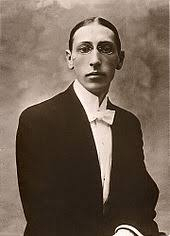

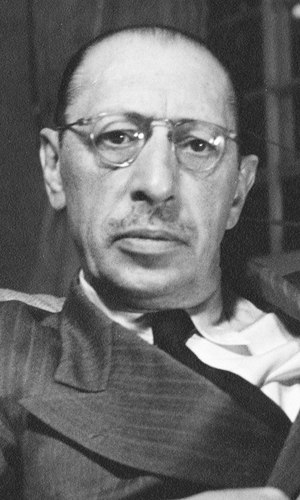

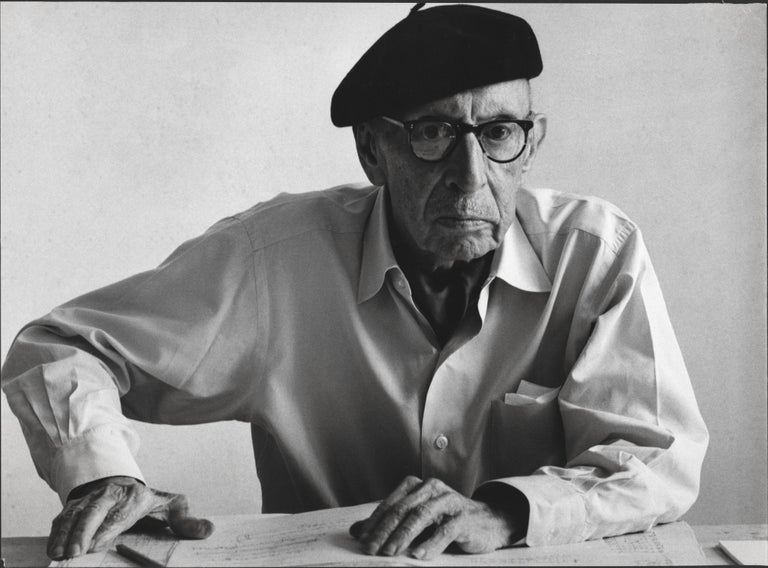

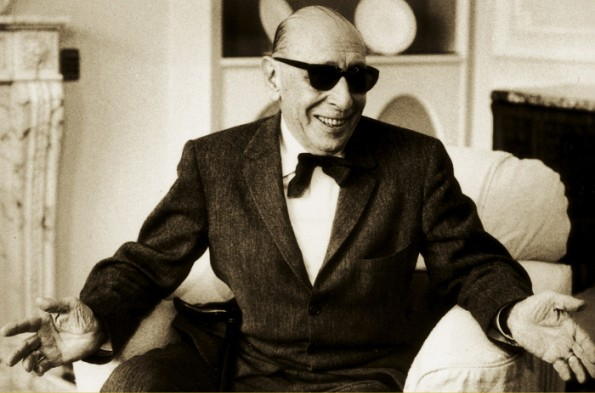

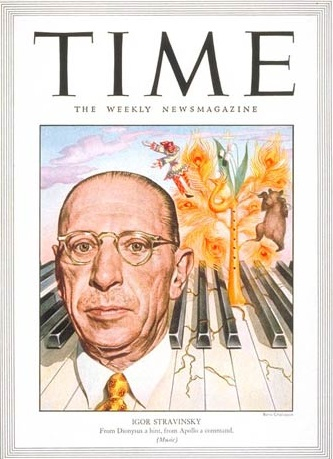

Igor Stravinsky, the Composer, Dead at 88

By DONAL HENAHAN

Igor Stravinsky, the composer whose "Le Sacre du Printemps" exploded in the face of the music world in 1913 and blew it into the 20th century, died of heart failure yesterday.

The Russian-born musician, 88 years old, had been in frail health for years but had been released from Lenox Hill Hospital in good condition only a week before his death, which came at 5:20 A.M. in his newly purchased apartment at 920 Fifth Avenue.

Stravinsky's power as a detonating force and his position as this century's most significant composer were summed up by Pierre Boulez, who becomes musical director of the New York Philharmonic next season:

"The death of Stravinsky means the final disappearance of a musical generation which gave music its basic shock at the beginning of this century and which brought about the real departure from Romanticism.

"Something radically new, even foreign to Western tradition, had to be found for music to survive, and to enter our contemporary era. The glory of Stravinsky was to have belonged to this extremely gifted generation and to be one of the most creative of them all."

George Balanchine, head of the New York City Ballet and a fellow Russian and longtime friend, said:

"I feel he is still with us. He has left us the treasures of his genius, which will live with us forever. We must have done 20 ballets together, and I hope to do more."

Planning began immediately for memorial programs. The New York Philharmonic, although unable to change its rehearsal schedules to include Stravinsky music this week, announced that the concerts would be dedicated to his memory. The New York City Opera dedicated last night's performance of "Don Rodrigo" to the composer.

With Stravinsky at his bedside were his wife, Vera; his musical assistant and close friend, Robert Craft; Lillian Libman, his personal manager, and his nurse, Rita Christiansen. Mr. Craft, according to Miss Libman, was too shaken by the death to speak to callers, but wished it known that he had "lost the dearest friend he ever had." Mr. Craft, who had been Arnold Schoenberg's secretary before that composer's death, went to work for Stravinsky in 1947.

The composer had returned in August, "much refreshed," after a vacation of two and a half months at Evian, France, Miss Libman said, but had entered Lenox Hill Hospital here with pulmonary edema on March 18. His stay there was extended somewhat, she said, because his new 10-room apartment overlooking Central Park was being decorated. He did not go home until March 30.

The last words Miss Libman could remember Stravinsky's saying, she said, were, "How lovely. This belongs to me, it is my home," as his nurse gave him a tour of the apartment in his wheelchair. The cosmopolitan musician, she said, had moved around the world so much--Russia, Paris, Hollywood, New York--that his yearning for a home had been strong.

Was Composing Recently

Stravinsky knew his friends to the last, according to Miss Libman. "Two and a half months ago he was playing the piano and composing--orchestrating two preludes from Bach's 'Well-Tempered Clavier,'" she said.

His death came as a surprise, since he apparently had rallied on Monday night from breathing complications that developed over the weekend. Dr. Theodore Lax, the composer's physician throughout his recent illness, was not present at the time of death. He arrived soon thereafter and ruled the cause as heart failure. Since 1967, Stravinsky had suffered several arterial strokes, Miss Libman said, and had been in and out of hospitals since then.

Besides his widow, Stravinsky is survived by a daughter, Mrs. Milena Marion of Los Angeles, and two sons, Soulima, a pianist and teacher who lives in Urbana, Ill., and Theodore, of Geneva.

The composer's body was taken to Frank E. Campbell's at Madison Avenue and 81st Street. A Russian Orthodox service will be held there Friday at 3 P.M., with the Rev. Alex Schmenin officiating.

Burial in Venice

In accordance with Stravinsky's wish, burial will be in Venice, in the Russian corner of the cemetery of San Michele. The composer had long been fond of the Italian city, where several of his works including "The Rake's Progress" were first performed, and where Diaghliev is buried. It was Diaghliev the Russian ballet impresario, who produced the first performance of "Le Sacre du Printemps" on May 29, 1913, thereby giving Stravinsky his chance to turn music upside down.

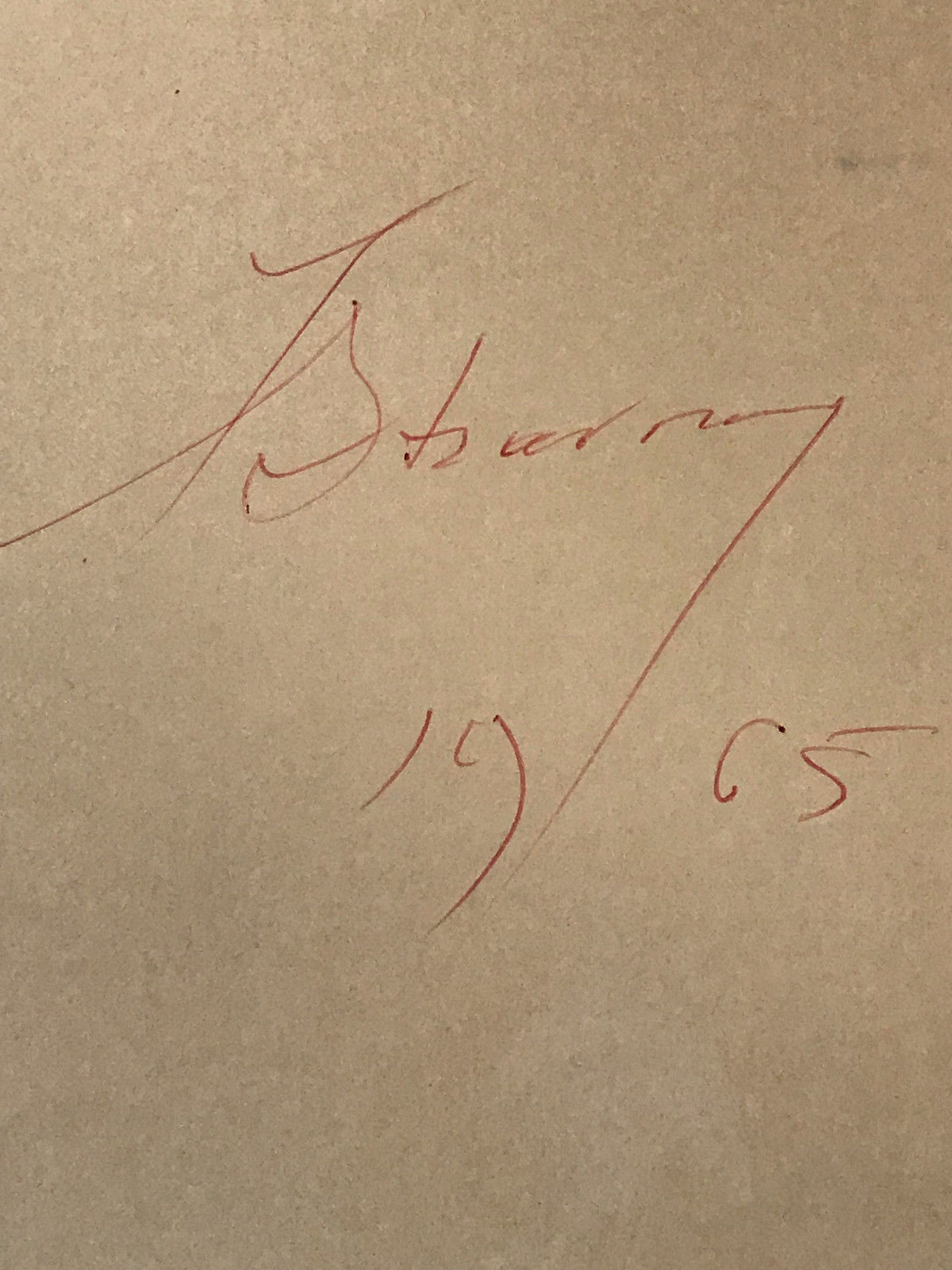

Stravinsky's more recent activities had been as a writer and dealer in his own memorabilia. The complete, corrected manuscript score of "Le Sacre," about 7,600 additional pages of manuscript and 17,000 documents were put on the market at an asking price of $3.5-million last December. No purchase has been reported.

In recent years, in spite of his feeble health, Mr. Stravinsky continued to be a fountain of wit and acidulously put wisdom. In an article in The New York Review of Books last February, he commented wryly on Leonard Bernstein's athletic podium style: "I have never seen him jump in 'Les Noces' and regretted missing his performance last fall."

Igor Stravinsky: An 'Inventor of Music' Whose Works Created a Revolution

During World I, Igor Stravinsky was asked by a guard at the French border to declare his profession. "An inventor of music," he said.

It was a typical Stravinsky remark: flat, self-assured, flagrantly antiromantic. The composer who revolutionized the music of his time was a dapper little man who prided himself on keeping "banker's hours" at his work table. Let others wait for artistic inspiration; what inspired Igor Stravinsky, he said, was the "exact requirements" of the next work.

Between the early pieces, written under the eye of his only teacher, Nikolai Rimsky- Korsakov, and the compositions of Stravinsky's old age, there were more than 100 works: symphonies, concertos, chamber pieces, songs, piano sonatas, operas and, above all, ballets.

The influence of these works was profound. As early as 1913, Claude Debussy was praising Stravinsky for having "enlarged the boundaries of the permissible" in music. Forty years later, the tribute of Lincoln Kirstein, director of the New York City Ballet, was remarkably similar: "Sounds he has found or invented, however strange or forbidding at the outset, have become domesticated in our ears."

Aaron Copland estimated that Stravinsky's work had influenced three generations of American composers; a decade later Copland revised the estimate to four generations, and added European composers as well. In 1965 the American Musicological Society voted Stravinsky the composer born after 1870 who was most likely to be honored in the future.

He was not unanimously honored during his lifetime. Three colorful works of his young manhood--"L'Oiseau de Feu" ("The Firebird"), "Petrushka" and "Le Sacre du Printemps" ("The Rite of Spring")--were generally admitted to be masterpieces.

But about his conversion to the austerities of neoclassicism in the nineteen-twenties, and his even more startling conversion to a cryptic serial style in the nineteen-fifties, there was critical disagreement. To some, his later works were thin and bloodless; to others, they showed a mastery only hinted at in the vivid early pieces.

Figure of Fascination

To all, Stravinsky the man was a figure of fascination. The contradictions were dazzling. The composer marched through a long career with the self-assurance of a Wagner--and was so nervous when performing in public that he thrice forgot his own piano concerto.

He once refused to compose a liturgical ballet for his earliest patron, Serge Diaghliev, "both because I disapproved of the idea of presenting the mass as a ballet spectacle and because Diaghliev wanted me to compose it and 'Les Noces' for the same price."

His Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard in 1939-40 were dignified papers, delivered in French, on the high seriousness of the artist's calling. Three years later he wrote a polka for an elephant in the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus.

He had many friends--Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Pablo Picasso, Vaslav Nijinsky, Andre Gide, Jean Cocteau--and many homes: Russia until 1914; Switzerland (1914- 1920), France (1920-1939), the United States (1939 until his death). In every home he was restless at night unless a light burned outside his bedroom. That was how he slept, he explained, as a boy in St. Petersburg (now Leningrad).

Igor Feodorovich Stravinsky was born in a suburb of St. Petersburg--Oranienbaum, a village where his parents were spending the summer--on June 17, 1882: St. Igor's Day. He was the third of four sons born to Anna Kholodovsky and Feodor Ignatievitch Stravinsky. His father was the leading bass singer at the Imperial Opera in St. Petersburg.

The composer once described his childhood as "a period waiting for the moment when I could send everyone and everything connected with it to hell." For his family he felt only "duties." At school he made few friends and proved only a mediocre student.

Music was a bright spot. At the age of 2 he surprised his parents by humming from memory a folk tune he had heard some women singing.

He dated his career as a composer from the afternoon a few years later when he tried to duplicate on one of the two grand pianos in the family's drawing room the blare of a marine band playing outside.

"I tried to pick out the intervals I had heard. . .but found other intervals in the process I liked better, which already made me a composer," Stravinsky said.

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson