Countryman Family History & Genealogy

Countryman Last Name History & Origin

AddHistory

We don't have any information on the history of the Countryman name. Have information to share?

Name Origin

We don't have any information on the origins of the Countryman name. Have information to share?

Spellings & Pronunciations

We don't have any alternate spellings or pronunciation information on the Countryman name. Have information to share?

Nationality & Ethnicity

We don't have any information on the nationality / ethnicity of the Countryman name. Have information to share?

Famous People named Countryman

Are there famous people from the Countryman family? Share their story.

Early Countrymans

These are the earliest records we have of the Countryman family.

Countryman Family Members

Countryman Family Photos

Discover Countryman family photos shared by the community. These photos contain people and places related to the Countryman last name.

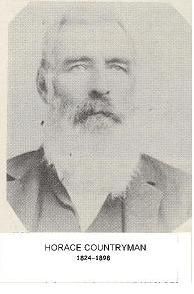

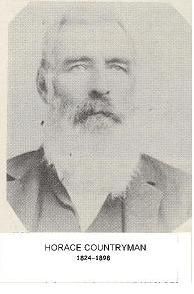

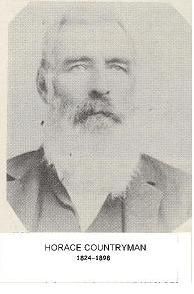

My father Horace Countryman put up the quartz mill at Summit, the first one in Montana, built the Masonic Hall in Virginia, (I have always had such a tender spot in my heart for Virginia). Also a mill at Highland Gulch, the Hope Mill at the Hope Mill at Philipsburg and the Masonic Hall there. Philipsburg

People in photo include: James Countryman

Countryman Family Tree

Discover the most common names, oldest records and life expectancy of people with the last name Countryman.

Updated Countryman Biographies

Popular Countryman Biographies

Countryman Death Records & Life Expectancy

The average age of a Countryman family member is 72.0 years old according to our database of 1,454 people with the last name Countryman that have a birth and death date listed.

Life Expectancy

Oldest Countrymans

These are the longest-lived members of the Countryman family on AncientFaces.

Other Countryman Records

Share memories about your Countryman family

Leave comments and ask questions related to the Countryman family.

Followers & Sources

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

By Jim Amin

Dear Jay: You will recall that about a year ago I suggested that I would write my findings of the part Horace Countryman played in getting the news of the Custer Massacre into the news media. My research began two years ago, where it occurred to me that in all the items I had read that name of Countryman was never mentioned. Because of personal acquaintance with some of the principals in this article I felt I could present an honest interpretation of the many dispatches that I have read covering this historical incident. I was eight years old when Mr. Countryman died, and had spoken to him many times, always in awe, because I looked upon him as a patriot and hero. From the time I was a schoolmate with the four granddaughters and eight grandsons enrolled at various times I often heard them proudly extol the heroics of "Granddad Horace".

Col. Wm. J. Norton, a one-time partner of Countryman in the stage coach stop at Stillwater, (now Columbus, Montana) was a correspondent for the Bozeman Times and Helena Herald in 1876, and is credited with news items as noted later. When he died in 1915 I assisted at his funeral, and later had access to his personal files, from which I got many items of historical value, among which was the press release printed in the San Diego Union.

This was the only copy he had of this dispatch, as carried by Countryman. In 1921 I sadly wrote the obituary of Mrs. Norton whom he had married in 1876, in which I mentioned that, as kids, we had traded her sage hens, ducks and fish for her wonderful Welsh tidbits. Another incident which involved the Countryman ride was in the spring of 1903 when Col. Norton addressed the three upper grades at the Columbus school, including the eighth grade graduates, giving most of the details of the dispatch when he had written for the Helena Record. Three students of the group of listeners are still alive but have forgotten most of the contents of this historical escapade.

In a historical and biographical edition of the History of Montana, published in 1885 appeared this notation in the Norton write-up "the first news of the Custer Massacre was sent by Mr. Norton to The Helena Herald." On June 25, 1876, the entire command of General Geo. Custer was annihilated by the combined tribes of Indians, mostly Sioux and Cheyenne, in a fierce, short-term battle on the Little Big Horn River in southeastern Montana. It was the greatest victory for the red men in the history of the Indian wars. Inasmuch as there were no survivors to tell about it, and only one Crow Indian, Curley, to see it, the details are minute. Various reports, assumed by speculation, are confusing and variable, and even to this day nobody actually, nor ever will, be certain as to the reasons and failure of the battle plan. Equally confusing were the reports of the Massacre as filed by the news media, and contradictory claims as to the source and timing of such releases. My purpose in compiling this article is two-fold: 1. To prove that the first news to reach the press was written by a news correspondent living in what is now my home town; and proudly boasting that I knew both of the men involved in compiling and delivering the account of the Custer Massacre.

2. To make people cognizant of the heroic service and character of "Muggins" Taylor, and the endurance and tragic message into the hands of startled readers all over the world. While not as important as the Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, nevertheless, it might well be written as an exciting event in American History. A correspondent of the Helena (Montana) Herald, writing from Stillwater, MT. June 22 said: Last evening John Williamson, the mail carrier from Gibbons Command, accompanied by three soldiers, arrived at this place with correspondent that he had just returned from Terry' column where he had been sent with dispatches by Gibbon, appraising that officer of the location of the Sioux camp. He met the command on Powder River.

This was also a Norton release, so the reporter was aware of the condition prior to the Massacre. In briefly reviewing the activities of both the Terry and Gibbon commands, one learns that they both took their time going from Fort Ellis to the mouth of the Big Horn, where Terry's cavalry was moved across the Yellowstone River on the Far West on the afternoon of June 25, and went into camp at Teluca Park. General Gibbons had camped at Stillwater for two nights during which he had gone to the newly established Crow Agency on Butcher Creek, where he recruited 25 Crow Scouts. Long after dark on the night of June 25, three of these scouts reported that they had been on the Custer Battlefield, and reported that there not a sign of any living --every soldier apparently had been killed, and many mutilated.

This was the first word of the tragedy to reach the Army officers. Aghast at this news General Terry awaited daylight, then moved his cavalry to a camp some three miles above the mouth of the Little Horn, after first appraising General Gibbon of his findings, and ordering the Far West to move to the mouth of the little Horn. The following is a capsule summary of my research: On the evening of June 27, 1876, General Terry's command was camped in the valley of the little Horn River, south of present Crow Agency, after by-passing the scene of the Custer Massacre. From this point Terry had heard sufficient evidence of the catastrophe to write an official report to the military headquarters of General Sheridan, in Chicago, which he gave to H.M. "Muggins" Taylor, under seal, for delivery to the post Commander, Capt. D.T. Benham, at Fort Ellis, the nearest station where government telegraph lines were available. The messenger knew the route southwestward to the Bridger-Bozeman trail, across the Big Horn river, but shortly after leaving the camp, he was apprehended by indians, and had to go north to the confluence with the Little Horn, where the steamer, Far West was to be at anchor. He had to take refuge overnight atop a rock formation with three cliff walls, and only a small path leading to the top. At break of daylight he sneaked down the trail, caught and mounted his horse, just as a group of Sioux-Cheyenne warriors again came in fast pursuit, firing rifles and releasing arrows. Luckily he was not hit by any of the missiles, and was only a few rods ahead of his enemies when he reached the Far West and safety. He was on the steamer until the wounded from Major Reno's command had been loaded, and at the mouth of the Big Horn river, in the early morning of July 1st he headed west up the Yellowstone on the Bismarck to Bozeman stage route, with 229 miles to Fort Ellis. In the late evening of July 2 he reached the stage station near Stillwater, completely exhausted by the little Horn experience and the fact that he had completed the first long step of his present mission.

Col. W.H. Norton, who was part-owner with Horace Countryman, was the official reporter for the Helena Herald. After hearing Taylor's story of the tragedy, Col. Norton summarized a message as Taylor had told it, and Countyman agreed to take the release to Bozeman for transmittal via wire to the Herald. He also, later on that evening, He wrote a similar report to be taken to the Bozeman times by Taylor, who rode on the next morning to Fort Ellis, where he delivered the sealed report. He then went on to Bozeman where he was interviewed by E. S. Willinson, editor of the Bozeman Times, and his account was released in a special edition of the Times at 7:00 P.M. July 3, the first report of the massacre to appear in print. When Countryman reached the telegraph office in Bozeman he found that the wires were down and service impossible. He immediately took on some food, got a fresh horse, and without rest resumed his 100 mile journey to Helena. When he reached the office of the Helena Herald, he too, was a near physical wreck, but he did give the Norton news to Andrew Fiske, a correspondent, who got enough printers together to get out a special edition of the Herald in the afternoon of July 4.

This same edition carried the Taylor dispatch from the Bozeman Times, both releases by Norton, and similar in content. That evening Manager Frederick of the Helena Associated Press sent the Countryman carried story to Salt Lake, where it was released in time for many eastern papers to get the news in their late editions on July 5. It was in general print all over the country on July 6. Also on July 4 The New Northwest of Deer Lodge carried the Bozeman Times release. The release from Helena apparently reached the General Headquarters in Chicago, because Congress got an unofficial report as they opened sessions July 6, and action on the situation was resolved. On July 2, aboard the Far West, General Terry wrote a confidential report to Generals Sheridan and Sherman. This dispatch was sent to Chicago (Fort Lincoln) entrusted to Capt. W. E. Smith, of Terry's staff, who was on the Far West. Capt. Marsh had the steamer on full blast and made the 710 miles at the high speed of thirteen miles per hour to Fort Abraham Lincoln at Bismarck, Dakota Territory, where Smith forwarded his report to General Sherman. The Bismarck Tribune put out a special edition at 11:30 A.M. July 6, over two days later than the Bozeman Times release, but, like the Taylor story, was not official. Smith's report was forwarded to General Sheridan, in Philadelphia at the time, but red tape prevented its official release and was not officially OKed by the War Department for release until July 9. The first Terry report, as carried by Muggins Taylor was in for trouble. When Captain T.D. Bonham, at Fort Ellis, had received it, he immediately went to the telegraph office and filed it. The next day, July 4, he went to check but the office was closed. On July 5 he was advised that the lines were down, so he had to send it by mail. On July 8 the letter reached Chicago and its contents officially released. This was the first official release by the Military. The following facts have been established: 1. The Bozeman Times was the first newspaper to print the news of the tragedy, which was done in a special edition at 7:00 P.M. July 3, 1876. This message was carried by Taylor. 2. In the early afternoon of July 4, The Helena Herald also came out with a special carrying the release dated at Stillwater on July 2. This release had been carried by Horace Countryman, The A. P. manager at Helena then forwarded the item to Salt Lake City, and from there was spread to the news media of America--the first to reach the nation. W.H. Norton prepared both the Countryman and Taylor releases, which were similar in content.

The Official Report from General Terry to the War Department: Headquarters Division of Dakota, Camp on Little Big Horn River, June 27 To Adjutant General of Military Division of Missouri, at Chicago, Illinois It is my painful duty to report that day before yesterday, the 25th instant., a great disaster overtook General Custer and the troops under his command. At 12 o'clock on the 22d he departed with his whole regiment and a strong detachment of scouts, and guards from the mouth of the Rosebud. Proceeding up that river about twenty miles, he struck a very heavy Indian trail, which had previously been discovered. Pursuing it, he found that it led, as it was supposed that it would, to the Little Big Horn River. There he found a village of almost unexampled extent, and at once attacked it with that portion of the forces which was immediately at hand. Major Reno, with three companies (A, G, and K of the regiment, was sent into the valley of the stream at a point where the trail struck it. General Custer, with five companies, (U, E, F, I and L) attempted to enter also three miles lower down. Reno forded the river and charged down the left bank, dismounted, and marched on foot, finally, overwhelmed by numbers, he was compelled to mount, recross the river, and seek shelter on the high bluffs which overlooked its right bank. Just as he recrossed, Captain Benton, who, with three companies (D, H, and K) who was some two miles on the left of Reno when the action commenced, but who had been ordered by General Custer to return came to the river and rightly concluding it was useless for his force to attempt to renew the fight in the valley, he joined Reno on the bluffs. Captain McDougal, with Company, was at first at some distance in the rear with a train of pack mules. He also came up to Reno. The united force was nearly surrounded by Indians, many of whom were armed with rifles, and occupied positions which commanded the ground held by the Cavalry, the ground from which there was no escape. Rifle pits were dug, and the fight maintained its position, though with heavy loss, from about half past two on the 26th till six o'clock on the 26th, when the Indians withdrew from the valley, taking with them their village. Of the movement of General Custer and the five companies under his immediate command, scarcely anything is known from those who witnessed them, for no officer or soldier who accompanied him has yet been found alive. Hs trail from the point where Reno crossed the stream, passes along and in the rear of the crest of the bluff on the right bank for nearly or quite three miles. It then comes down to the bank of the river, but at once diverged from it as though he had unsuccessfully attempted to cross. It then turns upon itself, almost completes a circle, and ceases. It is marked by the remains of his officers and men, and the bodies of his horses--some of them dropped along the path, others heaped where halts appear to have been made. There is abundant evidence that a gallant resistance was offered by the troops, but they were beset on all sides by overpowering numbers. (Unfortunately this message did not reach Chicago until July 8, 1876)

Extra Bozeman, Montana July 3d, 1876 7 P.M. Mr. Taylor, bearer of dispatches from the Little Horn to Fort Ellis, arrived this evening and reports the following: The battle was fought on the 25th, thirty or forty miles below the Little from. Custer attacked the Indian village of from 2,500 to 4,000 warriors, on one side, and Col. Reno was to attack it on the other. Three companies were placed on a hill as a reserve. General Custer and fifteen officers and every man belonging to the five companies were killed. Reno retreated under protection of the reserve. The whole number killed was 315. General Gibbon joined Reno. The Indians left. The battle ground looked like a slauter (sic) pen, as it really was, being in a narrow ravine. The dead were very much mutilated. The situation now looks serious. Gen. Terry arrived at Gibbon's camp on a steamboat and crossed the command over and accompanied it to join Custer, who knew it was coming before the fight occurred. Lieut. Crittendon, Son of Gen. Crittenden (spelling as given) was among the killed. The Indians surrounded Reno's command, and held them one day in the hills cut off from water, until Gibbon's command came in sight, when they broke camp in the night and left. The Seventh fought like tigers and were overcome by mere brute force. The Indian loss cannot be estimated as they bore off and cached the most of their killed. The remnant of the 7th Cavalry, and Gibbon's command are returning to mouth of the Little Horn where the steamboat lies. The Indians got all the arms of the killed soldiers. P. S. There were seventeen commissioned officers killed, and the whole Custer family died at the head of their column. The exact loss is not known, as both the Adjutant and Sergeant Major were killed. The Indian camp was from three to four miles long and was 20 miles up the Little Horn from its mouth. The Indians actually pulled men off their horses; in some instances. I give this as Taylor told me, as he was over the field after the battle. Respectfully, W. H. Norton

Helena Herald July 4 P.M. Helena, Mont., July 4--A special correspondent of the Herald writes from Stillwater, Montana, July 2, Muggins Taylor, a scout for General Gibbon, got here last night direct from Little Horn river. Gen. Custer found an Indian camp, consisting of about two thousand lodges, on the Little Horn, and immediately attacked the camp. Custer took five companies and charged the thickest portion of the camp. Nothing is known of the operations of this detachment, only as they trace it by the dead. Major Reno commanded the other seven companies, and attacked the lower portion of the camp. The Indians poured in a murderous fire from all directions; besides the greater portion fought on horseback. Custer, his two brothers, nephew and brother-in-law were all lolled, and not one of his detachment escaped. 207 men were buried in one place and the killed is estimated at 300, with only 81 wounded. The Indians surrounded Reno's command and held them one day in the hills cut off from water, until Gibbon's command and came in sight, when they broke camp in the night and left. The Seventh fought like tigers and were overcome by mere brute force. he Indian loss cannot be estimated, as they bore off and cashed most of their killed. The remnant of the Seventh Cavalry of Gibbons command are returning to the mouth of the Little Horn, where a steamboat lies. The Indians got all the arms of the killed soldiers. There were seventeen commissioned officers killed. The whole Custer family died at the head of their column. The exact loss is not known, as both adjutants and the sergeant-major were killed. The Indian camp was from three to four miles long, and was twenty miles up the Little Horn from its mouth. The Indians actually pulled men off their horses in some instances. I give this as Taylor told me, as he was over the field after the baffle. Respectfully submitted, Wm. H. Norton This was the message that was released to the news media, from the A.P. headquarters in Helena to Salt Lake City, and from there to the general news media.