the Six Musical Mascots.

It consisted of Groucho and two of his brothers, Adolph (later Harpo) and Milton (Gummo), an attractive soprano named Janie O'Riley, Mts. Marx and her sister Hannah. Mrs. Marx soon realized that she and her sister were so bad that the act was doomed unless they left it. They retired from show business.

What was left was the Four Nightingales, an act that, in the course of its travels through whistle‐stop towns, in the South and Midwest, changed its name to the Marx Brothers and Co. Harmony singing, popular on the vaudeville circuit at the time, was the basis of the act before the brothers fairly stumbled onto the format that was to make them famous.

They did so when they played a seedy little theater in Nacogdoches, Tex., in 1914.

“Our act was so lousy,” Groucho said, “that when word passed through the audience of numbskull Texans that a mule had run away, they got up en masse to go out and see something livelier. We were accustomed to heckling and insults, but that made us furious, so when those guys wearing ten‐gallon hats over pintsized brains came back, we let them have it. It wasn't the best line I ever ad‐libbed, but I recall I told them ‘Nacogdoches—is full of roaches. ’ And—ultimate insult I called those Texans ‘damn Yankees. '”

The audience loved the insults and the ad‐libs, and from that point on, the Marxes sang less and worked in more jokes, puns, and one‐liners. They used carefully plotted sketches but never hesitated to throw in topical ad‐libs.

Hobby of Nicknames

The Marx Brothers perfected their style and characterizations over several years of one‐night stands, They got their nutty names from Art Fisher, a monologuist whose hobby was making up nicknames. Harpo's name came from the instrument he played, Gummo's from his gumshoes, Chico's from his reputation as a lady‐killer, and Zeppo's from Zippo, star of the chimpanzee act. Because of his saturnine disposition, Groucho's name was a natural.

Groucho first wore his famous frock coat in a sketch called “Fun in Hi Skule,” in which he played the professor. He adopted the omnipresent cigar because he liked to smoke cigars in the first place, and they served as useful props. If you forget a line,” he said, “all you have to do is stick the cigar in your mouth and puff on it until you think of what you've forgotten. ”

The painted‐on mustache, which was Groucho's chief trademark for 30 years, until he grew a real one, resulted from a dispute with the manager of the Fifth Avenue Theater. One night he arrived too late to put on his paste‐on mustache. Instead he drew one on with greasepaint. After the show the manager demanded “the same mustache you gave ‘em at the Palace,” so Groucho handed him the fake mustache. The greasepaint smear was thenceforward substituted.

The Marxes’ first Broadway hit was “I'll Say She Is,” in 1924. It was a success largely on the strength of a rhapsodic review in The New Yorker by Alexander Woollcott who spent the rest of his life pouring praise upon the brothers, Groucho in particular.

In 1929 Groucho very nearly suffered a nervous breakdown. He and his brothers filmed “The Cocoanuts,” which had been their second Broadway hit, on Long Island during the day, and appeared nightly in the stage version of “Animal Crackers” (which was committed to film in 1930). He had invested all his savings, $240,000, in the stock market, and lost it all in the crash.

A Favorite of Fans

“Animal Crackers” gave Groucho his most celebrated character, Capt. Jeffrey T. Spaulding, the bumbling African explorer, as well as a monologue that Groucho aficionados have loved over the years. The monologue relied on Groucho's wildly comic delivery, but even in print, it suggested the outrageousness of the Marx's manner.

The monologue is a lampoon of the African adventure saga, delivered by Groucho (Spaulding) before guests at a rich woman's soiree. “Africa is God's country, and He can have it,” Groucho begins. “Well, sir, we left New York drunk and early on the morning of Feb. 2. After 15 days on the water and six on the boat, we finally arrived on the shores of Africa… One morning I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas, I don't know…. But that's entirely irrelevant.. ” And so on.

In “Animal Crackers,’ as well as eight other Marx Brothers pictures, Groucho's long‐suffering comic foil was Margaret Dumont. whose haughty demeanor suggested the epitome of the grande dame. In their scenes, Groucho was invariably the mangy lover intent on fleecing the rich society matron of her last cent, while at the same time hurling at her the most ungentlemanly insults.

“You're the most beautiful woman I've ever seen, which doesn't say much for you,”

he ardently told Miss Dumont in “Animal Crackers. ” In “Duck Soup” (1 933). as he, Chico, and Harp° fended off Miss Dumont's enemies, he said of her, “Remember, we're fighting for her honor—which is probably more than she ever did. ”

Surprise for Thalberg

The most popular of the Marx movies was “A Night at the Opera” (1935), produced for Metro‐Goldwyn‐Mayer by Irving Thalberg, who Quickly learned he was dealing with zanies. After he kept the Marxes waiting in his office for more than two hours, Grouch() instructed his brothers to disrobe. When Mr. Thalberg finally came out to greet them, he found Groucho, Chico, and Harpo before the fireplace, roasting marshmallows in the nude.

Groucho was the quack Dr. Hackenbush in “A Day at the Races” (1937). It was his favorite role because, he said, “It tickled up the medical profession, and I think it can stand a bit of lampooning now and then. ”

By. 1939, with the release of “The Marx Brothers at the Circus,” he and his brothers were tired of making movies. “I continued to appear in them,” he said, “but the fun had gone out of picture‐making. I was like an old pug, still going through the motions, but now doing it solely for the money. ”

Career on His Own

The Marx Brothers wound up their M‐GM contract with “Go West” (1940) and “The Big Store” (1941), They were idle until 1946, when they made “A Night’ in Casablanca,” and broke up the Brother Act for good in 1949 with “Love Happy. ”

(Gummo had left the act many years previously, even before the brothers made their Broadway debut, to become a theatrical agent. Zeppo quit the act after “Duck Soup” in 1933, also to become an agent. C hico died in 1961, Harpo three years later. )

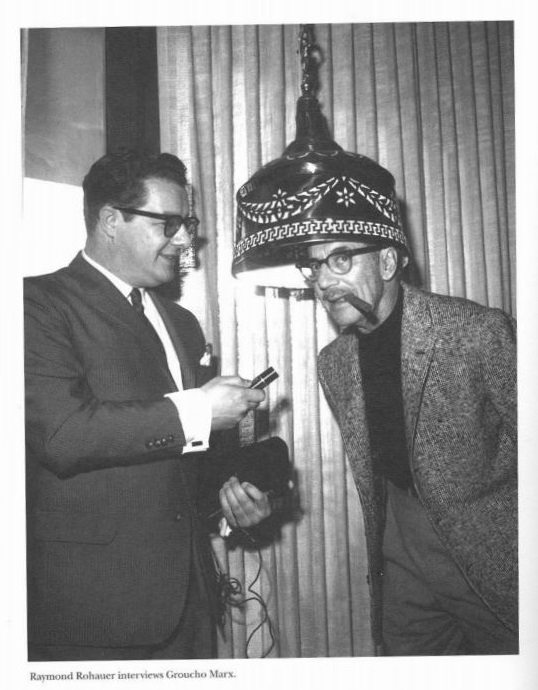

With “You Bet Your Life,” a radio‐television quiz show that began in 1947 and lasted a decade, Groucho forged a new career for himself as a single. The program, at one time the highest‐rated TV show in the country and the winner of several broadcasting awards, featured the quizmaster's irreverent insult humor rather than jackpot cash awards.

On one program, when a contestant developed mike‐fright and was unable to utter a word, Groucho said, “Either this man is dead, or my watch is stopped. ”

Interviewing a tree surgeon, he asked, “Have you ever fallen out of any of your patients?”

Groucho's eccentric antics carried over into his private life.

He kept an air rifle beside his bed, and when he heard a howling dog, he would bound to the window to shoot at it. He drove his family to distraction, according to his son Arthur, by practicing on the guitar for stretches of six hours or playing Gilbert and Sullivan recordings into the wee hours.

He tried to master golf, with results so unsatisfactory that on one occasion, while playing on a course overlooking the Pacific, he walked to a cliff, dropped his golf balls one by, one into the sea, and then tossed his bagful of clubs after them.

“He turned away with a benignly happy look on his face,” a fellow player reported.

The comedian married his first wife, the former Ruth Johnson, in 1920, not long after he and his brothers opened in an act called “Home Again” at the Palace Theater—and landed at last in the big time. The wedding ceremony was as chaotic as a Marx Brothers' routine. While Chico and Harpo skittered about the room carrying potted palms, Groucho harangued the minister with remarks such as, “Why are you going so fast? This is a five‐buck ceremony. Aren't we entitled to at least five minutes of your time?” The marriage, which produced two children, Miriam and Arthur, lasted until 1942.

In 1945 he married the former Catherine Gorcey and they had a daughter, Melinda, of whom he was inordinately proud. When Melinda was prevented from swimming with friends in the pool at the country club that excluded Jews, her father wrote the club president an indignant, highly publicized letter in which he said, “Since my little daughter is only half‐Jewish, would it be all right if she went in the pool only up to her waist?”

His second marriage ended in divorce in 1950. He married a former model, Eden Hartford, in 1953, when he was past 60 and she was 24.

Battle Over Estate

That marriage broke up in 1969, and Groucho did not marry again. Still, for a number of years, he sought to maintain his image as a leering satyr and seldom let himself be seen in public without the company of a young and beautiful woman.

In 1972, when he returned to the New York stage for the first time in 43 years to give a one‐man, one‐performance show at Carnegie Hall, he was accompanied by Erin Fleming. Miss Fleming had been, his “secretary‐companion,” as she was described then, since his third divorce.

By the time of the Carnegie concert, Groucho, who had shaved four years off his actual age for decades, was no longer lying about the fact that he was past 80.

He looked it too. His voice was feeble and he could hardly hear, even with his hearing aid, but his eyes were still merrily bright.

Last November, he was to have been lionized in Washington, where he intended to present Marxian memorabilia, including the pith helmet he wore as Captain Spaulding in “Animal Crackers,” to the Smithsonian Institution. But the trip was canceled at the last minute, ostensibly because Miss Fleming had the flu and he would not go anywhere without her.

Groucho went to the hospital for an operation on his hip last March. As he was recuperating, confined to his Beverly Hills home, an unpleasant court battle went on over the management of his estate, which was estimated at $2. 5 million at the time he divorced his third wife.

Three years ago, Miss Fleming was appointed his guardian. She also was a temporary conservator for the estate and Groucho's son, Arthur Marx, sought to replace her in that position. According to the testimony, Miss Fleming, now 37, had exerted a baneful influence over Groucho, even threatening his well‐being, though others declared that she was the only reason he was clinging to life then.

The court compromised by appointing Groucho's friend of 45 years, Nat Perrin, the screenwriter, as temporary conservator pending a final decision.

Groucho's grandson, Andrew, 27, was later named permanent conservator.

Early in 1973, Groucho's son, Arthur, published “Son of Groucho,” a memoir. In it, he recalled his father as a singularly penurious man who, when going out to dine in an expensive Hollywood restaurant, would park blocks away to save a parking fee.

His stinginess notwithstanding, and despite the pains he took to make himself financially secure, Groucho, his son reported, was not terribly well off in his old age, chiefly because of the expensive alimony and property settlements resulting from his three divorces.

Shunner of Parties

Groucho's irresponsibility in his personal dealings was legendary. It was not unusual for him to call a friend in the middle of the night—this was one of his ways of taking the boredom out of his insomnia—and launch into a barrage of abuse:

“This is Professor Waldemar Strumbelknauff. Aren't you ashamed of yourself, for beating your children that way? If you were a man you'd come over here and knock my teeth out. If you were half a man you'd knock half my teeth out . . .

This is Groucho. How are you? As if I really care. ” And then he'd hang up.

He grew to hate New York because he was expected to wear a tie when he went out. He was so addicted to informal wear that he shunned parties, developing, immediately upon being told he was expected to go to one, “a grippy feeling.”

When he himself entertained, he often took leave of his guests at an early hour, telling them to “go ahead and get drunk on my booze and make fools of yourselves—

I don't care because I'm going to bed. ”

The comedian, who supplemented his meager formal education by reading omnivorously, greatly admired writers. He considered George Bernard Shaw's observation that “Groucho Marx is the world's greatest living actor” as the compliment of his lifetime. For some years he carried on a correspondence with T. S. Eliot, and in 1965 was invited to speak at a memorial service for the poet. Typically, he used the occasion to say something outrageous: “Apparently Mr. Eliot was a great admirer of mine—and I don't blame him. ”

He was a compulsive letter writer. In 1964 he wrote Gov. William Scranton of Pennsylvania to tell him he had heard him, during a broadcast, mispronounce a Yiddish term. “If you are going to campaign in Jewish neighborhoods,” he counseled the Governor, “rhyme mish‐mash with slosh. ”

A collection of his correspondence was published as “The Groucho Letters. ”

The Library of Congress asked him for his letters and papers, which included the manuscripts of two books he wrote, “Groucho and Me” and “Memoirs of Mangy Lover. ”

Groucho Marx was actually a moody man, those who knew him best said.

They insisted that beneath his brash, fast‐talking exterior, he was thoughtful, shy, and kindhearted. His longtime friend, the songwriter Harry Ruby, said, “The guy doesn't mean to be insulting; it's an involuntary notion with him, like a compulsion neurosis." And to his son, Arthur, Groucho was “a sentimentalist, but he'd rather be found dead than have you know it. ”

Groucho himself admitted that “my trouble is that I don't like to let just everybody get in a word edgewise, and can't stand anyone else having the last word. ”

To make sure this wouldn't happen to him ultimately, he took the precaution of writing his epitaph in advance: “I hope they buried me near a straight man. ”

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson