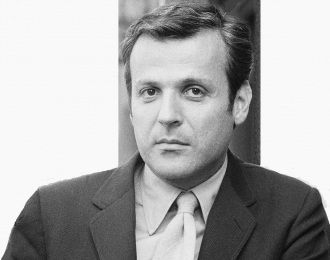

William Goldman

Born August 12, 1931, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

Died November 16, 2018 (aged 87), New York City, New York

Pen names: S. Morgenstern, Harry Longbaugh

Occupation

Non-fiction author novelist playwright screenwriter

Education Oberlin College (BA)

Columbia University (MA)

Genre Drama, fiction, literature, thriller

Spouse Ilene Jones (m. 1961; div. 1991)

Children 2

Relatives James Goldman (brother)

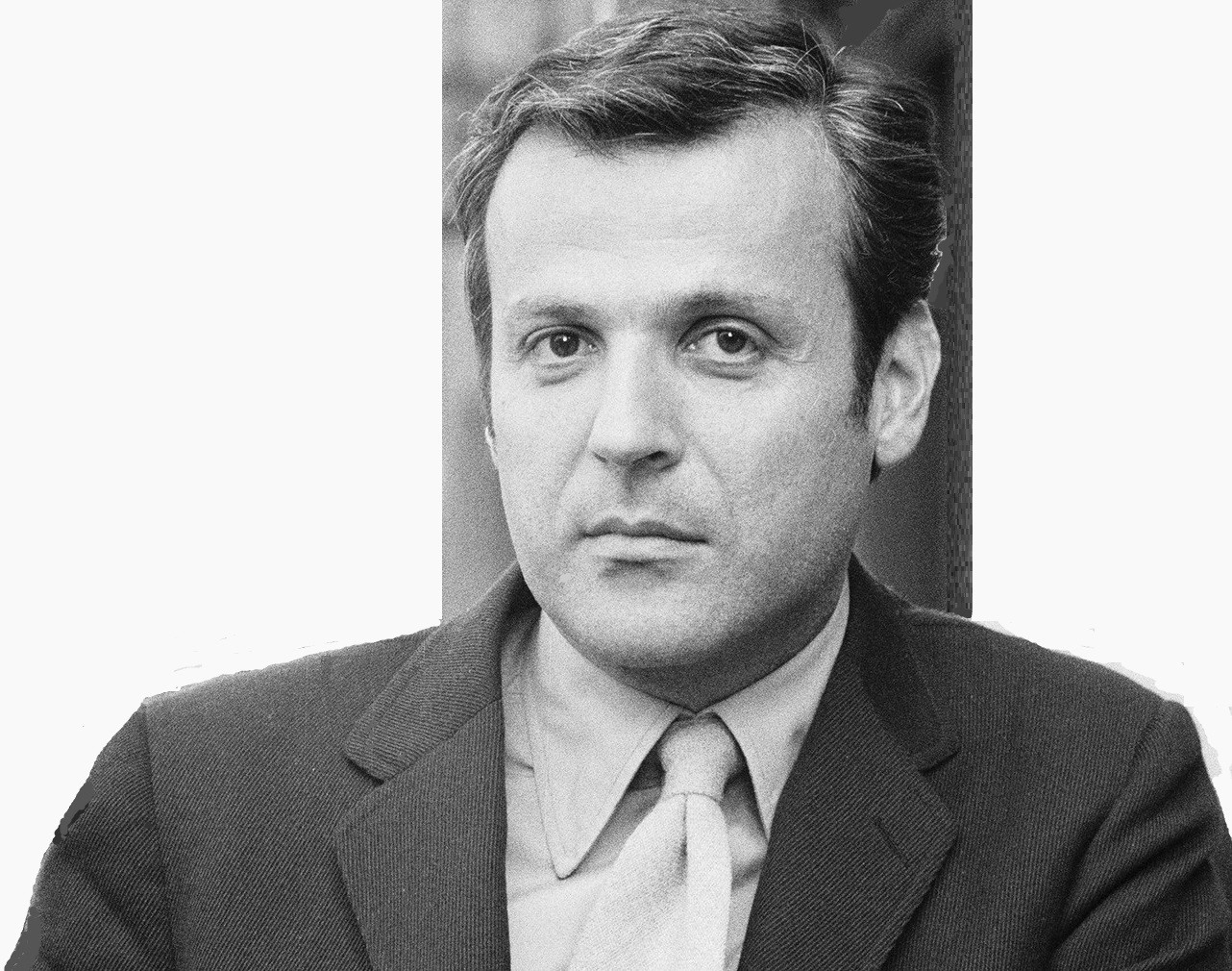

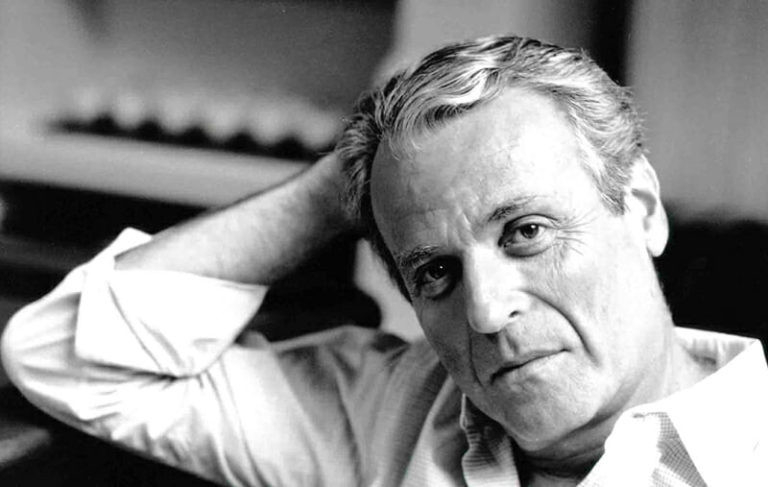

William Goldman (August 12, 1931 – November 16, 2018) was an American novelist, playwright, and screenwriter. He first came to prominence in the 1950s as a novelist before turning to screenwriting. Among other accolades, Goldman won two Academy Awards in both writing categories—once for Best Original Screenplay for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and once for Best Adapted Screenplay for All the President's Men (1976).

His other well-known works include his thriller novel Marathon Man (1974) and his cult classic comedy/fantasy novel The Princess Bride (1973), both of which he also adapted for film versions.

Early life

Goldman was born into a Jewish family in Chicago in 1931 and grew up in the Chicago suburb of Highland Park, Illinois, the second son of Marion (née Weil) and Maurice Clarence Goldman.

Goldman's father initially was a successful businessman, working in Chicago and in a partnership, but he suffered from alcoholism, which cost him his business.

He "came home to live and he was in his pajamas for the last five years of his life," according to Goldman.

His father died by suicide while Goldman was still in high school.

It was a 15-year-old Goldman who discovered the body.

His mother was deaf, which created additional stress in the home.

Education

Goldman received a Bachelor of Arts degree from Oberlin College in Ohio in 1952.

The Korean War was on, so he was drafted into the Army shortly thereafter.

Because he knew how to type, he was assigned as a clerk in the Pentagon, Defense headquarters. He was discharged with the rank of corporal in September 1954.

He returned to graduate studies under the GI Bill, earning a Master of Arts degree at Columbia University, graduating in 1956. Throughout this period, he was writing short stories in the evenings but struggled to have them published.

Novelist

According to his memoir Adventures in the Screen Trade (1983), Goldman began to write when he took a creative writing course in college. His grades in the class were "horrible". He was an editor of Oberlin's literary magazine. He submitted his short stories to the magazine anonymously; he recalls that the other editors read his submissions and remarked, "We can't possibly publish this s***." He did not originally intend to become a screenwriter. His main interests were poetry, short stories, and novels. In 1956, he completed a master's thesis at Columbia University on the comedy of manners in America.

His older brother James Goldman was a playwright and screenwriter. They shared an apartment in New York with their friend John Kander. Also, an alumnus of Oberlin, Kander was working on his Ph.D. in music, and the Goldman brothers wrote the libretto for his dissertation. Kander was the composer of more than a dozen musicals, including Cabaret and Chicago, and all three of them eventually won Academy Awards. On June 25, 1956, Goldman began writing his first novel The Temple of Gold, completing it in less than three weeks. He sent the manuscript to agent Joe McCrindle, who agreed to represent him; McCrindle submitted the novel to Knopf, who agreed to publish it if he doubled the length. It sold well enough in paperback to launch Goldman on his career. He wrote his second novel Your Turn to Curtsy, My Turn to Bow (1958) in a little more than a week. It was followed by Soldier in the Rain (1960), based on Goldman's time in the military. It sold well in paperback and was turned into a film, though Goldman had no involvement in the screenplay.

Theater work

Goldman and his brother received a grant to do some rewriting on the musical Tenderloin (1960). They then collaborated on their own play, Blood, Sweat and Stanley Poole (1961), and on the musical, A Family Affair (1962), written with John Kander. Both plays had short runs.

Goldman began writing Boys and Girls Together but found that he suffered writer's block. His writer's block continued, but he had an idea for the novel No Way to Treat a Lady (1964) based on the Boston Strangler. He wrote it in two weeks, and it was published under the pseudonym Harry Longbaugh—a variant spelling of the Sundance Kid's real name, which Goldman had been researching since the late 1950s. He then finished Boys and Girls Together, which became a best seller.

Screenwriter

Cliff Robertson read an early draft of No Way to Treat a Lady and hired Goldman to adapt the short story Flowers for Algernon for the movies.

Before he had even finished the script, Robertson recommended him to do some rewriting on the spy spoof Masquerade (1965), in which Robertson was starring. Goldman did that, then finished the Algernon script. Robertson disliked it, though, and hired Stirling Silliphant, instead, to work on what became Charly (1968).

Producer Elliot Kastner had optioned the film rights to Boys and Girls Together. Goldman suggested that Kastner make a film of the Lew Archer novels of Ross Macdonald and offered to do an adaptation. Kastner agreed, and Goldman chose The Moving Target. The result was Harper (1966) starring Paul Newman, which was a big hit.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

Goldman returned to novels, writing The Thing of It Is... (1967). He taught at Princeton and wished to write something, but he could not come up with an idea for a novel. Instead, he wrote Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, his first original screenplay, which he had been researching for eight years. He sold it for $400,000, the highest price ever paid for an original screenplay at that time. The movie was released in 1969, a critical and commercial success that earned Goldman an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. The money enabled Goldman to take some time off and research the nonfiction The Season: A Candid Look at Broadway (1969).

Goldman adapted Steven Linakis's novel In the Spring the War Ended into a screenplay, but it was not filmed. Neither were scripts of The Thing of It Is, which came close to being made several times in the early '70s, and Papillon, on which he worked for six months and three drafts; the book was filmed, but little of Goldman's work was used. He returned to novels with Father's Day (1971), a sequel to The Thing of It Is…. He also wrote the screenplay for The Hot Rock (1972).

The Princess Bride

Goldman's next novel was The Princess Bride (1973); he also wrote a screenplay, but it was more than a decade before the film was made. That same year, he contracted a rare strain of pneumonia, which resulted in his being hospitalized and affected his health for months. This inspired him to a burst of creativity, including several novels and screenplays.

Goldman's novel writing moved in a more commercial direction following the death of his editor Hiram Haydn in late 1973. This started with the children's book Wigger (1974), followed by the thriller Marathon Man (1974), which he sold to Delacorte as part of a three-book deal worth $2 million.

He sold movie rights to Marathon Man for $450,000.

His second book for Delacorte was the thriller Magic (1976), which he sold to Joe Levine for $1 million. He did the screenplays for the film versions of Marathon Man (1976) and Magic (1978).

He also wrote the screenplay for The Stepford Wives (1975), which he says was an unpleasant experience because director Bryan Forbes rewrote most of it; Goldman tried to take his name off it, but they would not let him.

He was reunited with director George Roy Hill and star Robert Redford on The Great Waldo Pepper (1975), which Goldman wrote from an idea of Hill.

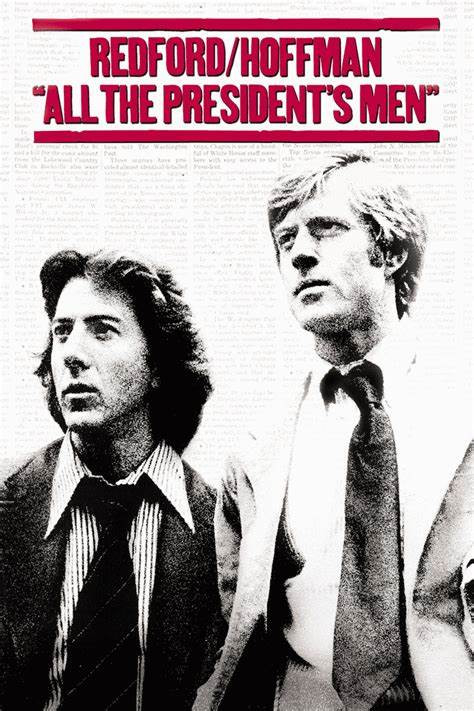

All the President's Men

Redford hired Goldman to write the script of All the President's Men (1976).

Goldman wrote the famous line "Follow the money" for the screenplay of All the President's Men; while the line is often attributed to Deep Throat, it is not found in Bob Woodward's notes nor in Woodward and Carl Bernstein's book or articles.

The book does have the far less quotable line from Woodward to Senator Sam Ervin, who was about to begin his own investigation: "The key was the secret campaign cash, and it should all be traced..."

Goldman was unhappy with the movie. The Guardian says that he changes the subject when asked about the movie, but suggests that his displeasure may be because he was pressured to add a romantic interest to the film. In his memoir, Goldman says of the film that if he could live his life over, he would have written the same screenplays, "Only I wouldn't have come near All the President's Men."

He said that he had never written as many versions of a screenplay as he did for that movie. Speaking of his choice to write the script, he said: "Many movies that get made are not long on art and are long on commerce. This was a project that seemed it might be both. You don't get many and you can't turn them down."

In Michael Feeney Callan's book Robert Redford: The Biography, Redford is reported as stating that Goldman did not actually write the screenplay for the movie, a story that was excerpted in Vanity Fair. Written By magazine conducted a thorough investigation of the screenplay's many drafts and concluded, "Goldman was the sole author of All The President's Men. Period."

Joseph E. Levine

Goldman was hired by Joseph E. Levine to write A Bridge Too Far (1977) based on the book by Cornelius Ryan. Goldman later wrote a promotional book, Story of A Bridge Too Far (1977), as a favor to Levine, and signed a three-film contract with the producer worth $1.5 million.

He wrote a novel about Hollywood, Tinsel (1979), which sold well. He wrote two more films for Levine, The Sea Kings and Year of the Comet, but did not write a third.

He did a script about Tom Horn; Mr. Horn (1979), was filmed for TV.

Goldman was the original screenwriter for the film version of Tom Wolfe's novel

The Right Stuff; Director Philip Kaufman wrote his own screenplay without using Goldman's material because Kaufman wanted to include Chuck Yeager as a character; Goldman did not.

He wrote a number of other screenplays around this time, including The Ski Bum; a musical adaptation of Grand Hotel (1932) that was going to be directed by Norman Jewison; and Rescue, the story of the rescue of Electronic Data Systems employees during the Iranian Revolution. None were made into films.

Adventures in the Screen Trade and the "Leper Period"

After several of his screenplays were not filmed, Goldman found himself in less demand as a screenwriter. He published a memoir about his professional life in Hollywood, Adventures in the Screen Trade (1983), which summed up the entertainment industry in the opening sentence of the book, "Nobody knows anything."

He focused on novels: Control (1982), The Silent Gondoliers (1983), The Color of Light (1984), Heat (1985), and Brothers (1986). The latter, a sequel to Marathon Man, was Goldman's last published novel.

Return to Hollywood

Goldman attributed his return to Hollywood to signing with talent agent Michael Ovitz at Creative Artists Agency. He went to work on Memoirs of an Invisible Man, although he left the project relatively early.

Hollywood's interest in Goldman was reawakened; he wrote the scripts for film versions of Heat (1986) and The Princess Bride (1987). The latter was directed by Rob Reiner for Castle Rock, which hired Goldman to write the screenplay for Rob Reiner's 1990 adaptation of Stephen King's novel Misery, considered "one of [King's] least adaptable novels". The movie, for which Kathy Bates received an Academy Award, performed well with critics and at the box office.

Goldman continued to write nonfiction regularly. He published a collection of sports writing, Wait Till Next Year (1988), and an account of his time as a judge at both the Cannes Film Festival and the Miss America Pageant, Hype and Glory (1990).

Goldman began to work steadily as a "script doctor", doing uncredited work on films including Twins (1988), A Few Good Men (1992), Indecent Proposal (1993), Last Action Hero (1993), Malice (1994), Dolores Claiborne (1995), and Extreme Measures. Most of these movies were by Castle Rock.

He was credited with several other movies: Year of the Comet (1992), which was eventually filmed by Castle Rock, but was not a success; the biopic Chaplin (1992), directed by Richard Attenborough; Maverick (1994), a popular hit; The Chamber (1996), from a novel by John Grisham; The Ghost and the Darkness (1996), an original script based on a true story; Absolute Power (1997) for Clint Eastwood; and The General's Daughter (1999), from the novel by Nelson DeMille.

Later career

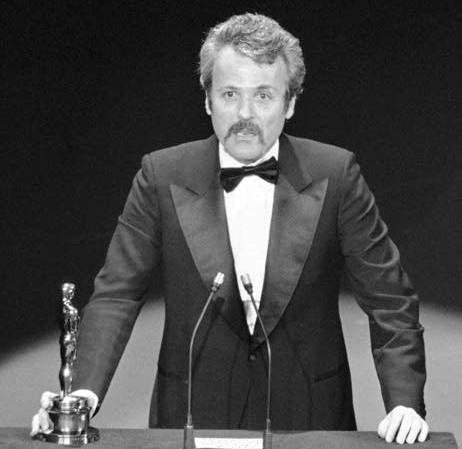

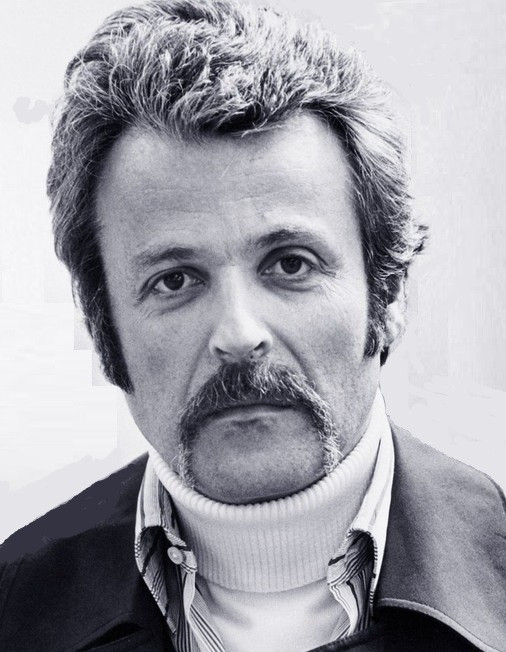

Goldman at the 2008 Screenwriting Expo

Goldman wrote another volume of memoirs, Which Lie Did I Tell? (2000), and a collection of his essays, The Big Picture: Who Killed Hollywood? and Other Essays (2001).

His later screenplay credits include Hearts in Atlantis (2001) and Dreamcatcher (2003), both from novels by Stephen King.

He adapted Misery into a stage play, which made its debut on Broadway in 2015 in a production starring Bruce Willis and Laurie Metcalf.

His script for Heat was filmed again as Wild Card (2015), starring Jason Statham.

After his death, screenwriter Peter Morgan wrote that Goldman had completed a final book on Hollywood, comparing the production of three different films, including Morgan's Frost/Nixon, but that the book had run into legal problems and was never published.

Critical reception

In their feature on Goldman, IGN said, "It's a testament to just how truly great William Goldman is at his best that I actually had to think hard about what to select as his 'Must-See' cinematic work". The site described his script for All the President's Men as a "model of storytelling clarity... and artful manipulation".

Art Kleiner, writing in 1987, said, "William Goldman, a very skilled storyteller, wrote several of the most well-known films of the past 18 years—including Marathon Man, part of All the President's Men, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid."

Three of Goldman's scripts have been voted into the Writers Guild of America hall-of-fame's 101 Greatest Screenplays list.

In his book evaluating Goldman's work, William Goldman: The Reluctant Storyteller (2014), Sean Egan said Goldman's achievements were made "without ever lunging for the lowest common denominator. Although his body of work has been consumed by millions, he has never let his populism overwhelm a glittering intelligence and penchant for upending expectation."

Self-appraisal

In 2000, Goldman said of his writing:

Someone pointed out to me that the most sympathetic characters in my books always died miserably. I didn't consciously know I was doing that. I didn't. I mean, I didn't wake up each morning and think, today I think I'll make a really terrific guy so I can kill him. It just worked out that way. I haven't written a novel in over a decade... and someone very wise suggested that I might have stopped writing novels because my rage was gone. It's possible. All this doesn't mean a hell of a lot, except probably there is a reason I was the guy who gave Babe over to Szell in the "Is it safe?" scene and that I was the guy who put Westley into The Machine. I think I have a way with pain. When I come to that kind of sequence I have a certain confidence that I can make it play. Because I come from such a dark corner.

Goldman also said of his work: "I don't like my writing. I wrote a movie called Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and I wrote a novel called The Princess Bride and those are the only two things I've ever written, not that I'm proud of, but that I can look at without humiliation."

Awards

He won two Academy Awards: one for Best Original Screenplay for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and Best Adapted Screenplay for All the President's Men.

He also won two Edgar Awards, from the Mystery Writers of America, for Best Motion Picture Screenplay: for Harper in 1967, and for Magic (adapted from his 1976 novel) in 1979. In 1985, he received the Laurel Award for Screenwriting Achievement from the Writers Guild of America.

Personal life

He was married to Ilene Jones from 1961 until their divorce in 1991; the couple had two daughters, Jenny and Susanna. Ilene, a native of Texas, modeled for Neiman Marcus; Ilene's brother was actor Allen Case.

Goldman said that his favorite writers were Miguel de Cervantes, Anton Chekhov, Somerset Maugham, Irwin Shaw, and Leo Tolstoy.

He was a die-hard fan of the New York Knicks, having held season tickets at Madison Square Garden for over 40 years. He contributed a writing section to Bill Simmons's bestselling book about the history of the NBA, in which he discussed the career of Dave DeBusschere.

Death

Goldman died at his Manhattan apartment on November 16, 2018, due to colon cancer complicated by pneumonia. He was 87.

Works

See also: Category: Works by William Goldman

Theatre

Produced

Tenderloin (1960), uncredited doctoring work

Blood, Sweat and Stanley Poole (1961), with James Goldman

A Family Affair (1962), lyrics; book was by James Goldman, music by John Kander

Misery (2012), adapted from the novel Misery

Unproduced

Madonna and Child – with James Goldman

Now I Am Six

Something Blue – musical

musical of Boys and Girls Together (aka Magic Town)

Nagurski – musical

The Man Who Owned Chicago – a musical with James Goldman and John Kander

musical of The Princess Bride – with Adam Guettel

(abandoned after royalty disputes)

Screenplays

Produced

Year Title Director Notes

1965 Masquerade Basil Dearden

1966 Harper Jack Smight

1969 Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid George Roy Hill Also producer (Uncredited);

Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay

BAFTA Award for Best Screenplay

Nominated- Golden Globe Award for Best Screenplay

1972 The Hot Rock Peter Yates

1975 The Stepford Wives Bryan Forbes

The Great Waldo Pepper George Roy Hill

1976 Marathon Man John Schlesinger Based on his novel;

Nominated- Golden Globe Award for Best Screenplay

All the President's Men Alan J. Pakula

Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay

Nominated- BAFTA Award for Best Screenplay

Nominated- Golden Globe Award for Best Screenplay

1977 A Bridge Too Far Richard Attenborough

1978 Magic Based on his novel

1986 Heat Dick Richards

Jerry Jameson

1987 The Princess Bride Rob Reiner

1990 Misery

1992 Memoirs of an Invisible Man John Carpenter

Year of the Comet Peter Yates

Chaplin Richard Attenborough

1994 Maverick Richard Donner

1996 The Chamber James Foley

The Ghost and the Darkness Stephen Hopkins

1997 Absolute Power Clint Eastwood

1999 The General's Daughter Simon West

2001 Hearts in Atlantis Scott Hicks

2003 Dreamcatcher Lawrence Kasdan

2015 Wild Card Simon West Based on his novel

Consultant

A Few Good Men (1992)

Malice (1993)

Dolores Claiborne (1995)

Extreme Measures (1996)

Good Will Hunting (1997)

Uncredited

Twins (1988)

Indecent Proposal (1993)

Last Action Hero (1993)

Fierce Creatures (1997)

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson