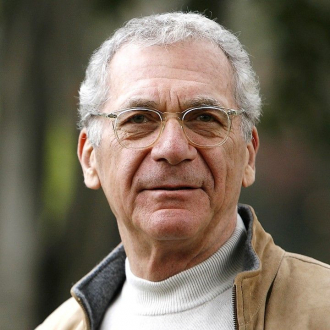

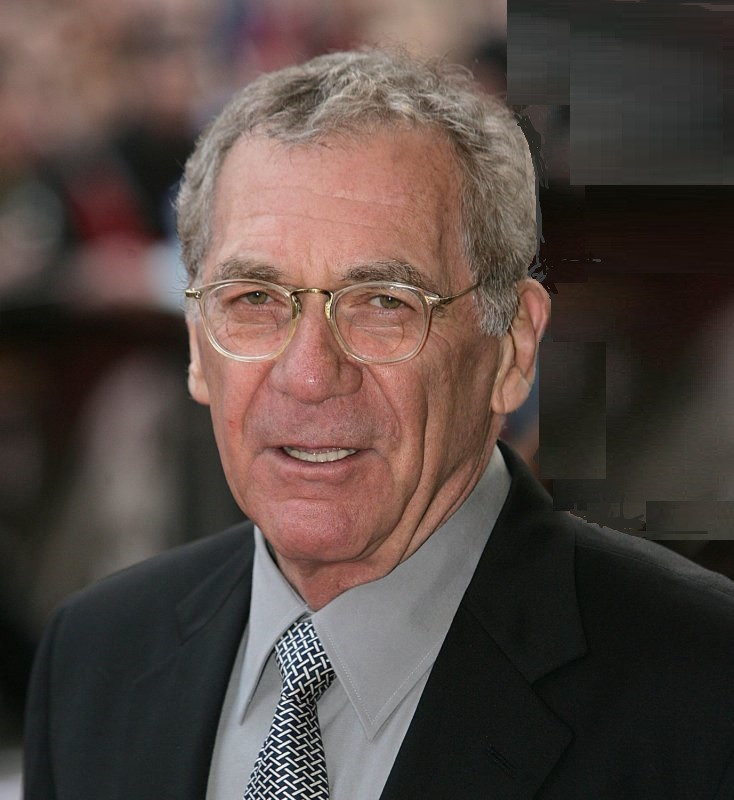

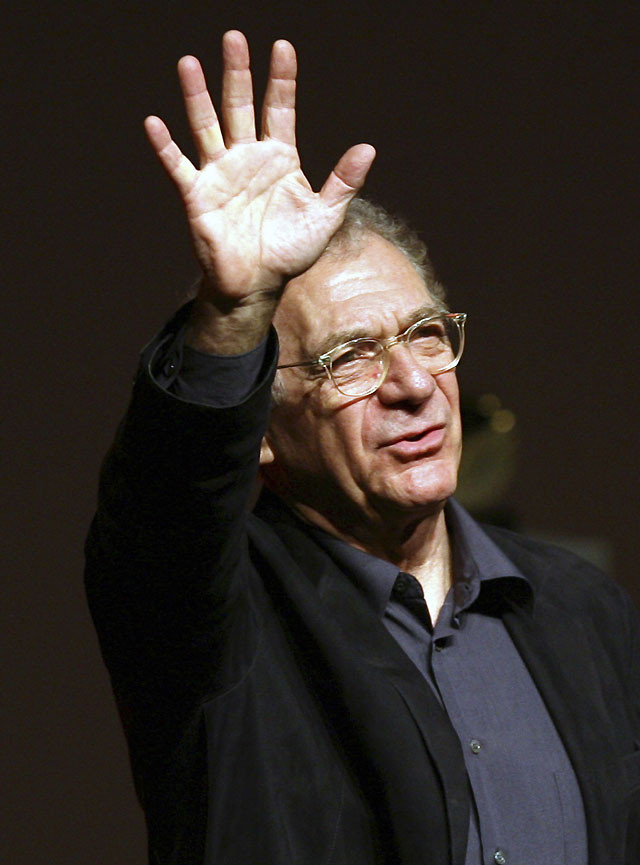

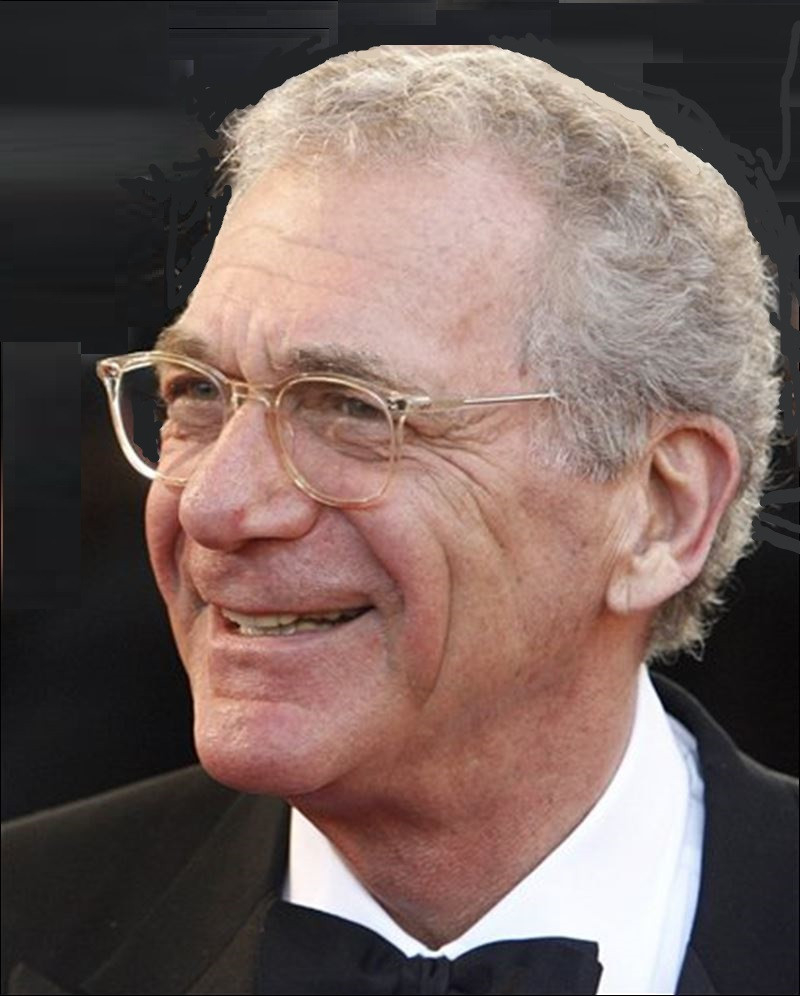

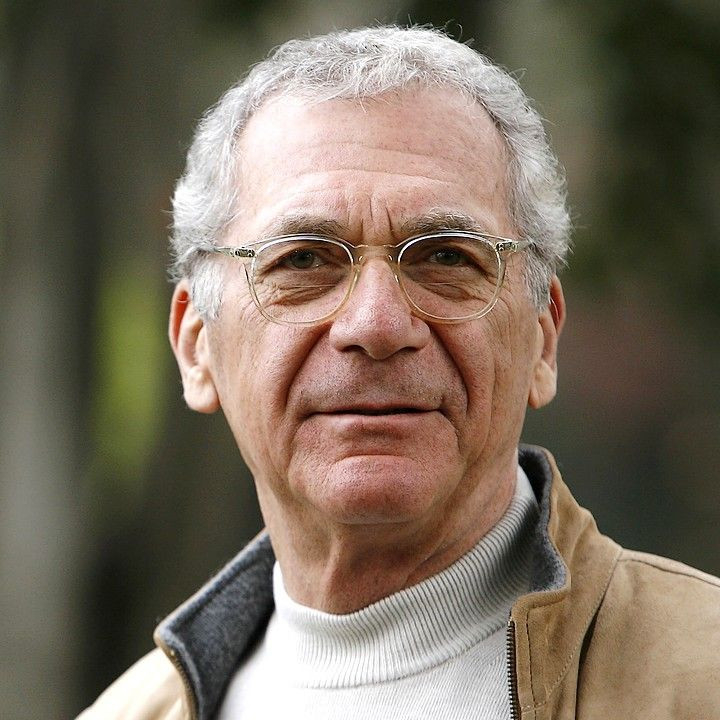

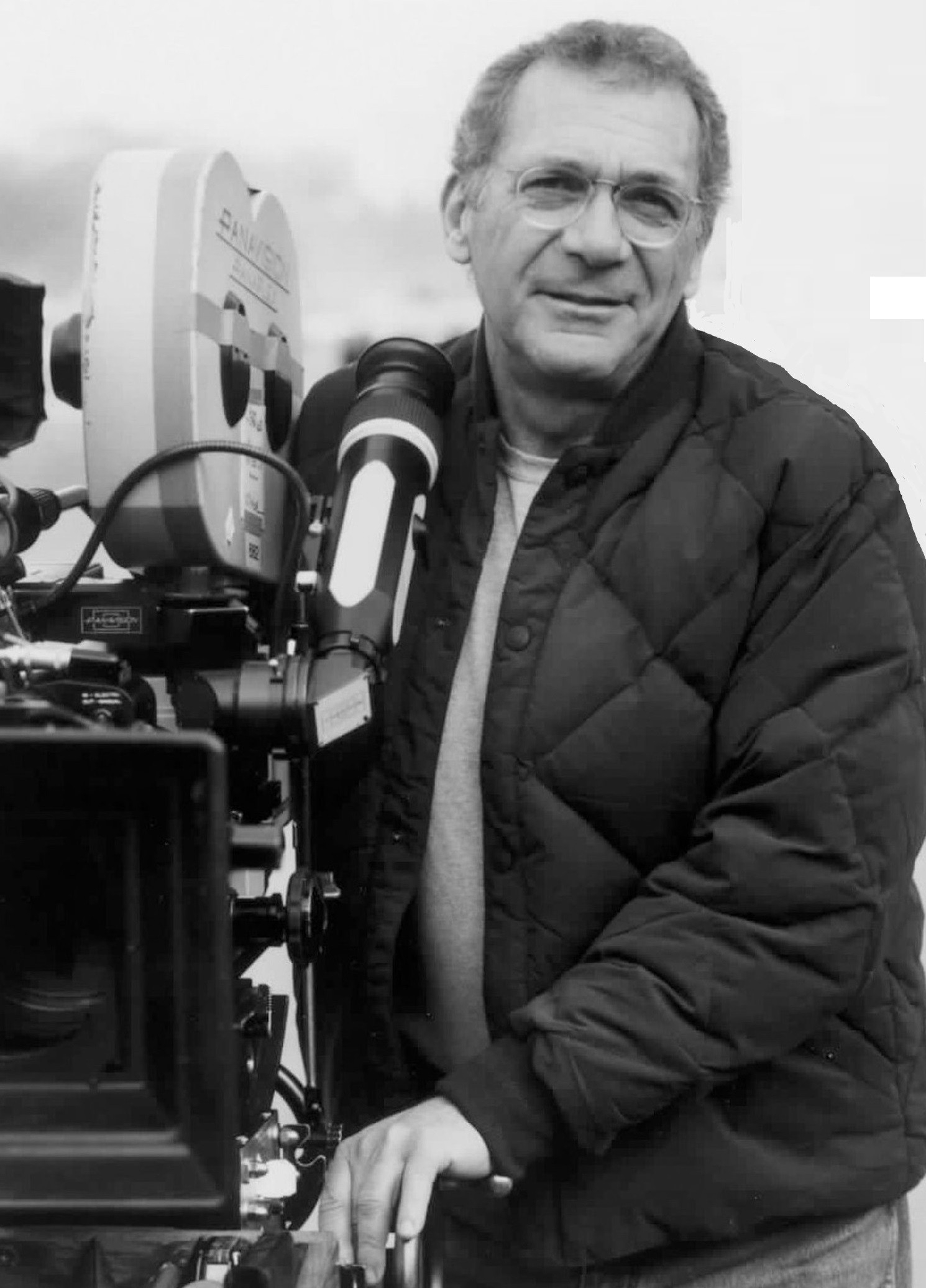

Sydney Pollack

Biography

Showing all 66 items

Jump to: Overview (4) | Mini Bio (1) | Family (4) | Trade Mark (1) | Trivia (27) | Personal Quotes (29)

Overview (4)

Born July 1, 1934 in Lafayette, Indiana, USA

Died May 26, 2008 in Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, California, USA (stomach cancer)

Birth Name Sydney Irwin Pollack

Height 5' 11½" (1.82 m)

Mini Bio (1)

Sydney Pollack was an Academy Award-winning director, producer, actor, writer and public figure, who directed and produced over 40 films.

Sydney Irwin Pollack was born July 1, 1934 in Lafayette, Indiana, USA, to Rebecca (Miller), a homemaker, and David Pollack, a professional boxer turned pharmacist. All of his grandparents were Russian Jewish immigrants. His parents divorced when he was young. His mother, an alcoholic, died at age 37, when Sydney was 16. He spent his formative years in Indiana, graduating from his HS in 1952, then moved to New York City.

From 1952-1954 young Pollack studied acting with Sanford Meisner at The Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre in New York. He served two years in the army and then returned to the Neighborhood Playhouse and taught acting. In 1958, Pollack married his former student Claire Griswold. They had three children. Their son, Steven Pollack, died in a plane crash on November 26, 1993, in Santa Monica, California. Their daughter, Rebecca Pollack, served as vice president of film production at United Artists during the 1990s. Their youngest daughter, Rachel Pollack, was born in 1969.

Pollack began acting on stage, then became a television director in the early 1960s. He made his big-screen acting debut in War Hunt (1962), where he met fellow actor Robert Redford, and the two co-stars established a life-long friendship. Pollack called on his good friend Redford to play opposite Natalie Wood in This Property Is Condemned (1966). Pollack and Redford worked together on six more films over the years. His biggest success came with Out of Africa (1985), starring Robert Redford and Meryl Streep. The movie earned eleven Academy Award nominations in all and seven wins, including Pollack's two Oscars: one for Best Direction and one for Best Picture.

Pollack showed his best as a comedy director and actor in Tootsie (1982), where he brought feminist issues to public awareness using his remarkable wit and wisdom and created a highly entertaining film that was nominated for ten Academy Awards. Pollack's directing revealed Dustin Hoffman's range and nuanced acting in gender switching from a dominant boyfriend to a nurse in drag, a brilliant collaboration of director and actor that broadened public perception about sex roles. Pollack also made success in producing such films as The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999), The Quiet American (2002), and Cold Mountain (2003). Pollack returned to the director's chair in 2004 when he directed The Interpreter (2005), the first film ever shot on location at the United Nations Headquarters and within the General Assembly in New York City.

In 2000, Sydney Pollack was honored with the John Huston Award from the Directors Guild of America as a "defender of artists' rights." He died from cancer on May 26, 2008, at his home in the Los Angeles suburb of Pacific Palisades, California.

- IMDb Mini Biography By: Steve Shelokhonov

Family (4)

Spouse Claire Griswold (22 September 1958 - 26 May 2008) (his death) (3 children)

Children Steven Sanford Pollack

Rebecca Pollack

Rachel Pollack

Parents Rebecca Pollack

David Pollack

Relatives Bernie Pollack (sibling)

Shawn Griffith (niece or nephew)

Trade Mark (1)

Frequently casts Robert Redford

Trivia (27)

He brought a lawsuit against Danish TV after screening Three Days of the Condor (1975) in pan-and-scan in 1991. (April 1997) The court ruled that the pan scanning conducted by Danish television was a 'mutilation' of the film Three Days of the Condor (1975) and a violation of Pollack's 'Droit Moral,' his legal right as an artist to maintain his reputation by protecting the integrity of his work. Nonetheless, the court ruled in favor of the defendant on a technicality. [January 1997]

Brother of Bernie Pollack

Winner of the year 2000 John Huston Award, presented by Tom Cruise on behalf of the Directors Guild of America, as a "defender of artists' rights...a warrior."

Among the 100 best American love movies ranked by American Film Institute in June 2002, Pollack is the only director credited with two films near the top of list. His The Way We Were (1973) is ranked #6 and Out of Africa (1985) is ranked #13.

Three children: a son, Steven Pollack, born in 1959 (died 1993); daughter, Rebecca Pollack, born in 1964; daughter, Rachel Pollack, born in 1969.

Pollack's son Steven was one of three occupants of a light plane killed when the aircraft crashed into the carport of an apartment building in Santa Monica, California, on November 26, 1993.

Pollack's daughter, Rebecca Pollack, served as vice president of film production at United Artists during the late 1990s.

He directed 12 different actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Jane Fonda, Gig Young, Susannah York, Barbra Streisand, Paul Newman, Melinda Dillon, Jessica Lange, Dustin Hoffman, Teri Garr, Meryl Streep, Klaus Maria Brandauer, and Holly Hunter. Young and Lange won Oscars for their performances in one of Pollack's movies.

President of the jury at the Cannes Film Festival in 1986

Member of the jury at the Cannes Film Festival in 1973

Lifelong friends with Robert Redford, both men have made their feature film acting debuts in War Hunt (1962).

It was the original choice to direct Dirty Harry (1971).

He was the first choice to direct The Saint (1997).

Owns and flies a Cessna Citation 750 jet, N138SP.

Battled cancer for almost nine months at the time of his death.

In 2000, I co-founder Anthony Minghella of "Mirage Enterprises" to produce films.

Kate Winslet dedicated her first Oscar win to Sydney Pollack and his partner in Mirage Enterprises, Anthony Minghella, following their deaths.

Pollack directed (and won an Oscar for) Out of Africa (1985), which is based on a book by Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen) that starts, "I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills". He also executive produced The No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency (2008), which is based on a series of books by Alexander McCall Smith, the first of which starts, "Mma Ramotswe had a detective agency in Africa, at the foot of the Kgale Hill". Smith's opening line is a deliberate literary reference to the opening line of Isak Dinesen's classic memoir about Kenya.

Filmed Aretha Franklin's acclaimed gospel album "Amazing Grace" live in 1972.

He supervised the English-language version of Visconti's "The Leopard", in which Burt Lancaster and the British actor Leslie French dubbed themselves. Many well-known American actors, including Howard Da Silva, Everett Sloane, and Thomas Gomez dubbed various European actors.

He was an accomplished jazz pianist.

Producer or executive producer for five Best Picture Oscar nominees: Tootsie (1982), Out of Africa (1985), Sense and Sensibility (1995), Michael Clayton (2007) and The Reader (2008), with Out of Africa winning Best Picture of 1985.

Born on the same date as Jean Marsh.

The film The Electric Horseman (1979) was his last scope (2.35 AR) film for a long period. Pollack switched to shooting full frame (soft matte) with a 1.85 intended AR. This was driven by the fear of what damage home video did to widescreen movies with pan-and-scan transfers. His last movie The Interpreter (2005) was shot in scope.

He has directed one film that has been selected for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically or aesthetically" significant: Tootsie (1982).

Alumnus of Stella Adler Studio of Acting.

Concerns about Pollack's health surfaced in 2007 when he withdrew from directing HBO's television film Recount, which aired on May 25, 2008.

Personal Quotes (29)

[on his favorite area of the filmmaking process] Editing, because I'm alone and there isn't the necessity of organizing so many people. Editing feels almost like sculpting or a form of continuing the writing process.

I don't value a film I've enjoyed making. If it's good, it's damned hard work.

[on working with Al Pacino on Bobby Deerfield (1977)] He's always asking questions. He's very hard on a director. In a nightclub scene, he asked, "Is this the first or second time we've been here?" He wants to know what day of the week it is for a scene. He wants to know the entire background to the relationship with the character played by Anny Duperey: "Did I pick her up? Did she pick me up?"

[on Paul Newman] There's stillness in his acting now that is quite magnetic. You can feel his intelligence, you can see him thinking. He has the depth of a clear pool of water.

[on Meryl Streep] The danger I'm talking about here is that she tends to sound boring because she's so perfect.

If we were a primitive society, movie stars would be gods.

I have been accused of playing [the romance] card too often, but I make no apologies because it engages people. How human beings connect, how they embrace and trust and love, engage people. And once you have that connection, the audience is paying attention, and all the rest works.

I'm from Indiana. If I get it, everyone gets it.

Look, two and two are four. Once you learn that, you know your way around numbers. The part of the business you can control is the business part. You have to be a fanatic about that. So you can be totally free to wander and be haphazard in the other area, where the creativity is. Anything is easier than art.

Tootsie (1982) tells the story of a really incredibly gifted actor played by Dustin Hoffman.

I try to work on the script while listening to certain things that make me feel at home with the world of the picture. I have thousands of songs on my laptop and iPod -- classical music, old standards, film scores by Morricone and Jerry Goldsmith, vocalists like Sinatra, Coldplay, and some newer rock bands, and pretty much everything but heavy metal.

John Frankenheimer always had a great sense of theatricality. And he was a real shooter. He had a wonderful sense of lenses and where to put the camera. Those were the early days of transitioning from live television into film, and John was always breaking cameras. We used these electric cameras that had tubes in them, and you couldn't put them cockeyed on the floor because they'd heat up and blow out. But John was always putting them in impossible positions because it was a big part of his style, those unorthodox setups. Of course, everybody that learned in those days was into wide angles and low angles. You put the camera on the floor and you used wide-angle lenses, and you shot up, and you put ceiling pieces in, and that was a big deal. Because in the old days of lighting, you had to leave the ceiling open for the lights-the film was slow, the lenses were slow.

Movies are like your kids or your fingers and toes or something, it's pretty hard to pick favorites. The truth of the matter is I like failures as much as I like successes; it's only the world that doesn't like failures. I don't have enough sense to distinguish between the two because I do the same thing when I make a failure as I do when I make a success. I really do. From my point of view, I work just as hard, I care just as much, if the films fail it doesn't make me suddenly disown them; it just doesn't. I would go back and make Havana (1990) again if it came to me, I would go back and make Random Hearts (1999); both pictures were failures. I mean, they were certainly failures financially. They were not at all failures in my mind. I mean, in Random Hearts (1999) I badly misjudged the audience's ability to accept Harrison Ford in a role other than what they really want to see him in. And looking back you can see that in everything. You can see it in Frantic (1988), and The Mosquito Coast (1986); these were all failures, not artistic failures, but they weren't as financially successful. When Harrison is in an action picture, he's so good, and that's what we want to see. We don't want to see him in pain, and in misery, and suffering.

[on making Sabrina (1995)] It wasn't a good idea by the way. I got clobbered for redoing Sabrina (1954). I thought I could add something because of the time that went by. But, it turned out that people really didn't want to see a remake of Sabrina (1954). But, I'm not a big fan of remakes.

Any creative act is an intimate act, and it's difficult to be intimate with strangers. The real creative part of movie-making is very revealing of yourself, the actors are very revealing of themselves, and you're making choices that expose yourself in a certain way. That's why it's so painful to be ripped apart in a review, because in a sense you feel you've undressed in front of the world and they're saying "oh, that's ugly".

I've had disagreements with everybody, but not screaming matches. I've only had that with one actor: Dustin [Dustin Hoffman] on Tootsie (1982). We had a lot of arguments about choices of behavior in scenes. Originally, the project belonged to him, and it was his vision. Then I took it over and, as much as I could, I made it into my vision. And those two visions weren't always in sync. We had a territory battle for a while, because we were transferring ownership. He has a slightly bawdier sense of humor than I do. He also wanted the movie to be more about the truths of actors' lives than I did. I don't say I'm right or he's right. I just saw it in a different way than he did, and we fought like hell. But we fought for the first half hour of the day, and when we started shooting, we didn't fight, and we did the scenes.

The wonderful thing about making movies, oddly enough, is that they're sort of highly motivated graduate studies in one or another field. If I make a film about 1850 in America, and mountain men, let's say I spend a year researching like crazy until I know exactly how you make a trap for a beaver, what a beaver pelt costs, how long could you go up into the mountains, what roots could you eat, what roots couldn't you eat, what was poison, what wasn't poison. I'm going to read every book there was, I read all the journals of Jim Bridger, and these guys who got mauled by grizzly bears, read all kinds of stuff about the Indians, and what the tribes were, and what the various characteristics were. So when I finish that picture, I've done a sort of graduate course in that field, in that area, that's highly motivated.

[on the editing process] That's really where the film gets made. I'm not good at editing while I'm shooting. They're two different processes to me, and I can't quite discipline my brain to do both of them at the same time. While I'm shooting, I'm searching for something. Then, in the editing, it becomes like sculpting. Editing is the process I enjoy the most. It's the one time when you're alone and you don't have to go through an army of 200 people to get what you want. On the set, I have to go through a cinematographer, a gaffer, a production designer and use the right lens, the right camera movement, the right lighting, the right clothes, and so many specific practical disciplines to translate my subconscious wishes. What you want to say to everyone is: "Can't you just reach into my brain and do what it is that I'm daydreaming?" When you're editing, you're in a dark room, you can try anything you want and it's instantaneous.

[on difference in shooting digitally rather than on film] It's all the difference in the world. The joke is that you don't need a cameraman anymore because you can fix everything later on. That's not really true at all, but what you can do digitally now is so astounding. Shooting on digital for me was essential in the documentary because it didn't have to do with how it looked, except for the architecture, which I wanted to do in very special light, so that I shot in Super 16 with cameramen and gaffers and all that. But the interviews had really to do with candor and truth and unselfconsciousness and the only way I could get that was to not show up with a crew. You can't ask a guy deeply personal questions about his process with 20 people standing there staring at him and a lot of lights. So the decision was to accept a lack of photographic quality in return for the truth. It was really shot on a home mini-DV camera. I liked the freedom of that. I liked that I didn't have to worry about shadows and spend hours [setting up]. I could just ask questions and if he got up and moved I could follow him.

Burt Lancaster was largely responsible for me becoming a director. And I'm going down to Union Settlement, to do a tribute for him, because a new book has just come out about him.

Television was the only training ground when I started. We were stuck in a Catch-22 then. Nobody would give you a job unless they saw your work, and nobody could see your work unless they gave you a job. It cost too much money and was too big a gamble to let someone direct a movie without any proof they could do it, so it was very hard to get that first break. Today you can shoot a whole movie with a fairly inexpensive digital camera and edit it on your home computer. And they can look pretty damn good.

Timing is a big thing with actors. You don't ever want to over-rehearse, but you don't want them under-prepared either. Part of the trick is knowing when to roll the cameras. So many times I'll see a performance peak during the rehearsal process and they never quite get it back. That's why I'd rather be rolling early.

I didn't believe that I'd ever be lucky enough to be able to make a living as an actor. And as a matter of fact, I never did until I gave up acting, that's the irony of life. But, I went away to New York, and I went to a very good acting school, by sheer luck, not because I was smart or knew about it. I studied with a man named Sanford Meisner, and I studied dance with Martha Graham, and all these people taught at this wonderful school called the Neighborhood Playhouse. It was extraordinary and I just sort of fell into it. And I came back after two years there, I was 19 years old when I finished, and I became Meissner's assistant, so I was like a coach. And I taught acting for years, and without knowing it that was the real thing that started bending me toward directing.

There's no question that a good script is an absolutely essential, maybe the essential thing for a movie. But, they say that it's a director's medium because all of the major decisions are made by the director, including who the writer is most of the time, or whether the writer will be rewritten. I mean, there isn't a single decision really, unless you're a beginning director and you have a very strong producer who is a creative producer, who's going to make those decisions, and that can happen, not often but it can. But, normally the director decides things like cast, where you'll shoot, when you'll shoot, is it going to be a long shot, is it going to be a close shot, is it going to go round and round the people, who's going to play the part, how fast are they going to talk, what's the pacing of the scene, what are they going to wear, where are you going to shoot it. All those decisions are directorial decisions, just as they are in the editing room.

Look at the influence it has, look at the economics it commands, look at the preoccupation in all cultures of the world, look at its power to spread ideas, look at it as a political tool, look at it as entertainment, no matter what point of view you look at it from it would be hard, other than the Internet, let's say, to find something that's changed and affected the world strongly. I mean, certainly it's the single biggest event, I think, in terms of popular entertainment, or art even, if you say that, of the 20th Century. It's been film. It's the 20th Century's real art form.

Essentially, when you do a play, you're reinterpreting a work of art that already exists. That's not what happens with a movie. With a movie you're creating from the beginning this particular work, let's not call it work of art, because very few movies are works of art, let's just call them bits of popular culture, whatever they are, sometimes very rarely by accident a movie becomes a work of art. You know, they don't start out that way. They may start out that way in the mind of the film makers, but from a studio point of view they're product.

Film is the one art form that combines all art forms. Every single art form is involved in film, in a way. I mean, certainly writing, painting, photography, dance, architecture, there is an aspect of almost every art form that is useful and that merges into film in some way. Film is a collective experience, as you know. Reading a novel of a private experience, very, very different, the nature of it is very different. The reader supplies all of the finishing touches in a novel. Exactly how the character looks is up to you. Exactly how the character sounds is up to you. Exactly the way they make love in a novel is really up to you, I don't care what's described. None of that is up to you in a film. Every little bit is given to you.

[accepting his Best Director Oscar for Out of Africa (1985)] I can't leave this podium without saying I could not have made this film without Meryl Streep - she is astounding personally, professionally, and always, and I can't thank her enough.

[2002 interview, asked if he considers Eyes Wide Shut (1999) to be a good film] I wouldn't know, to be honest with you. I saw the movie once; I saw it at a premiere. I was so nervous while I was watching it......I was so disturbed by my own performance that I didn't even go to the party - it was the LA premiere, and there was a big party afterward, I got up, and I went home. Now, maybe it was just the shock of seeing myself - I didn't know what to think of it, at first. I hear people that hate the movie, and I hear people that love the movie. I think that that's been the case with a lot of Stanley's movies. When A Clockwork Orange (1971) came out, I never heard such arguments; when The Shining (1980) came out, I never heard such arguments. When Full Metal Jacket (1987) came out, people were screaming and arguing in the streets. Ten years later, they're taught in film schools. There's never been a Stanley Kubrick movie that hasn't become in some way a classic. Will that happen with Eyes Wide Shut? Let's wait ten years - we'll see.

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson