October 25, 1972

OBITUARY

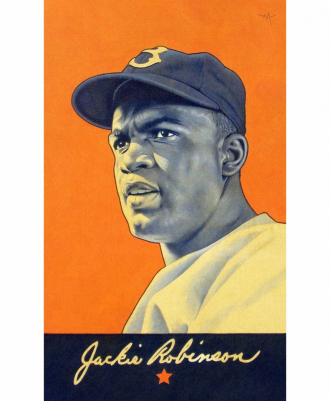

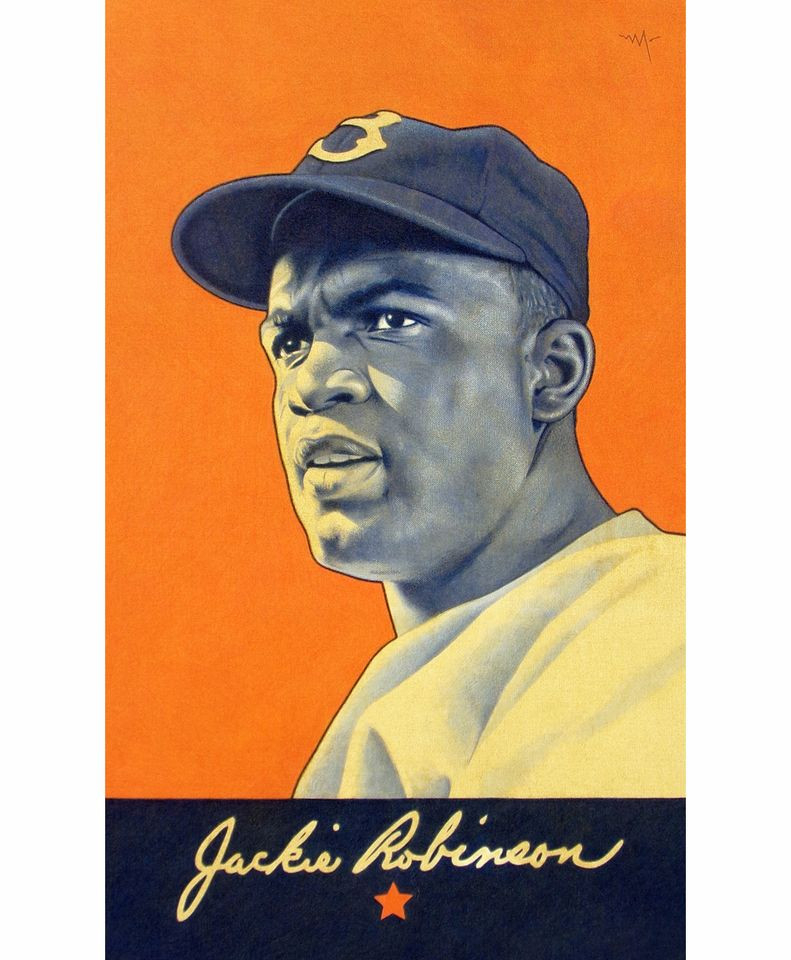

Jackie Robinson, First Black in Major Leagues, Dies

By DAVE ANDERSON

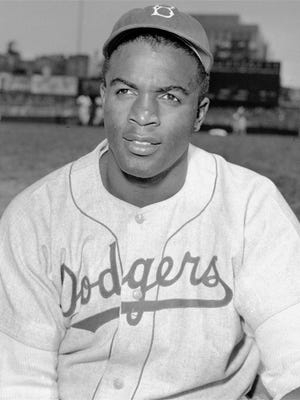

Jackie Robinson, who made history in 1947 by becoming the first black baseball player in the major leagues, suffered a heart attack in his home in Stamford, Conn., yesterday morning and died at Stamford Hospital at 7:10 A.M. He was 53 years old.

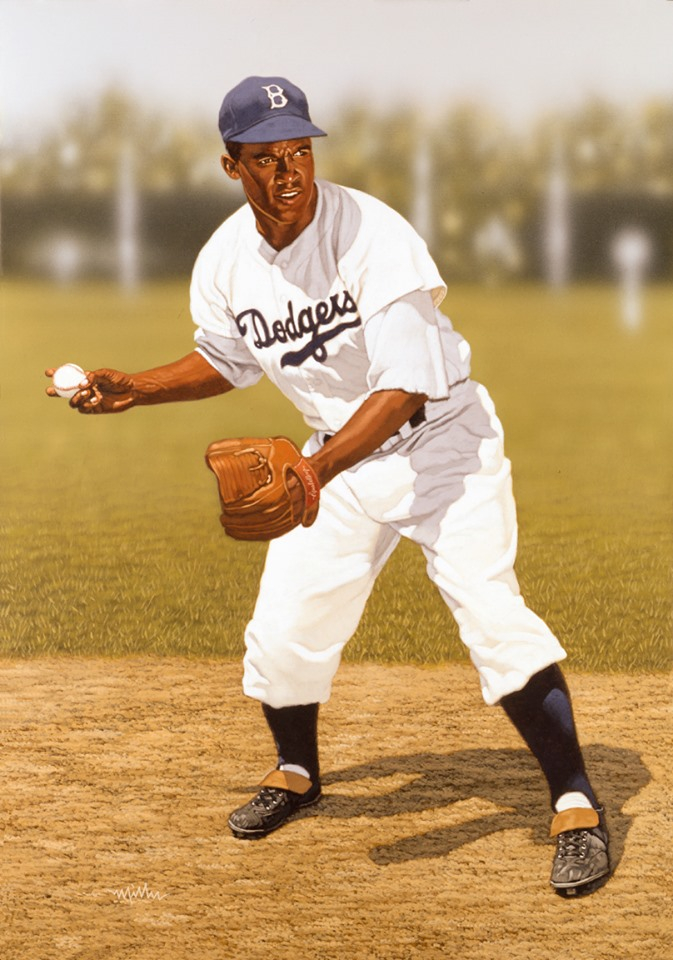

As an all-around athlete in college and later the star infielder of the Brooklyn Dodgers, he became the pioneer for a generation of blacks in major professional sports after World War II.

Mr. Robinson, who was honored at the World Series in Cincinnati a week ago Sunday, had been in failing health for several years. He recovered from a heart attack in 1968 but then lost sight of one eye and partial sight of the other due to diabetes.

He remained active, though, in national campaigns against drug addiction--from which his son, Jackie Jr., had been recovering before he was killed in 1971 in an automobile accident. In fact, Mr. Robinson planned to attend a drug symposium yesterday sponsored by the business community in Washington.

When he was stricken at home, an emergency call was made to the Stamford police by his wife, Rachel, who is an associate professor of psychiatric nursing at the Yale School of Medicine. They applied external massage and oxygen before a Fire Department ambulance took him to the hospital.

For sociological impact, Jack Roosevelt Robinson was perhaps America's most significant athlete.

As the first black player in major-league baseball, he was a pioneer. His skill and accomplishments resulted in the acceptance of blacks in other major sports, notably professional football and professional basketball. In later years, while a prosperous New York businessman, he emerged as an influential member of the Republican party.

His dominant characteristic, as an athlete and as a black man, was a competitive flame. Outspoken, controversial, and combative, he created critics and loyalists. But he never deviated from his opinions.

Commented on Debut

In his autobiography, "I Never Had It Made," to be published next month by G. P. Putnam, he recalled the scene in 1947 when he stood for the National Anthem at his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

He wrote:

". . .but as I write these words now I cannot stand and sing the National Anthem. I have learned that I remain a black in a white world."

Describing his struggle, he wrote:

"I had to fight hard against loneliness, abuse, and the knowledge that any mistake I made would be magnified because I was the only black man out there. Many people resented my impatience and honesty, but I never cared about acceptance as much as I cared about respect."

His belligerence flared throughout his career in baseball, business, and politics.

"I was told that it would cost me some awards," he said last year. "But if I had to keep quiet to get an award, it wasn't worth it. Awards are great, but if I got one for being a nice kid, what good is it?"

To other black ballplayers, though, he was most often saluted as the first to run the gantlet. Monte Irvin, who played for the New York Giants while Robinson was with the Dodgers and who now is an assistant to the commissioner of baseball, said yesterday:

"Jackie Robinson opened the door of baseball to all men. He was the first to get the opportunity, but if he had not done such a great job, the path would have been so much more difficult.

"Bill Russell says if it hadn't been for Jackie, he might never have become a professional basketball player. Jack was the trailblazer, and we are all deeply grateful. We say, thank you, Jackie; it was a job well done."

"He meant everything to a black ballplayer," said Elston Howard, the first black member of the New York Yankees, who is now on the coaching staff. "I don't think the young players would go through what he did. He did it for all of us, for Willie Mays, Henry Aaron, Maury Wills, and myself.

"Jack said he hoped someday to see a black manager in baseball. Now I hope some of the owners will see how important that would be as the next step."

Elected to the Hall of Fame

After a versatile career as a clutch hitter and daring base runner, while playing first base, second base, third base, and left field at various stages of his 10 seasons with the Brooklyn Dodgers, he was elected to baseball's Hall of Fame in 1962, his first year of eligibility for the Cooperstown, N.Y., shrine.

Despite his success, he minimized himself as an "instrument, a tool." He credited Branch Rickey, the Brooklyn Dodger owner who broke professional baseball's color line. Mr. Rickey signed him for the 1946 season, which he spent with the Dodger's leading farm, the Montreal Royals of the International League.

"I think the Rickey Experiment, as I call it, the original idea, would not have come about as successfully with anybody other than Mr. Rickey," he often said. "The most important results of it are that it produced understanding among whites and it gave black people the idea that if I could do it, they could do it, too, that blackness wasn't subservient to anything."

Among his disappointments was the fact that he never was allowed to be a major-league manager.

"I had no future with the Dodgers because I was too closely identified with Branch Rickey, "he once said. "After Walter O'Malley took over the club, you couldn't even mention Mr. Rickey's name in front of him. I considered Mr. Rickey the greatest human being I had ever known."

Robinson kept baseball in perspective. Ebbets Field, the Brooklyn ballpark that was the stage for his drama, was leveled shortly after Mr. O'Malley moved the Dodger franchise to Los Angeles in 1958.

Apartment houses replaced it. Years later, asked what he felt about Ebbets Field, he replied:

"I don't feel anything. They need those apartments more than they need a monument to the memory of baseball. I've had my thrills."

He also had heartbreak. His older son, Jackie Jr., died in 1971 at the age of 24 in an automobile accident on the Merritt Parkway, not far from the family's home in Stamford.

Son Became Drug Addict

Three years earlier, Jackie Jr. had been arrested for heroin possession. His addiction had begun while he served in the Army in Vietnam, where he was wounded. He was convicted and ordered to undergo treatment at the Daytop drug abuse center in Seymour, Conn. Cured, he worked at Daytop, helping other addicts, until his fatal accident.

Robinson and his wife, Rachel, had two other children--David and Sharon.

"You don't know what it's like," Robinson said at the time, "to lose a son, find him, and lose him again.

My problem was my inability to spend much time at home. I thought my family was secure, so I ran everywhere else. I guess I had more of an effect on other people's kids than I did my own."

With the Dodgers, he had other problems. His arrival in 1947 prompted racial insults from some opponents, an aborted strike by the St. Louis Cardinals, an alleged deliberate spiking by Enos Slaughter of the Cardinals, and stiffness from a few teammates, notable Fred (Dixie)Walker, a popular star from Georgia.

"Dixie was very difficult at the start," Robinson acknowledged, "but he was the first guy on the ballclub to come to me with advice and help for my hitting. I knew why--if I helped the ballclub, it put money in his pocket. I knew he didn't like me anymore in those few short months, but he did come forward."

A Cautioning by Rickey

As a rookie, Robinson had been warned by Mr. Rickey of the insults that would occur.

He also was urged by Mr. Rickey to hold his temper. He complied.

But the following season, as an established player, he began to argue with the umpires and duel verbally with opponents in the traditional give-and-take of baseball.

As the years passed, Robinson developed a close relationship with many teammates.

"After the game, we went our separate ways," he explained. "But on the field, there was that understanding.

No one can convince me that what happened at the ball club didn't affect people.

The Dodgers were something special, but of my teammates, there was nobody like Pee Wee Reese for me."

In Boston once, some Braves' players were taunting Robinson during infield practice. Reese, the popular shortstop, who came from Louisville, moved to the rescue.

"Pee Wee walked over and put his arm on my shoulder, as if to say, "This is my teammate, whether you like it or not,'" Robinson said. "Another time, all our white players got letters, saying if they don't do something, the whole team will be black and they'll lose their jobs. On the bus to the ballpark that night, Pee Wee brought it up, and we discussed it. Pretty soon, we were all laughing about it."

In clubhouse debates, Robinson's voice had a sharp, angry tone that rose with his emotional involvement.

"Robinson," he once was told by Don Newcombe, a star pitcher, who was also black, "not only are you wrong, you're loud wrong."

As a competitor, Robinson was the Dodgers' leader. In his 10 seasons, they won six National League pennants--1947, 1949, 1952, 1953, 1955, and 1956. They lost another in the 1951 playoff with the New York Giants, and another to the Philadelphia Phillies on the last day of the 1950 season.

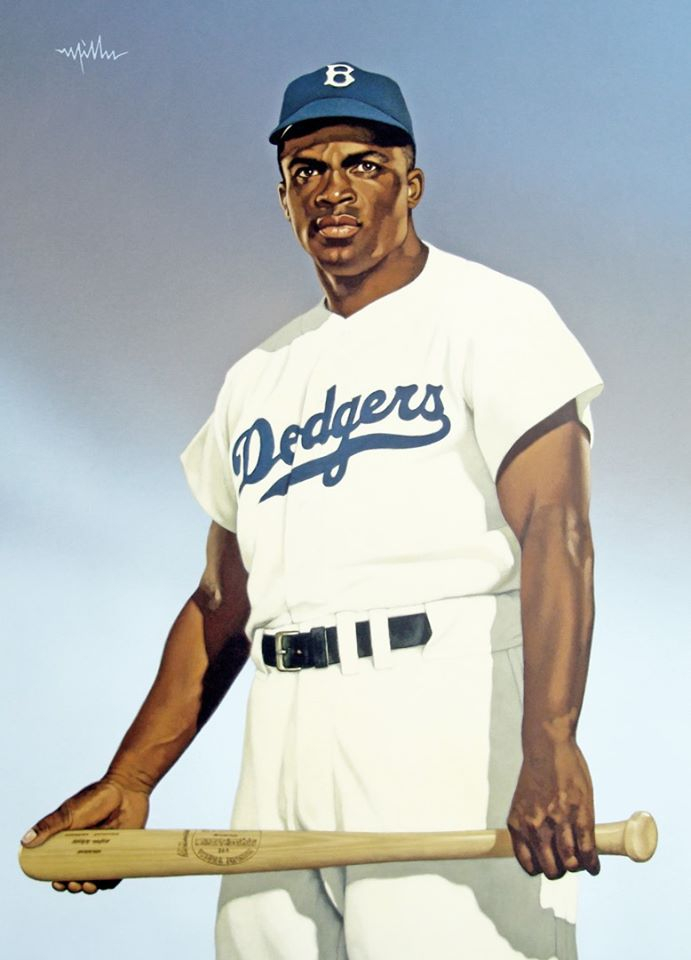

In 1949, when he batted .342 to win the league title and drove in 124 runs, he was voted the league's Most Valuable Player Award. In 1947, he was voted the Rookie of the Year.

Batted .311 Lifetime

"The only way to beat the Dodgers," said Warren Giles, then the president of the Cincinnati Reds, later the National League president, "is to keep Robinson off the bases."

He had a career batting average of .311. Primarily a line-drive hitter, he accumulated only 137 home runs, with a high of 19 in both 1951 and 1952.

But on a team with such famous sluggers as Duke Snider, Gil Hodges, and Roy Campanella, who was also black, he was the cleanup hitter, fourth in the batting order, a tribute to his ability to move along teammates on base.

But his personality flared best as a baserunner. He had a total of 197 stolen bases. He stole home 11 times, the most by any player in the post-World War II era.

Ran Like a Football Player

"I think the most symbolic part of Jackie Robinson, ball player," he once reflected, "was making the pitcher believe he was going to the next base. I think he enjoyed that the most, too. I think my value to the Dodgers was disruption--making the pitcher concentrate on me instead of on my teammate who was at bat at the time."

In the 1955 World Series, he stole home against the New York Yankees in the opening game of Brooklyn's only World Series triumph.

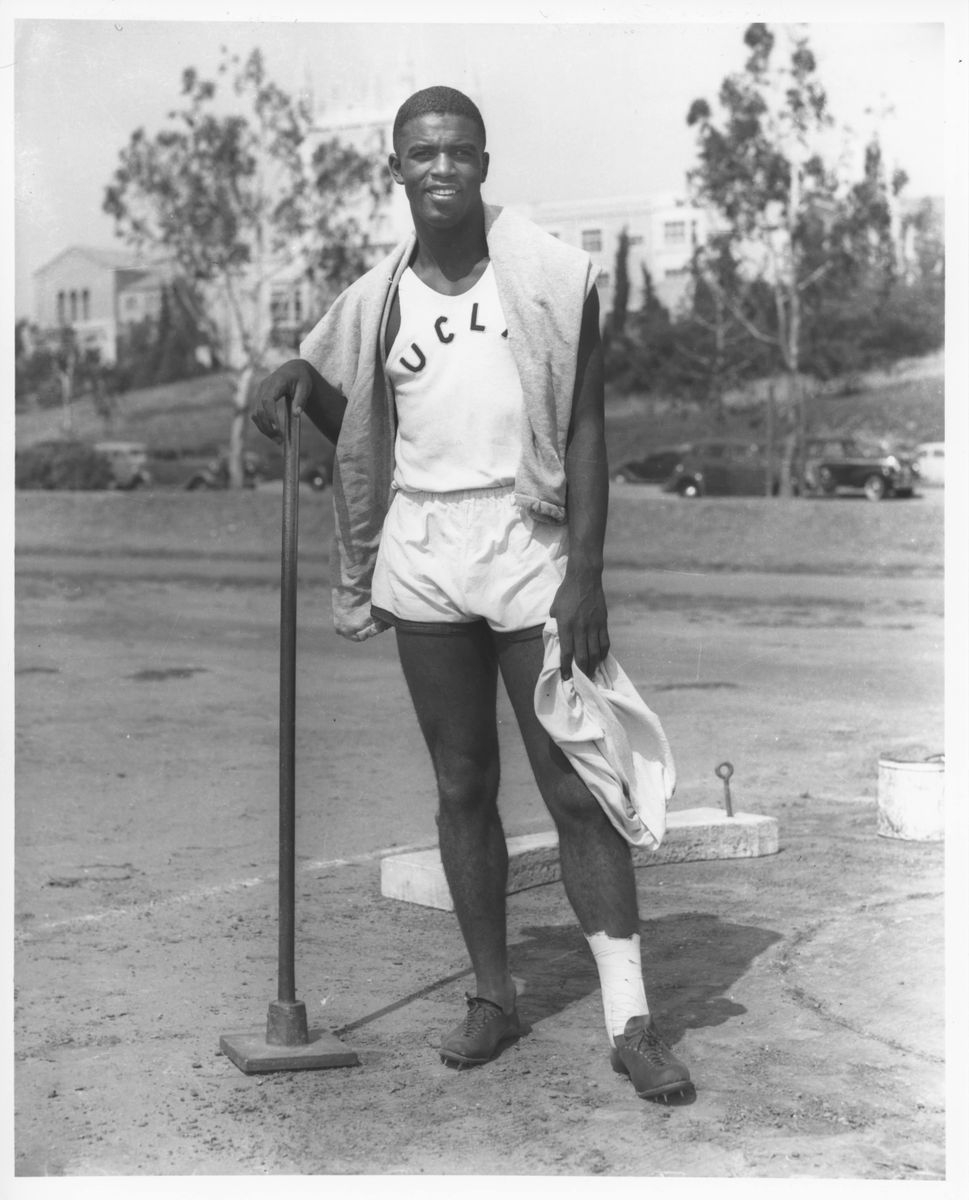

Pigeon-toed and muscular, wearing No. 42, he ran aggressively, typical of his college football training as a star runner and passer at the University of California at Los Angeles in 1939 and 1940. He ranked second in the Pacific Coast Conference in total offense in 1940 with 875 yards- -440 rushing and 435 passing.

Born in Cairo, Ga., on Jan. 31, 1919, he was soon taken to Pasadena, Calif., by his mother with her four other children after his father had deserted them. He developed into an all-around athlete, competing in basketball and track in addition to baseball and football. After attending U.C.L.A., he entered the Army.

He was commissioned a second lieutenant. After his discharge, he joined the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro National League as a shortstop.

"But if Mr. Rickey hadn't signed me, I wouldn't have played another year in the black league," he said. "It was too difficult. The travel was brutal. Financially, there was no reward. It took everything you made to live off."

If he had quit the Black leagues without having been signed by Mr. Rickey, what would he have done?

"I more than likely would have gone to coach baseball at Sam Houston College. My minister had gone down there to Texas as president of the college. That was about the only thing a black athlete had left then, a chance to coach somewhere at a small black college."

Instead, his presence turned the Dodgers into the favorite of black people nationwide.

"They picked up 20 million fans instantly," said Bill Russell, the famous center of the Boston Celtics who was professional basketball's first black coach. "But to most black people, Jackie was a man, not a ballplayer. He did more for baseball than baseball did for him. He was someone that young black athletes could look up to."

As the Dodgers toured the National League, they set attendance records. But the essence of Robinson's competitive fury occurred in a 1954 game at Ebbets Field with the rival Giants.

Sal Maglie, the Giants' ace who was known as "The Barber" because of his tendency to "shave" a batter's head with his fastball and sharp-breaking curve, was intimidating the Dodger hitters. In the Dodger dugout, Reese, the team captain, spoke to the 6-foot, 195-pound Robinson.

"Jack," said Reese, "we got to do something about this."

Robinson soon was kneeling in the on-deck circle as the next Dodger batter. With him was Charlie DiGiovanna, the team's adult batboy who was a confidant of the players.

"Let somebody else do it, Jack," DiGiovanna implored. "Every time something comes up, they call on you."

Robinson agreed, but once in the batter's box, he changed his mind. Hoping to draw Maglie toward the first-base line, Robinson bunted. The ball was fielded by Whitey Lockman, the first baseman, but Maglie didn't move off the ground. Davey Williams, the second baseman, covered the base for Lockman's throw.

Knocked Over Williams

"Maglie wouldn't cover," Robinson recalled. "Williams got in the way. He had a chance to get out of the way, but he just stood there right on the base. It was just too bad, but I knocked him over. He had a Giant uniform on.

That's what happens."

In the collision, Williams suffered a spinal injury that virtually ended his career. Two innings later, Alvin Dark, the Giants' captain, and shortstop retaliated by trying to stretch a double into a third-base collision with Robinson.

Realizing that Dark hoped to avenge the Williams incident, Robinson stepped aside and tagged him in the face. But his grip on the ball wasn't secure. The ball bounced away. Dark was safe.

"I would've torn his face up." Robinson once recalled. "But as it turned out, I'm glad it didn't happen that way. I admired Al for what he did after I had run down Williams. I've always admired Al, despite his racial stands. I think he really believed that white people were put on this earth to care for black people."

Ironically, after the 1956 season, Robinson was traded to the rival Giants, but he announced his retirement in Look magazine. Any chance of his changing his mind ended when Emil (Buzzy) Bavasi, then a Dodger vice president, implied that after Robinson had been paid for the by-line article, he would accept the Giants' offer.

A succession of Executive Posts

"After Buzzy said that," Robinson later acknowledged, "there was no way I'd ever play again."

He joined Chock Full O'Nuts, the lunch-counter chain, as an executive. He later had a succession of executive posts with an insurance firm, a food-franchising rim, and an interracial construction firm. He also was chairman of the board of the Freedom National Bank in Harlem and a member of the New York State Athletic Commission.

In politics, Mr. Robinson remained outspoken. He supported Richard M. Nixon in the 1960 Presidential election. When Mr. Nixon and Spiro T. Agnew formed the 1968 Presidential ticket, however, he resigned from Governor Rockefeller's staff, where he was a Special Assistant for Community Affairs, to campaign for Hubert H. Humphrey, the Democratic nominee.

Mr. Robinson described Mr. Nixon's stand on civil rights in 1960 as "forthright" but denounced the Nixon-Agnew ticket as "racist."

Mr. Robinson's niche in American history is secure--his struggle predated the emergence of "the first black who" in many areas of American society. Even though he understandably needed a Branch Rickey to open the door for him, Branch Rickey needed a Jackie Robinson to lead other blacks through that door.

In addition to his wife, a fellow student at U.C.L.A. whom he married in 1946, Mr. Robinson leaves a son, David; a daughter, Mrs. Sharon Mitchell of Washington; a sister, Mrs. Willie Mae Walker, and two brothers, Mack and Edgar, all of Pasadena, Calif.

A funeral service will be held Friday at noon at the Riverside Church, Riverside Drive, and 122d Street. Visiting hours will be from noon to 9 P.M. at the church tomorrow.

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson