My Grandfather Richard Rodgers by Peter Melnick

Published in the May-June 2019 issue of The Dramatist

As a Rodgers grandson who happens also to be a composer, I read Todd S. Purdum’s 2018 book, Something Wonderful: Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Broadway Revolution, with more than casual interest. Purdum, at the time a national editor and political correspondent for Vanity Fair, took a sabbatical from his regular beat to write about a subject he loves, and a pair of musical theater gods for whom he clearly has enormous affection. His was the first book on my grandfather to receive significant media attention since the publication of Meryle Secrest’s much darker biography, Somewhere For Me, in late 2001. In her acknowledgments, Secrest explained that she wrote the bookat the invitation of my aunt, Mary Rodgers Guettel, whom she described as “frank, funny, and very sympathique, with a special kind of strength that comes from surmounting the handicap of parents who do not necessarily see candor as a virtue.”

In December 1979, I was a 21-year-old, present in my grandparents’ New York apartment on the night my grandfather died. He was just 77. Later that evening, I found myself alone with Mary, and was witness to a twilight zone eruption of pain and loss in her. It was as though someone had proclaimed, les jeux sont faits, and the finality of her father’s death exposed a deep hurt that for my aunt had suddenly become irrevocable. Talking more to herself than to me, she exploded with an anger that was at once histrionic and true.

To a large extent, the Secrest biography reflects my aunt’s experiences, expressing a hurt that, if anything, seemed to become more inflamed in the years following her parents’ deaths. Mary came by her pain honestly, but hers was a deeply personal perspective. The resulting book portrays a Dick Rodgers who was gifted but miserable, an alcoholic and a womanizer, someone who was miserly with both his money and his affections. Dorothy Rodgers, my grandmother, fared even less well by Secrest. She appeared to be a patchwork of cold, self-deluding traits, a true monster straight out of the National Enquirer–a caricature of the grandmother I knew. The Secrest biography is akin to telling the story of King Lear through the eyes of Regan or Goneril, as librettist Sherman Yellen, one of my grandparents’ few living friends, observed. I might enjoy reading that version of Lear, but as a work of literary fiction, not biography.

Todd Purdum’s book is different, a useful exploration of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s transformative impact on musical theater. When he writes about Rodgers the man, however, he’s still operating within the confines of Secrest’s narrative. He quotes Stephen Sondheim’s famous dictum that my grandfather had “infinite talent but limited soul,” and then turns to costume designer Lucinda Ballard, who states, “Dick loved money more than anybody I’ve ever seen, except Oscar… And yet, Oscar was the most lovable person I almost ever knew, and Dick really was not.”

There’s something about these two quotes that discourages any impulse to understand the man behind the music. They are opinions, but in Purdum’s book they have the weight and feel of truth, reinforcing the conventional wisdom that Richard Rodgers was “the keenest of businessmen,” who just happened to write extraordinary music. It’s as though Purdum were describing an ordinary American sedan, equipped with a Ferrari engine, without actually looking under the hood or asking the question, “Say, what’s that old sedan doing with a Ferrari engine, anyway?”

From where I sit, the Sondheim quote sounds better than it is. Personally, I don’t get the concept of a “limited soul,” but if souls can be measured, my grandfather’s must be an Extra Large. The proof is in the music itself. Take the title song from The Sound of Music, and listen to the way Poppa (Mr. Rodgers to you) set the first line of Oscar’s refrain –“The hills are alive with the sound of music.” Feel the changing harmony on the word “music,” and the spot in the last verse–“I go to the hills when my heart is lonely” –where that same harmonic shift occurs. When the chords change on the words “music” and “lonely,” the lovely world established by the melody up to that point cracks open, revealing a depth of feeling that is sublime, truly beyond description. Where does that come from? It’s beautiful from God. Not pretty from central casting.

For me, there is a special poignancy to this song. Rodgers and Hammerstein wrote it in the spring of 1959. Oscar would not receive his diagnosis of stomach cancer until that fall, so neither man was aware of the devastating news to come. Still, the two were writing on either side of age sixty, and sixty was a lot older in 1959 than it is today. Those hills were the place where Poppa truly breathed, where he found joy. And Oscar was the partner with whom, for nearly twenty years, he breathed the best. When I think of the final quatrain, I think not of Maria, the character who sings it, but of Poppa himself:

I go to the hills when my heart is lonely

I know I will hear what I’ve heard before

My heart will be blessed with the sound of music

And I’ll sing once more

My grandfather occupies a very important place in my life, both the man and his music. As a composer, I know something about the emotional places he visited when he went to those hills. I also try to understand what it was like to be him the rest of the time, the way he inhabited the part of his life not spent composing. When I was little, I thought about him almost as though he were two distinct people –my flesh-and-blood grandfather whom I called Poppa, and the quadrisyllabic entity, Richard-Rodgers, whom I wasn’t supposed to talk about outside of the family because he was famous and it’s not nice to boast. As an adult grandchild, it’s become important to me to try to fathom the relationship between the man and the extraordinary music he wrote.

Poppa was 56 when I was born, but by the time I was sentient, he was already engaged in a rapid descent into old age. During the course of our shared 21 years, his stride grew ever shorter, becoming a slow shuffle by the time he reached his mid-seventies. My other grandfather died long before I was born, so when I was little, Poppa represented everything I knew about grandfathers. As far as I could tell, they were the ones who played hand games with you at the table, cupping your tiny paws inside one of their much larger ones, and who let you watch as they shaved with an electric razor, permitting you a before-and-after stroke of their cheeks so that you could feel them changing from scratchy-tickly to incredibly soft.

It turned out that grandfathers were also the ones who wrote music. I heard Poppa’s everywhere –when I rode the carousel in Central Park, in elevators and, of course, on Broadway. (My first theater experience was a matinee of The Sound of Music, during the show’s original run, when I was three. At the intermission, my mother, Linda Rodgers Emory, clapped her hands together enthusiastically and said, “Wasn’t that terrific!” I happily agreed, and followed her out of the theater, unaware that there was a second act, in which the Nazis got a whole lot nazi-er.)

Above all else, I heard Poppa’s music at home. When my mother played “In My Own Little Corner” from Cinderella on the family Steinway, she was playing our song, a secret proof against childhood loneliness. Even today, I often experience my grandfather’s music as a direct pipeline to a place very pure and magical, the best part of my youth.

When I spent time with my grandfather, I wasn’t thinking about his music. I just liked the grandfatherly things he did with me, like the day he got me past my fear of dogs. I was four years old at the time, spending the weekend at Rockmeadow, my grandparents’ home in Westport, Connecticut. When my mother was a child, they used to keep standard poodles, all with Gilbert and Sullivan-inspired names, like Penny and Pi. By the time I came along, they had switched breeds. My starter dogs were two extremely docile Irish setters named Bridie and Sean. That Sunday, Poppa took me out in front of the house, and spent the better part of an hour patiently easing me past my fear, working up to the big moment when I felt safe enough to pet Bridie’s sleek fur and let her lick my hand.

Unfortunately, the moment didn’t last. It had been roughly a year since Oscar Hammerstein’s death, and our Rockmeadow weekend took place at a time when Poppa and Alan Jay Lerner were exploring the possibility of writing a show together. Lerner was meant to come to dinner that Friday night, but he called at the last minute, rescheduling for Saturday lunch. Saturday morning rolled around, and he called again; he was coming from Long Island, and the traffic was monstrous. New plan: he would boat across Long Island Sound, and arrive in time for dinner. My grandmother must have been ready to kill him, especially when Saturday night also proved unworkable. In the end, Lerner arrived by car, pulling up late Sunday morning just as Poppa and I were finishing up with Bridie and Sean.

Poppa introduced us, and I was about to shake Lerner’s hand when I noticed the tips of his fingers, all covered in bandages. “What’re they for?” I asked. Lerner didn’t want to say the real reason –that he bit his nails down to the quick, and they had become infected –so he improvised. “Oh, a dog bit me,” he said. There were other, more substantive reasons why the Lerner and Rodgers collaboration never happened, but I suspect I was present for the coup de grâce.

I can recall only one time when Poppa got angry with me. It was the fall of 1970, when I was twelve. I flew with my grandmother to Boston, where Two By Two, Poppa’s musical about Noah and his ark, was in previews. I remember standing with him at the back of the Shubert Theatre, watching a matinee together. Afterward he asked me questions about what I liked, and we talked about what was working, and what needed work. I was thrilled.

That night we ate at Locke-Obers, a restaurant in Boston’s theater district that dates back to the early 19th century. There were five or six of us at the table, and at some point the conversation turned to Joshua Logan, director of South Pacific and the Rodgers and Hart show, By Jupiter. Logan also directed the subsequent film of South Pacific, for which he employed the innovation of shooting many of the production numbers through color filters that he hoped would have a subtle emotional impact on these scenes. Unfortunately, the end result was neither subtle nor well-received, and Logan, who suffered from bi-polar disorder, took a lot of heat for his idea. I must have heard about this episode, because I made some sort of smart-a** comment, deriding Logan’s flight of fancy.

Poppa cut me off, his displeasure an expression of loyalty to the man I had casually disparaged. I had never seen that side of Poppa before, and knew that I had spoken out of turn. But his anger was moderate, not shaming, and it left room for other thoughts to seep in –the sudden discovery that I respected my grandfather, and the realization that I had never stopped to ask myself who he really was. Up until then, Poppa had been an agreeable presence in my life, someone I took for granted, like a big oak tree in the back yard. It was a revelation to discover that there were things that mattered to him, beyond being a grandfather and a composer. At the age of twelve I discovered that my grandfather was actually a person, not a tree.

Poppa was just 17 when he and Lorenz Hart had their first frisson of success, a song called “Any Old Place with You” (source of the famous Hart couplet, “I’d go to hell for ya, or Philadelphia”). Over the next few years, they honed their craft, writing upwards of 60 songs and a string of shows that, for the most part, came and went without making much of a splash. But when an invitation came to Rodgers and Hart in 1926 to contribute a few songs to a Theater Guild benefit show, “Manhattan” electrified the audience and become their first bone fide hit.

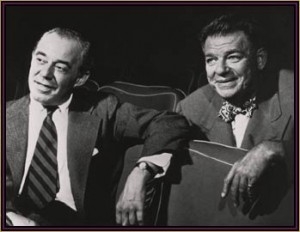

After that, Rodgers and Hart took off. Their output was staggering. Between Broadway and the West End they wrote or contributed to roughly thirty shows and a dozen film musicals, their songs largely defining the American songbook–“Blue Moon,” “My Romance,” “My Funny Valentine,” “Falling in Love With Love,” “Ten Cents a Dance,” “Easy to Remember,” “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” and many others.

There was an energetic, fun quality to my grandfather in the early years of his career. By the time he teamed up with Oscar Hammerstein to write their first show, Oklahoma!, however, all that insouciance had seemingly vanished. To some extent the change was perceptual –call it the intimidation factor. Think John, Paul, George and Ringo circa Hamburg, compared to the post-touring Beatles on the cusp of recording Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and you get maybe a hint of the enormity of the transformation. When the Beatles gave up touring in mid-1966, they had long since left behind the playful personas they projected in A Hard Day’s Night and Help! As a studio band they reached new, formidable levels of creativity. The business of being The Beatles also took on more weight. Two years after they stopped touring, they formed Apple Records, and created an empire. They were huge, larger than life. Like Rodgers and Hammerstein.You might have liked to drink a beer with Paul McCartney in some Reeperbahn dive in Hamburg. But the McCartney revealed in Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s Let It Be documentary was scary talented and intimidating, even to his fellow Beatles.

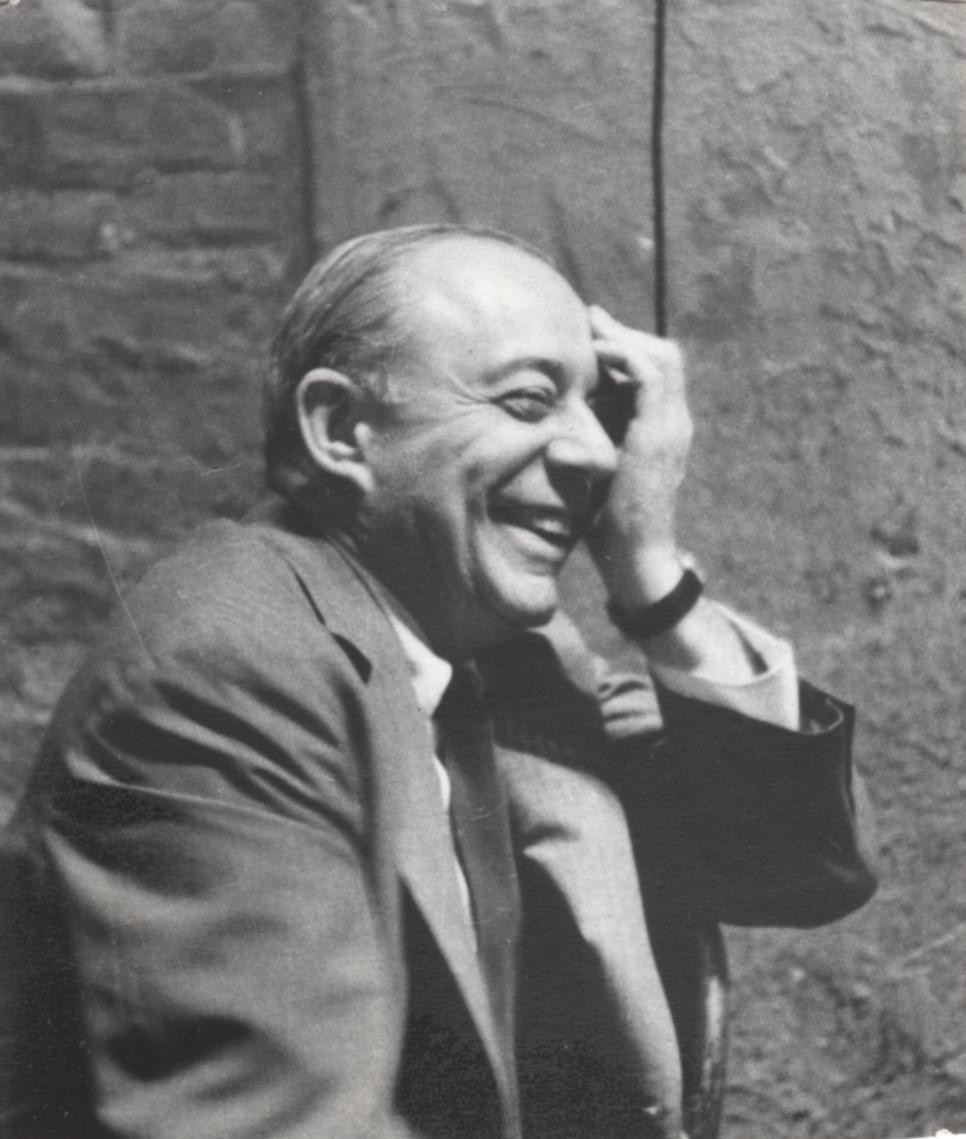

Richard Rodgers laughing

The theatrical entity Rodgers & Hammerstein was indeed serious business, and the scope and complexity of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s shows required something different from just about anything that had gone on before. Already seasoned pros, they were savvy enough to understand the need for a sophisticated approach to the evolving business. Of necessity, they became pioneers, developing new business structures capable of capitalizing on increasingly complex royalty streams. There was an inherent tension in the fact that they were now wearing two hats. When the other members of their creative teams collaborated with themas authors, they were also interfacing with the show’s producers in a way that was unique. Authors can be dreamers, but a show’s producers make difficult, sometimes unpopular decisions on a daily basis. It’s hardly surprising that they were sometimes resented.

There were other, more personal reasons why my grandfather entered his second act a man apart. Larry Hart’s binge drinking had become increasingly severe during the 1930s, and the last years of their partnership were challenging.Even as they collaborated on their last and arguably most successful shows –Boys From Syracuse, Pal Joey and By Jupiter–Hart was on a downward spiral of end-stage alcoholism,Poppa riding shotgun on that harrowing journey. (Having lost my own father to addiction, I have some inkling of how brutal those years must have been for Poppa –little else in my life ever approached that level of pain and helplessness.) When Hart died in 1943, barely a month after Oklahoma! opened, my grandfather lost both a dear friend and the partner to whom his fortunes were tethered.

My grandfather also struggled with alcoholism throughout his life, and intense depression. As early as January 1928, he wrote about it with astonishing openness in a letter to my grandmother:

Three times now since I left home I’ve experienced something I’ve never known before, and tonight is the third. I have an active and intense feeling of depression which is absolutely impossible to shake off… I need something very badly and I don’t know what it is. Please don’t’ think I’m crazy…

The library at Lincoln Center houses some 350 letters my grandfather wrote to my grandmother over the five decades spanning from the mid-1920s through 1974. Depression figures prominently in many of them, Poppa writing from deep inside the experience, with an eloquence that was visceral, not writerly. Another letter, written in August 1930 from aboard the S.S. Olympic en route to London for rehearsals of a new show, includes the following:

…I’d give my soul to have you in this room at this moment. Then I’d feel safe. As it is, I’m afraid! I’m not afraid of the work, or people… but (I’m writing now after four double brandies…) I’m afraid of something that’s raising hell with me. I want to yell because I feel strong and I want terribly to feel that surge when you and I are close together. Baby, at the same time I know logically that I shouldn’t be writing to you this way; that you’ll worry. What can I do? I can’t tell anybody here. You’re the only person in the world that I could ever tell the whole truth to. Look, Angel, I am telling it to you now, and I don’t care…

He then confided that he was also struggling with urges of infidelity, declaring his resolve not to give in. The letter concluded with the urgent request, “Will you please, please remember what I tried to say when we said our goodbyes? I’ve never loved anyone but you, and I swear it, I never will.”

This letter floors me. It expresses a tidal wave of pain and confusion. But also, it’s a love song, conveying a powerful need to be known by my grandmother. Indeed, the huge surprise of these letters is what they convey about the depths and complexity of Poppa’s feelings for my grandmother. There’s tenderness, and a sense of yearning, in nearly all of them. “You know what I miss terribly?” he wrote in September 1930. “Waking up in the morning and kissing your hand… I’ve discovered that going to bed alone is actually not so displeasing as waking up that way…”Nearly three decades later, around the time he was composing the score to The Sound of Music, he wrote:

It was so good to hear your voice this morning; you sounded so well and happy.I loved your note with all the “I love you’s.” This is my one chance to write you and say the same. I miss you so much! The apartment is so empty and so am I…

Come home!

I love you.

R.

It’s clear to me that my grandfather loved my grandmother to the end of his days. The letters also strongly support the idea that my grandparents’ marriage was profoundly co-dependent. My grandmother’s tremendous unhappiness is unmistakable, even from Poppa’s side of the correspondence. The flip side –his desperate need to please her–is equally evident.“…my angel, don’t be so sad,” he wrote from London, where he was attending rehearsals while she remained behind in New York, five months into a difficult pregnancy. “I love you so much that it kills me to have you cry when I can’t put my arms around you…” And a week after that:

Two letters came from you this morning, both filled with unhappiness, fretting and dissatisfaction. I leave it to you to picture the frame of mind in which such letters leave me…Oh, Darling! If only your letters weren’t always trying to beat me down and telling me how awful it is of me to be away. I’m sure you don’t know what you’ve written –it’s so cruel…

It’s no coincidence that his episodes of depression frequently emerged during their time apart. It may also be significant that several of his most serious health crises occurred while she was away. My belief is that the intensity of his love for her was so much greater than his need for anyone else that, when they were apart, there was a great hole inside him, and his depression took over. He needed her good graces, and he could not keep her happy –that was also part of the co-dependency. The best he could do was to show her that nobody else was as important to him.

The conventional wisdom is that, someplace along the way, the marriage of Dick and Dorothy Rodgers evolved into an arrangement, my grandfather ceding control over just about everything to Dorothy in exchange for an inviolable right to disappear into his work. According to this orthodoxy, Poppa willingly gave short shrift to everyone and everything else in his life in pursuit of the joy he found in his work; Richard Rodgers the composer thrived, and the emotional life of his family, my family, paid a steep price.

The trouble with this conventional wisdom is that it bears only a wax-museum resemblance to my grandparents’ actual lives and the complexities of their marriage. It fails to address my grandfather’s drinking, and the huge shadow that depression must have cast over both of their lives. (Dorothy Rodgers’ father also suffered from profound depression. When he fell from the terrace of his Manhattan apartment in late 1931, a probable suicide, my grandmother could not have ignored the danger depression posed to her own marriage as well.)If Poppa sold his family short, it was not the result of a Faustian bargain in pursuit of musical theater success. He was lunging for sanctuary from whatever it was that was raising so much hell within him. And my grandmother was right there alongside him, battening down the hatches in the effort to keep peril at bay.

It is perhaps not surprising that my mother also lived with depression, undiagnosed until she was well into her fifties. She worked hard in later years to make sense of her life, and came to view her father with enormous compassion. Mom told Secrest that her parents “needed and supported each other and were the worst people in the world for each other.” She felt her father loved her“when he was able to, but that wasn’t very often… He had all he could do to take care of himself, and there wasn’t much left over.”

Writing this article has truly been a labor of love, affording me a view of my grandfather, perhaps for the first time, as a full human being. His great sense of humor and a surprising capacity for fun –traits I heard about but could not discern when I spent time with him–come across in nearly all of his archived letters. I discovered, too, the heart of a loving grandfather who was at pains to check in on my cousins and me whenever our grandmother was out of town. On one such occasion, when I was a mere two months old, he wrote, “I talked with all the grandchildren except Peter, for some reason, and found them all delightfully unintelligible as of this rainy morning…” A few days later he paid me an actual house call, and reported back to Granny, “Peter is wonderful and wants to know can he smoke?”

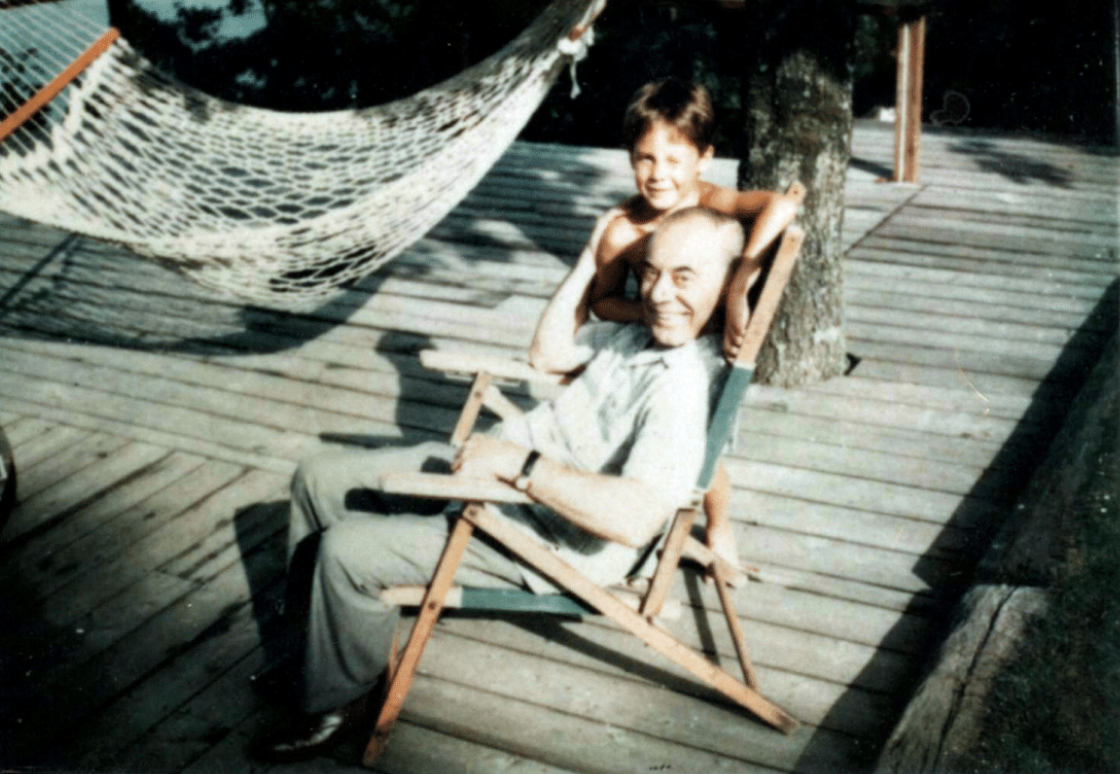

Peter Melnick and Richard Rodgers, 1964

Perhaps even more than the average bear, my grandfather was a very complex person –funny and smart and wounded and sweet and loving and, not for nothing, one of the most extraordinary composers of all time. There’s no question that he lived with, and passed on, much damage. I had a ringside seat to some of it and, sorry to say, so have my kids. But unlike Poppa, we are fortunate, blessed even, to live in an era with much to offer in the way of healing. I don’t think that my grandfather ever made it far in the direction of healing. In light of all the joy he brought to the world through his music, there’s something deeply poignant about that.

One day, someone will come along with the ambition to write the next Richard Rodgers biography. I hope they bring honesty and compassion to their work. Certainly, they should go after their quarry armed for bear. But I hope he or she thinks to bring along a butterfly net as well, or perhaps even a dreamcatcher. How else do you hold a moonbeam in your hand?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson