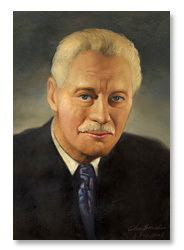

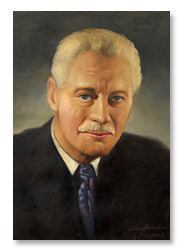

Article Image

Robert Russell Bennett (1894-1981) was lucky enough to have worked during that golden era of Broadway musicals when the credit "orchestrated by" implied an actual orchestra in the theatre. Oh, we still have wonderful music on Broadway, and Broadway producers still regularly engage skillful, even inspired orchestrators, but what these orchestrators have to work with hardly compares to the symphonette that once filled the space between the front row and the proscenium arch. Today's orchestrators often have to make do with a rhythm combo, a couple of woodwinds, an occasional French horn or a cello, and all too frequently a computer to help convince the audience they're hearing something more.

Join Backstage to access jobs you can apply to right now!

In the theatre, the orchestrator is, quite simply, the other dramatist in the room. He is telling the story with an orchestra. And for much of the 20th century, nobody did it better than Bennett. What does an orchestrator do? He or she takes the music the composer has written, usually on a piano, and imagines it being played by, for example, violins, trumpets, and drums. Then the orchestrator writes down those imaginings on a piece of score paper. He or she may hear a cheerful figure that should be played by a flute while trombones play the melody, or sense when the after-beats should be played by a snare drum (because the singing is powerful) or by the violas (because the singing is quieter).

When the music sounds (or needs to sound) sinister, the orchestrator makes a note to accompany it with a quirky bassoon or an English horn. He or she knows how to use that same bassoon or English horn to point up something comical or to break your heart. When Bennett was a boy, his father had a touring band. Whenever one of the players was unavailable, Bennett would substitute for him. He therefore acquired at an early age a hands-on understanding not only of how different instruments are played, but how to deploy their unique sounds into seemingly endless combinations of musical and emotional shades and hues.

After formal training in Paris, Bennett moved to New York, where he worked as a copyist and created dance band arrangements for the reigning popular composers of the day. Broadway seemed an unlikely home for the classically trained, high-minded young man, but his gifts soon took him from the work he was doing to improving the work being done by others. He moved from doctoring the shows of his peers to becoming the principal orchestrator for a stunning list of Broadway musicals, operas, and operettas — a list that reads like the history of the musical theatre itself: Rose Marie (1924), Lady, Be Good (1924), No, No, Nanette (1925), Show Boat (1927), Girl Crazy (1930), Of Thee I Sing (1931), Anything Goes (1934), Du Barry Was a Lady (1939), Carmen Jones (1943), Oklahoma! (1943), Carousel (1945), Annie Get Your Gun (1946), Finian's Rainbow (1947), Kiss Me, Kate (1948), South Pacific (1949), The King and I (1951), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1951), Bells Are Ringing (1956), Flower Drum Song (1958), The Sound of Music (1959), and On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (1965). The list also includes, in collaboration with Philip J. Lang, My Fair Lady (1956) and Camelot (1961) — more than 300 shows in all.

Along the way, Bennett's "serious" side included composing symphonies, concertos, sonatas, and operas. He also worked on movies (Swing Time, Shall We Dance, Lady in the Dark, Oklahoma!) and TV programs (Richard Rodgers' 13-hour score for Victory at Sea) and won an Emmy, a Grammy, and an Oscar.

Bennett was the dean, the guy you went to first, because he was the musician's musician. His technique was impeccable, his instincts flawless. He understood more and was able to communicate and navigate further and with greater success than any orchestrator who came before him. Bennett understood sound — acoustic sound as well as the manufactured kind. He could walk through an empty theatre just snapping his fingers to get the feel of the room. Out of town, his orchestrations sometimes had to be temporarily modified, but once the show moved into the theatre for which it was designed, the sonics of the orchestra were perfect. Audiences could hear every lyric as well as the harp obbligato undulating beneath it. When Gertrude Lawrence's ebbing voice required additional melodic support for her songs in The King and I, Bennett actually moved the melody from instrument to instrument, following her as she crossed the stage. When a composer or director said, "Russell, I don't know what it is, but something is not right," Bennett knew what it was and fixed it.

By the time Bennett died — his last Broadway orchestrating credit was for a single song in 1971's The Grass Harp — a full Broadway pit orchestra was becoming a rarity. Today's orchestrators must cope with critically reduced resources. Sometimes this is fine: The solo piano and harp for The Fantasticks doesn't disappoint (even though Jonathan Tunick's full orchestration for the film version is what composer Harvey Schmidt says he had always hoped for). And we don't need a substantial string section to enjoy Avenue Q.

But if you want to experience who Bennett was and what he did, feel the electric thrill of the audience at the Lincoln Center Theater revival of South Pacific. There, a 30-piece orchestra in the pit plays Bennett's original orchestrations as they were first heard in 1949. But you'll not only hear how truly golden that legendary era of Broadway musicals was. You'll understand what Bennett did to make it so and how wonderful the musical theatre was when he was doing it.

Bruce Pomahac is the director of music for the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization.

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson