Famous Italian Artist in the NYC Museum of Modern Art.

Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

August 2016

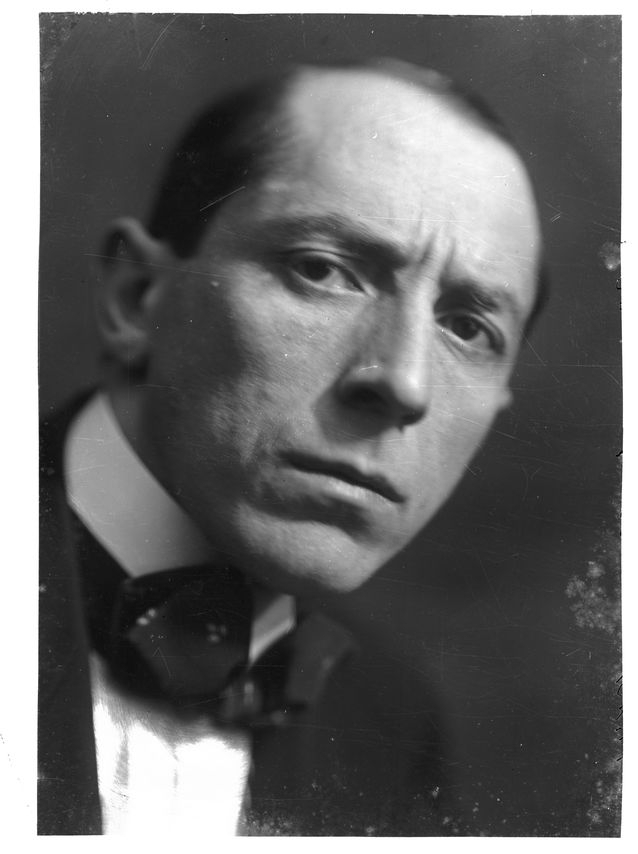

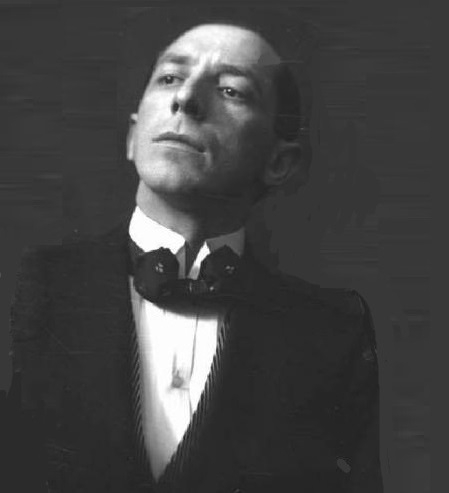

Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916) was the leading artist of Italian Futurism. During his short life, he produced some of the movement’s iconic paintings and sculptures, capturing the color and dynamism of modern life in a style he theorized and defended in manifestos, books, and articles.

Born in Reggio Calabria, Boccioni attended technical college in Catania, Sicily, and began his artistic career as a talented draftsman. He moved to Rome in 1899 to train as an artist, first taking drawing lessons with Giovanni Maria Mataloni, an artist who specialized in publicity posters. Boccioni’s skill in creating compelling compositions in cartoons and posters stayed with him throughout his career. The commercial work also provided a small income to support his training as a fine artist.

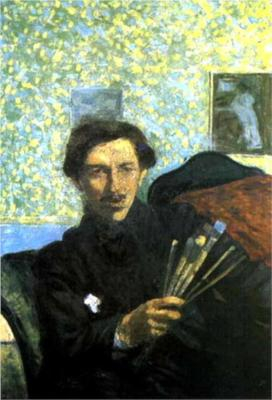

In 1902, he entered the studio of the established painter Giacomo Balla and met fellow student Gino Severini. As seen in Boccioni’s Young Man on a Riverbank (1902; 1990.38.6a), the two young artists would often leave the center of the ancient city to draw landscapes. Balla was known for Divisionism, an Italian style that shared the scientific basis of Pointillism, but with a more intuitive approach to applying strokes of color. Boccioni’s self-portrait (1990.38.4), painted in 1905 while still training with Balla, is in this style. This was the only painting by Boccioni accepted to the annual exhibition of the "Società degli Amatori e Cultori" in Rome that year. He showed others at the Salone di Rifutati, a venue for artists who had been rejected by the official salon.

Wanting to discover a city with a more established artistic avant-garde, Boccioni went to Paris in 1906; he found the city and its modern artists exhilarating. The following year, he moved to Venice (with stops in Russia, Warsaw, Vienna, and Padua), where he learned printmaking. His prints of this period depict friends, neighbors, and his mother (1990.38.34). They also hint at his burgeoning interest in the industrial city, which became a more constant subject after his move to Milan in August 1907 (1990.38.36).

In Milan, Boccioni met the poet F. T. Marinetti, the leader (and at that time the lone adherent) of the Futurist movement. In February 1909, Marinetti published his famous manifesto in the French newspaper Le Figaro, demanding that Italian culture stop looking backward and embrace modernity. In 1910, Boccioni, along with fellow Milanese painters Carlo Carrà and Luigi Russolo, wrote the “Manifesto of Futurist Painters,” which Balla and Severini also signed. This manifesto shared Marinetti’s enthusiasm for novelty and his distaste for artistic tradition, but failed to articulate what Futurist painting would look like, leading to the follow-up “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting.”

This manifesto called for the abandonment of traditional subjects like the nude. Instead, the Futurists would paint the modern life that surrounded them, following Marinetti’s declaration in “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism”: “We shall sing the great masses shaken with work, pleasure, or rebellion; we shall sing the multicolored and polyphonic tidal waves of revolution in the modern metropolis.”

Boccioni’s first major Futurist painting, The City Rises (1910; Museum of Modern Art, New York), embodies this declaration. The canvas is large-scale like a history painting, transforming the everyday labor of these anonymous workers into a monumental scene—the work’s original title was Lavoro (Labor or Work). Boccioni himself called it “a great synthesis of labor, light, and movement.” The rays of light that stream across parts of the canvas, the contorted poses of the people and animals, and the bright color palette all reinforce the painting’s dynamic sensation of movement. Yet Milan was the industrial hub of a still largely agricultural country, and so the picture, and its preparatory sketches (1990.38.16ab), focus not on a machine, but a horse.

Milan’s recently installed street lighting also offered Boccioni new urban subjects, as well as new light effects. He painted two scenes of unrest after dark, the more figurative and Divisionist Riot in the Gallery (1910; Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan), and the almost abstract and highly colorful Riot (1911; Museum of Modern Art, New York; 1990.38.19). The “Technical Manifesto” claimed: “The pallor of a woman eyeing a jeweler’s showcase is more iridescent than all the prisms of the jewels that fascinate her,” a notion that Boccioni gave form in his Modern Idol (1911; Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London; 1990.38.20).

In these early Futurist paintings, as in prior works such as his drawing for The Dream (1908–9; private collection; 1990.38.15), the influence of Symbolism and Expressionism—from Italian artists such as Giovanni Segantini and Gaetano Previati and international figures such as Edvard Munch—is still apparent. However, a shift in Boccioni’s style occurred in late 1911 when he encountered Cubist art on a trip to Paris. In a drawing of his lover Ines (1990.38.22b), Boccioni, for the first time, broke down the face into planes, in a similar way to Picasso’s depiction of his lover Fernande in 1909 (1996.403.6).

Boccioni’s interest in Cubism is most apparent in the two versions of the triptych States of Mind (first version: 1911, Museo del Novecento, Milan; second version: 1911, Museum of Modern Art, New York). As the title suggests, both sets of pictures relate to Boccioni’s goal of depicting mindsets, in this case, that of farewells, of those who go on a journey and those who stay behind. As apparent in the sketch for the first version of The Farewells (1911; 1990.38.22a) and the ink drawing after the second version of Those Who Go (1912; 1990.38.27), Boccioni integrates the Cubist use of collage-like numerals and straight lines that divide spatial planes into his more expressionistic style, like in Georges Braque’s Still Life with Banderillas (1911; 1999.363.11). Boccioni, however, deployed these motifs for Futurist ends: the dissected planes implied dynamism and the straight lines became “force lines” showing motion. In Elasticity (1912; Museo del Novecento, Milan), the image of the horse and rider is fractured, not to analyze and flatly present their volumes, but to capture and represent their dynamism, fuse them with the pylons, and bring the spectator into the center of the canvas.

Unlike the Cubists, Boccioni usually chose animate subjects. However, following the ideas of the French philosopher Henri Bergson, he believed that inanimate objects had inherent movement. Development of a Bottle in Space (1913; 1990.38.2) was the first publicly exhibited still-life sculpture, created less than a year after he wrote to his friend Vico Baer: “These days I am obsessed by sculpture! I believe I have glimpsed a complete renovation of that mummified art.” By using a static object, Boccioni could show the unfurling energy of the bottle, which seems to spiral out of its own original form.

His sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913; 1990.38.3) brings together the movement of the striding figure with that of the displaced air around that figure. Boccioni believed that “plastic dynamism” could only be achieved through a synthesis of relative motion (movement in relation to an environment) and absolute motion (dynamism inherent to an object). Unlike other Futurists, such as Balla, who sought to depict motion through repeating limbs, Boccioni wanted to create singular forms that expressed movement—Unique Forms is therefore considered the pinnacle of his sculptural activity.

Prior to these plaster sculptures (which were only cast posthumously), Boccioni had made three-dimensional works in mixed media, all of which are now destroyed. The plaster version of Antigraceful (1913; Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome; MMA bronze cast, 1950, 1990.38.1) survives without the metal protrusions—physical versions of “force-lines”—that emanated from the bust of the artist’s mother. Drawings for Boccioni’s even more extravagant mixed-media sculptures (1990.38.25; 1990.38.26) show how he merged figure and environment in a more literal way by intersecting an actual window frame into an early bust. Boccioni returned to mixed media in 1914–15 with Dynamism of a Speeding Horse + Houses (Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice).

After Boccioni published Futurist Painting and Sculpture theorizing his art in 1914, his style began to change. Rather than depicting dynamism, his interest in dissolving space with color, and in the work of Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne, increased. The workers in The Street Pavers (1914; 1990.38.5; see also 1990.38.28, 1990.38.29, and 1990.86) are not in action. Instead, the canvas itself, through the daubs of bright and pastel hues across its surface, becomes the site of movement, drawing the viewer’s eyes across the tangled forms of the composition.

Boccioni, like his fellow Futurists, was an ardent interventionist, campaigning for Italy’s entry into World War I on the side of the Allies. When Italy joined the war in 1915, he volunteered to fight. In August 1916, during cavalry exercises with his regiment, Boccioni fell from his horse. He died the next day at the age of thirty-three. Despite his premature death, he remains the best-known artist of the Futurist movement.

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson