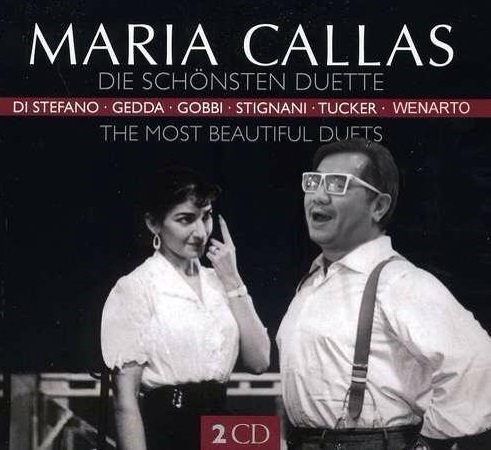

Maria Callas

Date & Place:

Not specified or unknown.

Uncover new discoveries and connections today by sharing about people & moments from yesterday.- Discover how AncientFaces works.

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Family, friend, or fan...

share memories, stories,

photos, or simply leave

a comment to show

you care.

Remember the past to connect today & preserve for tomorrow.

|

Partner

Sibling

Child

|

Connect with others who remember Maria Callas to share and discover more memories. People who have contributed to this page are listed below and in the Biography History of changes. Sign in to your free account to view changes.