Buck Family History & Genealogy

Buck Last Name History & Origin

AddHistory

We don't have any information on the history of the Buck name. Have information to share?

Name Origin

We don't have any information on the origins of the Buck name. Have information to share?

Spellings & Pronunciations

We don't have any alternate spellings or pronunciation information on the Buck name. Have information to share?

Nationality & Ethnicity

We don't have any information on the nationality / ethnicity of the Buck name. Have information to share?

Famous People named Buck

Are there famous people from the Buck family? Share their story.

Early Bucks

These are the earliest records we have of the Buck family.

Buck Family Members

Buck Family Photos

Discover Buck family photos shared by the community. These photos contain people and places related to the Buck last name.

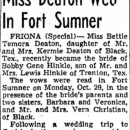

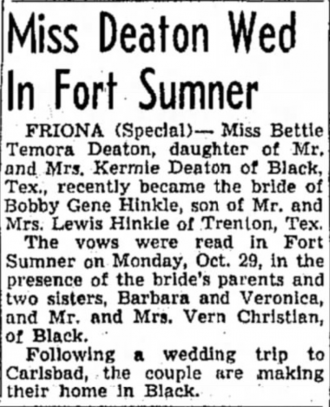

The vows were read in Fort Sumner on Monday, Oct. 29, in the presence of the bride's parents and two sisters, Barbara and Veronica, and Mr. and Mrs. Vern Christian, of Black.

Following a wedding trip to Carlsbad, the couple are making their home in Black.

Clovis News-Journal (Clovis, New Mexico) Sun, Nov 11, 1951 ·Page 12

Her parents were Southern Presbyterian missionaries who had previously live in China and they returned with her when she was 3 months old. She grew up there and lived in China, on and off, for many years as an adult.

She was a prolific author and a teacher.

People in photo include: William Amos Buck

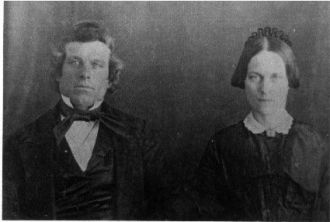

People in photo include: Horace R. Buck and Mary (Easton) Buck

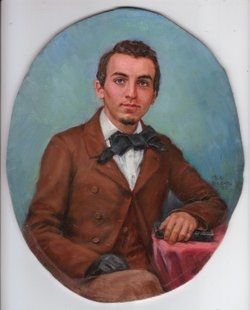

People in photo include: Charles Lunsford Neville Buck

Buck Family Tree

Discover the most common names, oldest records and life expectancy of people with the last name Buck.

Updated Buck Biographies

Popular Buck Biographies

Buck Death Records & Life Expectancy

The average age of a Buck family member is 74.0 years old according to our database of 16,812 people with the last name Buck that have a birth and death date listed.

Life Expectancy

Oldest Bucks

These are the longest-lived members of the Buck family on AncientFaces.

Other Buck Records

Share memories about your Buck family

Leave comments and ask questions related to the Buck family.

Shawnee Twp. T9S R10E

Located in Shawnee Twp. 2 miles North of Old Shawneetown on the Round Pound Road, on a high hill. The Cemetery is deserted and very much overgrown. Located in Sec. 17., T9S R10E. the land for this cemetery was entered by Warner Buck in 1815. It is one of the oldest cemeteries in the County.

Buck, Warner D. 1825 wife Barbara(Slusher, Schlosser) died prior to 1825.(Cannot locate marble slab about 4x6 feet which was for this couple. Stone was still in cemetery in the 1940's. Warner Buck was a Hessian Soldier in the Revolution and Deserted to American Forces. Married in Frederick Co. Va. on March 26,1782. He was one of the very early settlers in Gallatin Co.

Followers & Sources