Advertisement

Advertisement

Debby Stevens

About me:

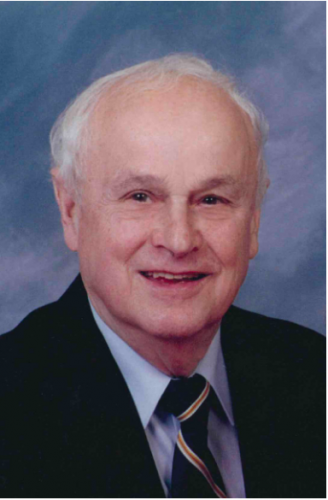

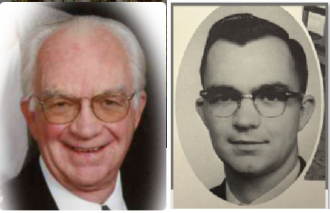

I'm a Christian, and I'm a daughter of Allan B. Holbrook, now in heaven. My married name is Debby Stevens.

About my family:

My parents, Allan and Marie, were devout Christians, and had 10 children. They were both school teachers, but Mom quit teaching at public school after marriage. But both Mom and Dad home-schooled us all - starting when I was in 1st grade - that's when they came to the decision to home-school us.

Dad earned an income through being an English teacher here in Traverse City, for man years.

Dad started some Bible meetings that took place in the homes of friends of ours and in our own. He was the main teacher in it, and it was in a discoursing style - he would talk about spiritual things with the fathers of the families, each time, and all the children of the families would sit and listen to it all.

Dad earned an income through being an English teacher here in Traverse City, for man years.

Dad started some Bible meetings that took place in the homes of friends of ours and in our own. He was the main teacher in it, and it was in a discoursing style - he would talk about spiritual things with the fathers of the families, each time, and all the children of the families would sit and listen to it all.

Interested in the last names:

I'm not following any families.

Updated: February 8, 2025

Message Debby Stevens

Loading...one moment please

Recent Activity

Debby Stevens

shared a photo

Feb 08, 2025 9:49 AM

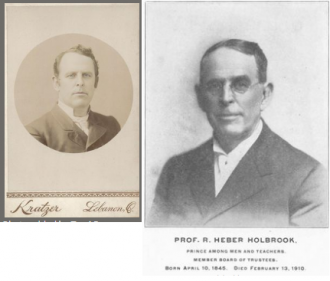

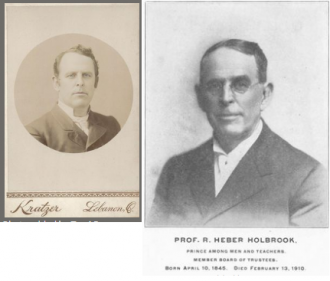

Reginald Heber Holbrook 1845 - 1910 Derby, CT -...

...

...

Debby Stevens

shared a photo

Feb 08, 2025 9:40 AM

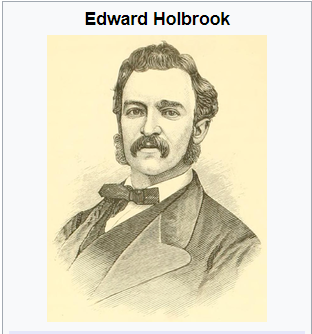

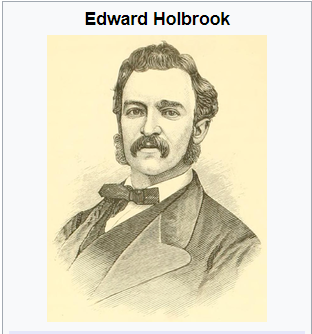

Edward Dexter Holbrook May 6, 1836 – June...

...

...

Debby Stevens

shared a photo

Feb 08, 2025 9:23 AM

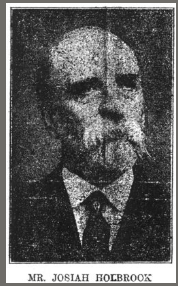

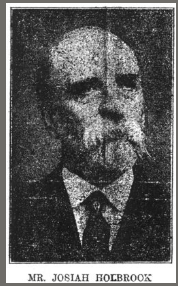

Josiah Holbrook 1788 - 1854 Lebanon, OH

Son of Professor and President of College in...

Son of Professor and President of College in...

Debby Stevens

followed a member

Feb 07, 2025 2:38 AM

Debby Stevens

shared a photo

Feb 07, 2025 2:28 AM

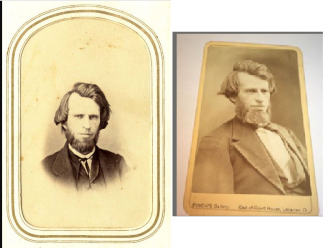

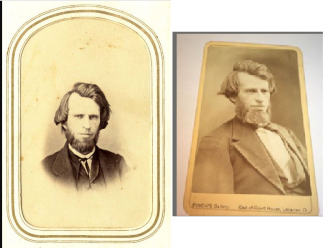

Alfred Holbrook 1816 - 1909 (Professor &...

...

...

Photos Added

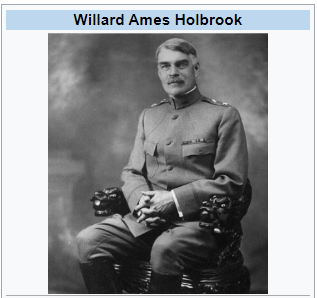

Reginald Heber Holbrook 1845 - 1910 Derby, CT - Pittsburgh, PA

Son of Professor and President of a college in Ohio, Alfred Holbrook,

Son of Professor and President of a college in Ohio, Alfred Holbrook,

Edward Dexter Holbrook May 6, 1836 – June 18, 1870 Elyria, Ohio

Edward Dexter Holbrook May 6, 1836 – June 18, 1870

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations.

Edward Holbrook

Delegate to the

U.S. House of Representatives

from the Idaho Territory's

at-large district

In office

March 4, 1865 – March 3, 1869

Preceded by William H. Wallace

Succeeded by Jacob K. Shafer

Personal details

Born Edward Dexter Holbrook

May 6, 1836

Elyria, Ohio, U.S.

Died June 18, 1870 (aged 34)

Idaho City, Idaho Territory, U.S.

Political party Democratic

Education Oberlin College (LLB)

Edward Dexter Holbrook (May 6, 1836 – June 18, 1870) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a congressional delegate for the Idaho Territory from 1865 to 1869.

Early life and education

Born in Elyria, Ohio, Holbrook attended public schools and earned a Bachelor of Laws from Oberlin College.

Career

He was admitted to the bar in 1859 and practiced law in Elyria, Ohio; Weaverville, California; and Placerville, Idaho.

Holbrook was elected as a Democrat to the 39th and 40th Congresses; serving from (March 4, 1865 - March 3, 1869). He was censured by the United States House of Representatives on February 4, 1869, for use of unparliamentary language and did not stand as a candidate for re-election.

Personal life

Holbrook was shot by Charles H. Douglas in Idaho City, Idaho Territory on June 17, 1870, and died from his wounds the next day. He was interred in the Masonic Burial Ground in that city. Holbrook, Idaho, is named in his honor.

Edward Dexter Holbrook May 6, 1836 – June 18, 1870

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations.

Edward Holbrook

Delegate to the

U.S. House of Representatives

from the Idaho Territory's

at-large district

In office

March 4, 1865 – March 3, 1869

Preceded by William H. Wallace

Succeeded by Jacob K. Shafer

Personal details

Born Edward Dexter Holbrook

May 6, 1836

Elyria, Ohio, U.S.

Died June 18, 1870 (aged 34)

Idaho City, Idaho Territory, U.S.

Political party Democratic

Education Oberlin College (LLB)

Edward Dexter Holbrook (May 6, 1836 – June 18, 1870) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a congressional delegate for the Idaho Territory from 1865 to 1869.

Early life and education

Born in Elyria, Ohio, Holbrook attended public schools and earned a Bachelor of Laws from Oberlin College.

Career

He was admitted to the bar in 1859 and practiced law in Elyria, Ohio; Weaverville, California; and Placerville, Idaho.

Holbrook was elected as a Democrat to the 39th and 40th Congresses; serving from (March 4, 1865 - March 3, 1869). He was censured by the United States House of Representatives on February 4, 1869, for use of unparliamentary language and did not stand as a candidate for re-election.

Personal life

Holbrook was shot by Charles H. Douglas in Idaho City, Idaho Territory on June 17, 1870, and died from his wounds the next day. He was interred in the Masonic Burial Ground in that city. Holbrook, Idaho, is named in his honor.

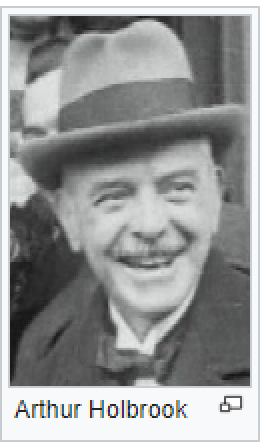

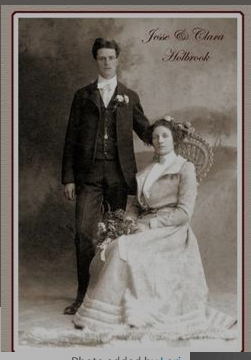

Josiah Holbrook 1788 - 1854 Lebanon, OH

Son of Professor and President of College in Lebanon, OH - Alfred Holbrook, who was born on Feb. 17, 1816.

Alfred Holbrook 1816 - 1909 (Professor & President of college) - Lebanon, OH

PROF. ALFRED HOLBROOK, President of the National Normal University, Lebanon, Ohio; was born in Derby, Conn., Feb. 17, 1816; he was the elder of two sons, the only children of Josiah Holbrook, celebrated as the founder of Teachers’ Institutes, the American Institute of Instruction and the lyceum or lecture system of popular instruction. He lost his mother when three years of age, but was tenderly cared for by several aunts, who faithfully laid a sturdy Christian foundation to his character; his school-days were almost entirely during his first twelve years; her read a chapter from the Bible when 3 years of age, his father giving to the aunt who was his instructor a promised silk dress for teaching him this feat. When about 11 years of age, he went to school to Elizur Wright, at Groton, Mass., where he boarded with the distinguished John Todd, than a Congregational minister of that place. At the age of 13, he went to Boston, where he was employed a year and a half in his father’s manufactory of school apparatus; he was here an indefatigable workman and a most zealous student, his studies being directed by his father. For a watch, promised by his father, if he should accomplish the task, he read Day’s algebra through in three months, very thoroughly, working all the examples; but his work and his study broke his health, and he returned to his native village, where he lived until 17 years of age, when he entered upon his first experience as a teacher, in Monroe, Conn. A year later, he went to New York and engaged for some eighteen months in the manufacture of surveyors’ instruments, he having determined to become an engineer. One of the few requests his father ever denied him was the one to go to Yale College, of which his father was a graduate. The reason assigned was the bad methods and the bad morals

PROF. ALFRED HOLBROOK, President of the National Normal University, Lebanon, Ohio; was born in Derby, Conn., Feb. 17, 1816; he was the elder of two sons, the only children of Josiah Holbrook, celebrated as the founder of Teachers’ Institutes, the American Institute of Instruction and the lyceum or lecture system of popular instruction. He lost his mother when three years of age, but was tenderly cared for by several aunts, who faithfully laid a sturdy Christian foundation to his character; his school-days were almost entirely during his first twelve years; her read a chapter from the Bible when 3 years of age, his father giving to the aunt who was his instructor a promised silk dress for teaching him this feat. When about 11 years of age, he went to school to Elizur Wright, at Groton, Mass., where he boarded with the distinguished John Todd, than a Congregational minister of that place. At the age of 13, he went to Boston, where he was employed a year and a half in his father’s manufactory of school apparatus; he was here an indefatigable workman and a most zealous student, his studies being directed by his father. For a watch, promised by his father, if he should accomplish the task, he read Day’s algebra through in three months, very thoroughly, working all the examples; but his work and his study broke his health, and he returned to his native village, where he lived until 17 years of age, when he entered upon his first experience as a teacher, in Monroe, Conn. A year later, he went to New York and engaged for some eighteen months in the manufacture of surveyors’ instruments, he having determined to become an engineer. One of the few requests his father ever denied him was the one to go to Yale College, of which his father was a graduate. The reason assigned was the bad methods and the bad morals

Recent Comments

Debby's Followers

Debby Stevens

I'm a Christian, and I'm a daughter of Allan B. Holbrook, now in heaven. My married name is Debby Stevens.

My parents, Allan and Marie, were devout Christians, and had 10 children. They were both school teachers, but Mom quit teaching at public school after marriage. But both Mom and Dad home-schooled us all - starting when I was in 1st grade - that's when they came to the decision to home-school us. Dad earned an income through being an English teacher here in Traverse City, for man years. Dad started some Bible meetings that took place in the homes of friends of ours and in our own. He was the main teacher in it, and it was in a discoursing style - he would talk about spiritual things with the fathers of the families, each time, and all the children of the families would sit and listen to it all.

My parents, Allan and Marie, were devout Christians, and had 10 children. They were both school teachers, but Mom quit teaching at public school after marriage. But both Mom and Dad home-schooled us all - starting when I was in 1st grade - that's when they came to the decision to home-school us. Dad earned an income through being an English teacher here in Traverse City, for man years. Dad started some Bible meetings that took place in the homes of friends of ours and in our own. He was the main teacher in it, and it was in a discoursing style - he would talk about spiritual things with the fathers of the families, each time, and all the children of the families would sit and listen to it all.

Lori Russell

My mother is Pamela Thompson. My dad is Richard William Russell.

My mom grew up in Fenwick Michigan. My dad grew up in Hart Michigan. They had 2 kids together. Living in Michigan. I have other Half siblings out there somewhere

My mom grew up in Fenwick Michigan. My dad grew up in Hart Michigan. They had 2 kids together. Living in Michigan. I have other Half siblings out there somewhere

Addie Childers

About me:I haven't shared any details about myself.

Daniel Pinna

I want to build a place where my son can meet his great-grandparents. My grandmother Marian Joyce (Benning) Kroetch always wanted to meet her great-grandchildren, but she died just a handful of years before my son's birth.

So while she didn't have the opportunity to meet him, at least he will be able to know her.

For more information about what we're building see About AncientFaces. For information on the folks who build and support the community see Daniel - Founder & Creator.

My father's side is full blood Sicilian and my mother's side is a combination of Welsh, Scottish, German and a few other European cultures. One of my more colorful (ahem black sheep) family members came over on the Mayflower. He was among the first to be hanged in the New World for a criminal offense he made while onboard the ship.

My father's side is full blood Sicilian and my mother's side is a combination of Welsh, Scottish, German and a few other European cultures. One of my more colorful (ahem black sheep) family members came over on the Mayflower. He was among the first to be hanged in the New World for a criminal offense he made while onboard the ship.

Favorites

Loading...one moment please

Reginald Heber Holbrook 1845 - 1910 Derby, CT - Pittsburgh, PA

Son of Professor and President of a college in Ohio, Alfred Holbrook,

Son of Professor and President of a college in Ohio, Alfred Holbrook,

Edward Dexter Holbrook May 6, 1836 – June 18, 1870 Elyria, Ohio

Edward Dexter Holbrook May 6, 1836 – June 18, 1870

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations.

Edward Holbrook

Delegate to the

U.S. House of Representatives

from the Idaho Territory's

at-large district

In office

March 4, 1865 – March 3, 1869

Preceded by William H. Wallace

Succeeded by Jacob K. Shafer

Personal details

Born Edward Dexter Holbrook

May 6, 1836

Elyria, Ohio, U.S.

Died June 18, 1870 (aged 34)

Idaho City, Idaho Territory, U.S.

Political party Democratic

Education Oberlin College (LLB)

Edward Dexter Holbrook (May 6, 1836 – June 18, 1870) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a congressional delegate for the Idaho Territory from 1865 to 1869.

Early life and education

Born in Elyria, Ohio, Holbrook attended public schools and earned a Bachelor of Laws from Oberlin College.

Career

He was admitted to the bar in 1859 and practiced law in Elyria, Ohio; Weaverville, California; and Placerville, Idaho.

Holbrook was elected as a Democrat to the 39th and 40th Congresses; serving from (March 4, 1865 - March 3, 1869). He was censured by the United States House of Representatives on February 4, 1869, for use of unparliamentary language and did not stand as a candidate for re-election.

Personal life

Holbrook was shot by Charles H. Douglas in Idaho City, Idaho Territory on June 17, 1870, and died from his wounds the next day. He was interred in the Masonic Burial Ground in that city. Holbrook, Idaho, is named in his honor.

Edward Dexter Holbrook May 6, 1836 – June 18, 1870

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations.

Edward Holbrook

Delegate to the

U.S. House of Representatives

from the Idaho Territory's

at-large district

In office

March 4, 1865 – March 3, 1869

Preceded by William H. Wallace

Succeeded by Jacob K. Shafer

Personal details

Born Edward Dexter Holbrook

May 6, 1836

Elyria, Ohio, U.S.

Died June 18, 1870 (aged 34)

Idaho City, Idaho Territory, U.S.

Political party Democratic

Education Oberlin College (LLB)

Edward Dexter Holbrook (May 6, 1836 – June 18, 1870) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a congressional delegate for the Idaho Territory from 1865 to 1869.

Early life and education

Born in Elyria, Ohio, Holbrook attended public schools and earned a Bachelor of Laws from Oberlin College.

Career

He was admitted to the bar in 1859 and practiced law in Elyria, Ohio; Weaverville, California; and Placerville, Idaho.

Holbrook was elected as a Democrat to the 39th and 40th Congresses; serving from (March 4, 1865 - March 3, 1869). He was censured by the United States House of Representatives on February 4, 1869, for use of unparliamentary language and did not stand as a candidate for re-election.

Personal life

Holbrook was shot by Charles H. Douglas in Idaho City, Idaho Territory on June 17, 1870, and died from his wounds the next day. He was interred in the Masonic Burial Ground in that city. Holbrook, Idaho, is named in his honor.

Josiah Holbrook 1788 - 1854 Lebanon, OH

Son of Professor and President of College in Lebanon, OH - Alfred Holbrook, who was born on Feb. 17, 1816.

Debby Stevens

I'm a Christian, and I'm a daughter of Allan B. Holbrook, now in heaven. My married name is Debby Stevens.

My parents, Allan and Marie, were devout Christians, and had 10 children. They were both school teachers, but Mom quit teaching at public school after marriage. But both Mom and Dad home-schooled us all - starting when I was in 1st grade - that's when they came to the decision to home-school us. Dad earned an income through being an English teacher here in Traverse City, for man years. Dad started some Bible meetings that took place in the homes of friends of ours and in our own. He was the main teacher in it, and it was in a discoursing style - he would talk about spiritual things with the fathers of the families, each time, and all the children of the families would sit and listen to it all.

My parents, Allan and Marie, were devout Christians, and had 10 children. They were both school teachers, but Mom quit teaching at public school after marriage. But both Mom and Dad home-schooled us all - starting when I was in 1st grade - that's when they came to the decision to home-school us. Dad earned an income through being an English teacher here in Traverse City, for man years. Dad started some Bible meetings that took place in the homes of friends of ours and in our own. He was the main teacher in it, and it was in a discoursing style - he would talk about spiritual things with the fathers of the families, each time, and all the children of the families would sit and listen to it all.

Alfred Holbrook 1816 - 1909 (Professor & President of college) - Lebanon, OH

PROF. ALFRED HOLBROOK, President of the National Normal University, Lebanon, Ohio; was born in Derby, Conn., Feb. 17, 1816; he was the elder of two sons, the only children of Josiah Holbrook, celebrated as the founder of Teachers’ Institutes, the American Institute of Instruction and the lyceum or lecture system of popular instruction. He lost his mother when three years of age, but was tenderly cared for by several aunts, who faithfully laid a sturdy Christian foundation to his character; his school-days were almost entirely during his first twelve years; her read a chapter from the Bible when 3 years of age, his father giving to the aunt who was his instructor a promised silk dress for teaching him this feat. When about 11 years of age, he went to school to Elizur Wright, at Groton, Mass., where he boarded with the distinguished John Todd, than a Congregational minister of that place. At the age of 13, he went to Boston, where he was employed a year and a half in his father’s manufactory of school apparatus; he was here an indefatigable workman and a most zealous student, his studies being directed by his father. For a watch, promised by his father, if he should accomplish the task, he read Day’s algebra through in three months, very thoroughly, working all the examples; but his work and his study broke his health, and he returned to his native village, where he lived until 17 years of age, when he entered upon his first experience as a teacher, in Monroe, Conn. A year later, he went to New York and engaged for some eighteen months in the manufacture of surveyors’ instruments, he having determined to become an engineer. One of the few requests his father ever denied him was the one to go to Yale College, of which his father was a graduate. The reason assigned was the bad methods and the bad morals

PROF. ALFRED HOLBROOK, President of the National Normal University, Lebanon, Ohio; was born in Derby, Conn., Feb. 17, 1816; he was the elder of two sons, the only children of Josiah Holbrook, celebrated as the founder of Teachers’ Institutes, the American Institute of Instruction and the lyceum or lecture system of popular instruction. He lost his mother when three years of age, but was tenderly cared for by several aunts, who faithfully laid a sturdy Christian foundation to his character; his school-days were almost entirely during his first twelve years; her read a chapter from the Bible when 3 years of age, his father giving to the aunt who was his instructor a promised silk dress for teaching him this feat. When about 11 years of age, he went to school to Elizur Wright, at Groton, Mass., where he boarded with the distinguished John Todd, than a Congregational minister of that place. At the age of 13, he went to Boston, where he was employed a year and a half in his father’s manufactory of school apparatus; he was here an indefatigable workman and a most zealous student, his studies being directed by his father. For a watch, promised by his father, if he should accomplish the task, he read Day’s algebra through in three months, very thoroughly, working all the examples; but his work and his study broke his health, and he returned to his native village, where he lived until 17 years of age, when he entered upon his first experience as a teacher, in Monroe, Conn. A year later, he went to New York and engaged for some eighteen months in the manufacture of surveyors’ instruments, he having determined to become an engineer. One of the few requests his father ever denied him was the one to go to Yale College, of which his father was a graduate. The reason assigned was the bad methods and the bad morals

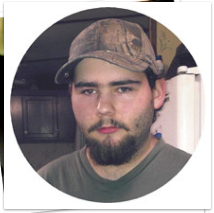

Thomas Lydell Holbrook 1955 - 2017 Sandy Hook, KY -Lexington, KY

!/Obituary

Obituary for Thomas Lydell Holbrook

Thomas Lydell Holbrook age 21, of Lexington, Kentucky formerly of Sandy Hook, passed away Tuesday, November 07, 2017 in Lexington, Kentucky.

He was born October 29, 1996 in Morehead, Kentucky a son of Rodney Holbrook and Stacy Mauk Salyers.

Thomas was of the Baptist Faith. He worked at the Toyota Plant in Lexington, Kentucky. He enjoyed hunting, fishing, working on his car and truck, spending time with his family and friends.

He is preceded in death by his paternal grandfather, Paul Holbrook; maternal grandmother, Dazel Mauk.

In addition to his parents he is survived by his step father, Paul Salyers of Sandy Hook, Kentucky; two brothers, Rodney Holbrook Jr. and Austin Holbrook, both of Sandy Hook, Kentucky; two step brothers, Hayden Salyers and Joshua Clyde Salyers; paternal grandmother, Laura (Charlie) Skaggs of Olive Hill, Kentucky; maternal grandfather, Charlie Mauk of Sandy Hook, Kentucky; one nephew, Colton Holbrook; his best friend, Josh Bayless.

Funeral services will be held 1 pm Friday, November 10, 2017 in the Chapel of Waddell & Whitt Funeral Home with Brother Darren Barker officiating. Burial will follow in the Holbrook Family Cemetery on Garris Ridge.

Friends may visit after 6 pm on Thursday and after 9 am on Friday until the service hour at the funeral home.

Pallbearers: Rodney Holbrook, Rodney Holbrook Jr., Austin Holbrook, Josh Bayless, Albert Holbrook and James Holbrook.

Honorary Pallbearers: Paul Salyers and William Gollihue.

To send flowers or a memorial gift to the family of Thomas Lydell Holbrook please visit our Sympathy Store.

Obituary for Thomas Lydell Holbrook

Thomas Lydell Holbrook age 21, of Lexington, Kentucky formerly of Sandy Hook, passed away Tuesday, November 07, 2017 in Lexington, Kentucky.

He was born October 29, 1996 in Morehead, Kentucky a son of Rodney Holbrook and Stacy Mauk Salyers.

Thomas was of the Baptist Faith. He worked at the Toyota Plant in Lexington, Kentucky. He enjoyed hunting, fishing, working on his car and truck, spending time with his family and friends.

He is preceded in death by his paternal grandfather, Paul Holbrook; maternal grandmother, Dazel Mauk.

In addition to his parents he is survived by his step father, Paul Salyers of Sandy Hook, Kentucky; two brothers, Rodney Holbrook Jr. and Austin Holbrook, both of Sandy Hook, Kentucky; two step brothers, Hayden Salyers and Joshua Clyde Salyers; paternal grandmother, Laura (Charlie) Skaggs of Olive Hill, Kentucky; maternal grandfather, Charlie Mauk of Sandy Hook, Kentucky; one nephew, Colton Holbrook; his best friend, Josh Bayless.

Funeral services will be held 1 pm Friday, November 10, 2017 in the Chapel of Waddell & Whitt Funeral Home with Brother Darren Barker officiating. Burial will follow in the Holbrook Family Cemetery on Garris Ridge.

Friends may visit after 6 pm on Thursday and after 9 am on Friday until the service hour at the funeral home.

Pallbearers: Rodney Holbrook, Rodney Holbrook Jr., Austin Holbrook, Josh Bayless, Albert Holbrook and James Holbrook.

Honorary Pallbearers: Paul Salyers and William Gollihue.

To send flowers or a memorial gift to the family of Thomas Lydell Holbrook please visit our Sympathy Store.

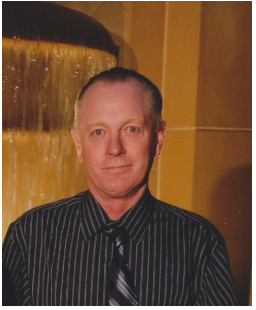

Robert Holbrook 1926 - 2016 Olive Hill, KY - Elgin, KY

Robert “Bob” Holbrook, Jr., age 90, passed away Monday, October 10, 2016 at Sherman Hospital in Elgin surrounded by family.

He was born July 19, 1926 in Olive Hill, Kentucky, the son of James and Mary (Howard) Holbrook.

Robert served his country in the US Army during WW II. He worked for Globe Union in Geneva for many years and later owned and operated the LaFox Lounge in South Elgin. Robert enjoyed woodworking and was very artistic and creative. He was a master story teller and enjoyed spending time with his family and friends. Robert will be greatly missed by all those who knew him, especially his beloved dog, Penny

He is survived by his children James “Butch” (Debbie) of Ohio, Alice (Bob) Owens of Pennsylvania, Fred of Ohio and Lisa Holbrook of East Dundee; 19 grandchildren; 37 great grandchildren; 26 great great grandchildren; sister Juanita Nickell of Ohio; and many other dear relatives and friends.

Robert was preceded in death by his parents, son John, daughter Roberta, nine siblings, grandsons Don Francis and Robert “Bobby” Owens, his children’s mother Darlene (Tomlin) who passed away in 2003 and devoted wife Bernadine who passed away in 2009.

Visitation will be held Friday, October 14 from 4:00-8:00 pm at Malone Funeral Home, 324 East State Street (Rt 38), Geneva.

Funeral service for Robert will be held Saturday, October 15, 2016 at 10:00 am at Malone Funeral Home.

Burial will follow at River Hills Memorial Park, Batavia.

In lieu of flowers, memorials to American Lung Association, 3000 Kelly Lane, Springfield, Illinois 62711 will be appreciated.

For information 630-232-8233.

Robert “Bob” Holbrook, Jr., age 90, passed away Monday, October 10, 2016 at Sherman Hospital in Elgin surrounded by family.

He was born July 19, 1926 in Olive Hill, Kentucky, the son of James and Mary (Howard) Holbrook.

Robert served his country in the US Army during WW II. He worked for Globe Union in Geneva for many years and later owned and operated the LaFox Lounge in South Elgin. Robert enjoyed woodworking and was very artistic and creative. He was a master story teller and enjoyed spending time with his family and friends. Robert will be greatly missed by all those who knew him, especially his beloved dog, Penny

He is survived by his children James “Butch” (Debbie) of Ohio, Alice (Bob) Owens of Pennsylvania, Fred of Ohio and Lisa Holbrook of East Dundee; 19 grandchildren; 37 great grandchildren; 26 great great grandchildren; sister Juanita Nickell of Ohio; and many other dear relatives and friends.

Robert was preceded in death by his parents, son John, daughter Roberta, nine siblings, grandsons Don Francis and Robert “Bobby” Owens, his children’s mother Darlene (Tomlin) who passed away in 2003 and devoted wife Bernadine who passed away in 2009.

Visitation will be held Friday, October 14 from 4:00-8:00 pm at Malone Funeral Home, 324 East State Street (Rt 38), Geneva.

Funeral service for Robert will be held Saturday, October 15, 2016 at 10:00 am at Malone Funeral Home.

Burial will follow at River Hills Memorial Park, Batavia.

In lieu of flowers, memorials to American Lung Association, 3000 Kelly Lane, Springfield, Illinois 62711 will be appreciated.

For information 630-232-8233.

Charles R. Holbrook Jr. 1958 - 2014 Madison, IN

Charles R. Holbrook, Jr. "Chuck", 55, of Madison IN, passed away Saturday, April 19, 2014. He was a forklift operator with Madison Prescision Products.

He was preceded in death by his father, Charles Holbrook, Sr. & the love of his life, Rhonda Mitchell.

Survived by his son, Jared Holbrook, mother, Carolyn Holbrook & his brother, Jeff Holbrook (Nelsonya)

Funeral services will be 11AM Thursday at Fairdale-McDaniel Funeral Home 411 Fairdale Rd.

Burial to follow. Visitation will be 2-8PM Wednesday at the funeral home.

Charles R. Holbrook, Jr. "Chuck", 55, of Madison IN, passed away Saturday, April 19, 2014. He was a forklift operator with Madison Prescision Products.

He was preceded in death by his father, Charles Holbrook, Sr. & the love of his life, Rhonda Mitchell.

Survived by his son, Jared Holbrook, mother, Carolyn Holbrook & his brother, Jeff Holbrook (Nelsonya)

Funeral services will be 11AM Thursday at Fairdale-McDaniel Funeral Home 411 Fairdale Rd.

Burial to follow. Visitation will be 2-8PM Wednesday at the funeral home.

Leroy Holbrook 1927 - 2014 Kentucky - Ohio

A funeral service for Leroy Holbrook will be held on Thursday August 7, 2014 at 10:00 AM at the Kauber Sammons Funeral Home. Interment will be held at Forest Lawn Memorial Gardens with Pastor Tom Myers officiating. Military honors will be provided by the Reynoldsburg VFW.

Leroy was born in Lewis County, Kentucky on October 14, 1927 to the late Lonzy and Atha (Holcomb) Holbrook. He died on Thursday July 31, 2014 at the Kindred Health Care Center in Newark. He was 86.

Mr. Holbrook served his country in the United States Air Force, was a member of the American Legion Post 107, a longtime NRA member, an avid collector and an avid outdoorsman. He worked for the Owens Illinois Glass Company.

He is preceded in death by his wife of 58 years Senneth Ione (Hatfield), stepdaughter Mary Greene and his brother Ed Holbrook.

Leroy is survived by his son-in-law Richard Greene, grandchildren John (Cathy), Rick (Alison), great grandchildren Allison, Cheyenne, Shawntae, Brittany and Carson, great-great granddaughter Scotland, his sister Elaine Fieldman and other family members residing in Ohio, Michigan and Kentucky.

Friends may call Wednesday at the funeral home from 5:00 pm to 8:00 pm. An online memorial will be at www.kaubersammons.com. Friends may, if they wish, donate to the hospice of their choice in his memory.

A funeral service for Leroy Holbrook will be held on Thursday August 7, 2014 at 10:00 AM at the Kauber Sammons Funeral Home. Interment will be held at Forest Lawn Memorial Gardens with Pastor Tom Myers officiating. Military honors will be provided by the Reynoldsburg VFW.

Leroy was born in Lewis County, Kentucky on October 14, 1927 to the late Lonzy and Atha (Holcomb) Holbrook. He died on Thursday July 31, 2014 at the Kindred Health Care Center in Newark. He was 86.

Mr. Holbrook served his country in the United States Air Force, was a member of the American Legion Post 107, a longtime NRA member, an avid collector and an avid outdoorsman. He worked for the Owens Illinois Glass Company.

He is preceded in death by his wife of 58 years Senneth Ione (Hatfield), stepdaughter Mary Greene and his brother Ed Holbrook.

Leroy is survived by his son-in-law Richard Greene, grandchildren John (Cathy), Rick (Alison), great grandchildren Allison, Cheyenne, Shawntae, Brittany and Carson, great-great granddaughter Scotland, his sister Elaine Fieldman and other family members residing in Ohio, Michigan and Kentucky.

Friends may call Wednesday at the funeral home from 5:00 pm to 8:00 pm. An online memorial will be at www.kaubersammons.com. Friends may, if they wish, donate to the hospice of their choice in his memory.

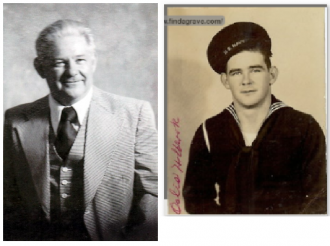

Odis Holbrook 1925 - 2015 Maypearl, TX - Houston, TX

Odis Holbrook peacefully passed away on Thursday, February 19, 2015 at the age of 91. Mr. Holbrook was born January 14, 1924 in Maypearl, Texas to Calpalkcus and Ona (Jackson) Holbrook. Following the death of his mother in September 1924, he was taken in and raised by his uncle and aunt, Harvey and Susie (Jackson) Brigman. He served in the United States Navy during World War II. After the war, Odis moved to Houston and worked at Shell Oil Refinery in Deer Park, Texas until his retirement in 1986. He was preceded in death by his parents; brothers GHL Holbrook, Alton C. Holbrook and Onas (Blackie) Holbrook; daughter-in-law Lora Ann Holbrook; son-in-law Tony Ray Hallman; and his beloved wife of 62 years, Carmella (Bernard) Holbrook. His survivors include son Michael O. Holbrook of Rome, New York; daughter and son-in-law Maurine and Tom Schellinger of Spring, Texas; daughter Tammy Hallman of Dayton, Texas; grandchildren Michael A. Schellinger, Stephen Schellinger and wife Kari Rae, Patrick Schellinger and wife Emily, Ted Holbrook, Jeffery Schellinger, Joy Holbrook; and great-grandchildren Christopher Schellinger Jensen and Liam Schellinger. He is also survived by his sister Maurine Wood; brother Jack Holbrook of Dallas, Texas; and numerous nieces and nephews.

A visitation will be held at 9:00 a.m. on Monday, February 23, 2015 at Forest Park East Funeral Home with a funeral service beginning at 10:00 a.m. Interment will follow at Forest Park East Cemetery.

In lieu of flowers, the family requests that donations be made to Fisher House Foundation, Inc.

Odis Holbrook peacefully passed away on Thursday, February 19, 2015 at the age of 91. Mr. Holbrook was born January 14, 1924 in Maypearl, Texas to Calpalkcus and Ona (Jackson) Holbrook. Following the death of his mother in September 1924, he was taken in and raised by his uncle and aunt, Harvey and Susie (Jackson) Brigman. He served in the United States Navy during World War II. After the war, Odis moved to Houston and worked at Shell Oil Refinery in Deer Park, Texas until his retirement in 1986. He was preceded in death by his parents; brothers GHL Holbrook, Alton C. Holbrook and Onas (Blackie) Holbrook; daughter-in-law Lora Ann Holbrook; son-in-law Tony Ray Hallman; and his beloved wife of 62 years, Carmella (Bernard) Holbrook. His survivors include son Michael O. Holbrook of Rome, New York; daughter and son-in-law Maurine and Tom Schellinger of Spring, Texas; daughter Tammy Hallman of Dayton, Texas; grandchildren Michael A. Schellinger, Stephen Schellinger and wife Kari Rae, Patrick Schellinger and wife Emily, Ted Holbrook, Jeffery Schellinger, Joy Holbrook; and great-grandchildren Christopher Schellinger Jensen and Liam Schellinger. He is also survived by his sister Maurine Wood; brother Jack Holbrook of Dallas, Texas; and numerous nieces and nephews.

A visitation will be held at 9:00 a.m. on Monday, February 23, 2015 at Forest Park East Funeral Home with a funeral service beginning at 10:00 a.m. Interment will follow at Forest Park East Cemetery.

In lieu of flowers, the family requests that donations be made to Fisher House Foundation, Inc.

Larry D. Holbrook 1937 - 2015 Lancaster, PA

Larry D. Holbrook, 78 of Lancaster, died Tuesday August 4, 2015 at Arbors at Carroll. He was a US Army Veteran and attended the First United Methodist Church, Lancaster.

He was preceded in death by his wife, Iona M. “Onie” Holbrook; parents, Manzel and Anise Holbrook.

He is survived by his son and daughter-in-law, Terry and Jennifer Holbrook, three grandchildren, Zachary, Abigail and Coleton Holbrook all of Lancaster; brother, Michael (Debbie) Holbrook, sisters, Patricia (Dave) Nicholls and Mary Ellen (Bill) Moder; nieces and nephews.

Funeral services will be held 10:00 a.m. Friday at the Halteman-Fett & Dyer Funeral Home with Rev. Cheryl Foulk officiating. Burial will be at Knollwood Cemetery, Logan. Friends may call Thursday from 5-8 p.m. at the funeral home.

The family suggests contributions to: First United Methodist Church, 163 East Wheeling Street, Lancaster, Ohio 43130.

Larry D. Holbrook, 78 of Lancaster, died Tuesday August 4, 2015 at Arbors at Carroll. He was a US Army Veteran and attended the First United Methodist Church, Lancaster.

He was preceded in death by his wife, Iona M. “Onie” Holbrook; parents, Manzel and Anise Holbrook.

He is survived by his son and daughter-in-law, Terry and Jennifer Holbrook, three grandchildren, Zachary, Abigail and Coleton Holbrook all of Lancaster; brother, Michael (Debbie) Holbrook, sisters, Patricia (Dave) Nicholls and Mary Ellen (Bill) Moder; nieces and nephews.

Funeral services will be held 10:00 a.m. Friday at the Halteman-Fett & Dyer Funeral Home with Rev. Cheryl Foulk officiating. Burial will be at Knollwood Cemetery, Logan. Friends may call Thursday from 5-8 p.m. at the funeral home.

The family suggests contributions to: First United Methodist Church, 163 East Wheeling Street, Lancaster, Ohio 43130.

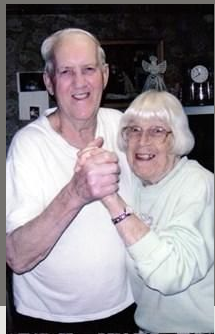

George W. Holbrook 1923 - 2020 Lawrence, KY - Alexandria, OH

George W. Holbrook, passed away Tuesday, February 25, 2020 at his home in Alexandria, OH. He was born October 24, 1923 in Lawrence Co., KY to the late Morton and Hattie Marie (Rogers) Holbrook. George worked as a farmer and brick layer for 60 years. Outside of work George loved to farm, raising his cattle, hunting, and also watching and attending NASCAR races. George attended the first Daytona 500 in 1959 and his last Daytona 500 at the age of 91. He was a faithful member of the Alexandria Baptist Church. George married his wife Carol, September 17, 1983 at the childhood home of his mother by the well where his father had proposed to her at in Cherokee, KY. George is survived by his loving wife Carol Holbrook; daughter Karen (John) Wingo; son George D. (Linda) Holbrook; grandchildren, Ricky Carr, Mindi (Mike) Sileargy, Cory (Jody) Holbrook, Jason (Mary) Evans; great-grandchildren Jerrad, Nick, Baylee, Christian, AJ, Alyssa, Elena, Isabella, and Michael; sister Martha Adams, the survior of 11 siblings; former wife Wanda Holbrook; and many nieces and nephews. Calling hours for George will be held Monday, March 02, 2020 from 5:00-8:00 pm at CROUSE-KAUBER-FRALERY FUNERAL HOME 225 N. Main St. Johnstown, OH 43031. The funeral service will be held 12:00 pm Tuesday March 03, 2020 at the funeral home, with burial to immediately follow at Maple Grove Cemetery in Alexandria, OH. Officiating the services will be Pastor Brian Potts. In lieu of flowers memorial contributions can be made to the St. Albans Township Fire Department.

George W. Holbrook, passed away Tuesday, February 25, 2020 at his home in Alexandria, OH. He was born October 24, 1923 in Lawrence Co., KY to the late Morton and Hattie Marie (Rogers) Holbrook. George worked as a farmer and brick layer for 60 years. Outside of work George loved to farm, raising his cattle, hunting, and also watching and attending NASCAR races. George attended the first Daytona 500 in 1959 and his last Daytona 500 at the age of 91. He was a faithful member of the Alexandria Baptist Church. George married his wife Carol, September 17, 1983 at the childhood home of his mother by the well where his father had proposed to her at in Cherokee, KY. George is survived by his loving wife Carol Holbrook; daughter Karen (John) Wingo; son George D. (Linda) Holbrook; grandchildren, Ricky Carr, Mindi (Mike) Sileargy, Cory (Jody) Holbrook, Jason (Mary) Evans; great-grandchildren Jerrad, Nick, Baylee, Christian, AJ, Alyssa, Elena, Isabella, and Michael; sister Martha Adams, the survior of 11 siblings; former wife Wanda Holbrook; and many nieces and nephews. Calling hours for George will be held Monday, March 02, 2020 from 5:00-8:00 pm at CROUSE-KAUBER-FRALERY FUNERAL HOME 225 N. Main St. Johnstown, OH 43031. The funeral service will be held 12:00 pm Tuesday March 03, 2020 at the funeral home, with burial to immediately follow at Maple Grove Cemetery in Alexandria, OH. Officiating the services will be Pastor Brian Potts. In lieu of flowers memorial contributions can be made to the St. Albans Township Fire Department.

Wilbur Lee Holbrook 1929 - 2021 Redush, KY - Port Richey, FL

Wilbur Lee Holbrook, 92, passed April 15, 2021 at HPH Hospice in Brooksville, Florida. Wilbur was born January 30, 1929, in Redbush, Kentucky, the son of Ernest Eli and Zella Elizabeth Holbrook (Kelly). He was the oldest of two sons. He is survived by one brother, William, of Jeffersonville, Indiana, one son, Anthony and his wife Deborah, and many nieces ands nephews. On September 3, 1949 he married Wanda Holbrook, of Flat Gap, KY. They lived in the town of Paintsville and Wilbur taught the 6th grade on an emergency teaching certificate. In 1950 he was drafted into the Marine Corps. In 1951 they welcomed Terry Lynn into the family. Terry lived only six months because of Spina Bifida. Dad was discharged from the military in 1952. They moved to Dayton, Ohio where he got a position as a chemist at Frigidaire Division of General Motors.

In 1953, Wilbur and Wanda welcomed a son into their family, Anthony Wilbur. Wilbur continued to work for General Motors until 1957, when he decided to move back to Kentucky and continue his studies at Morehead State University in Morehead. He received his Bachelor of Arts in Education in 1960. He received a teaching position at Wayne Township Public Schools (now Huber Heights) and was a sixth grade teacher for 5 years.

After receiving his Masters Degree from Wittenberg University in Springfield, Ohio, he was asked to take the position of Curriculum Coordinator for Montgomery County (Ohio) Schools. He worked in this position until he retired after 30+ years in education in Ohio.

In 1985 the family moved to New Port Richey, Florida. There was no retirement for Wilbur. In a little more than a month he accepted a teaching position in Pasco County. He worked as a teacher for 10 years before retiring a second time.

Wilbur and Wanda worked as food pantry leaders at First Presbyterian Church, of Port Richey, for many years. He also was deacon and an elder for many years. They were always volunteering at First and Later at Grace Presbyterian in Spring Hill.

Wilbur was known for always having a smile and a clever quip for any occasion. He never met a stranger and was there to help anyone in need. He will be missed by his family, his friends at Brookdale Senior Living in Spring Hill, and his many friends and neighbors past and present.

Wilbur Lee Holbrook, 92, passed April 15, 2021 at HPH Hospice in Brooksville, Florida. Wilbur was born January 30, 1929, in Redbush, Kentucky, the son of Ernest Eli and Zella Elizabeth Holbrook (Kelly). He was the oldest of two sons. He is survived by one brother, William, of Jeffersonville, Indiana, one son, Anthony and his wife Deborah, and many nieces ands nephews. On September 3, 1949 he married Wanda Holbrook, of Flat Gap, KY. They lived in the town of Paintsville and Wilbur taught the 6th grade on an emergency teaching certificate. In 1950 he was drafted into the Marine Corps. In 1951 they welcomed Terry Lynn into the family. Terry lived only six months because of Spina Bifida. Dad was discharged from the military in 1952. They moved to Dayton, Ohio where he got a position as a chemist at Frigidaire Division of General Motors.

In 1953, Wilbur and Wanda welcomed a son into their family, Anthony Wilbur. Wilbur continued to work for General Motors until 1957, when he decided to move back to Kentucky and continue his studies at Morehead State University in Morehead. He received his Bachelor of Arts in Education in 1960. He received a teaching position at Wayne Township Public Schools (now Huber Heights) and was a sixth grade teacher for 5 years.

After receiving his Masters Degree from Wittenberg University in Springfield, Ohio, he was asked to take the position of Curriculum Coordinator for Montgomery County (Ohio) Schools. He worked in this position until he retired after 30+ years in education in Ohio.

In 1985 the family moved to New Port Richey, Florida. There was no retirement for Wilbur. In a little more than a month he accepted a teaching position in Pasco County. He worked as a teacher for 10 years before retiring a second time.

Wilbur and Wanda worked as food pantry leaders at First Presbyterian Church, of Port Richey, for many years. He also was deacon and an elder for many years. They were always volunteering at First and Later at Grace Presbyterian in Spring Hill.

Wilbur was known for always having a smile and a clever quip for any occasion. He never met a stranger and was there to help anyone in need. He will be missed by his family, his friends at Brookdale Senior Living in Spring Hill, and his many friends and neighbors past and present.

Homer Emory Holbrook - Cherokee, GA - Lakeland, FL

Official Obituary of

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook

March 7, 1924 - March 24, 2024

Pause Video

Share Obituary:

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook 31062708

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook

Obituary & Events

Tribute Wall

7 Trees, Flowers, or Condolences have been sent in support of Homer's family - View on Tribute Wall

7 New Posts

Share a memory

Type here to share a memory of Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook or send condolences to the family…

Photos/Video

Candle

Mementos

Post Now

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook Obituary

H. Emory “Em” Holbrook, 100, of Lakeland, Florida passed away Sunday, March 24, 2024. He was born to Alfred S. Holbrook, Sr. and Bessie Bagwell Holbrook in Cherokee County, Georgia on Friday, March 7, 1924.

Em is preceded in death by his parents; wife of 54 years, Dorothy Livingston Holbrook; daughter, Sandra, 4 adult brothers, 2 adult sisters and 4 infant sisters. He is survived by his son and daughter-in-law, Jere and Beverly Holbrook; granddaughter, Lori and Richard Wilkins; grandson, Jason and Amy Holbrook; great granddaughters, Taylor (Jake) Green, Makinsy Wendel, Delaney Wilkins, Kendall Holbrook, Lauren Holbrook, and Peyton Holbrook; 2 sisters-in-law, numerous nieces, nephews, and their children.

Em served his country during W.W. II in the United States Army. He was a participant in the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. He was shot a few weeks later near St. Lo France. Emory was awarded the Purple Heart for his injury. He worked for Delta Air Lines in Atlanta as an airline jet engine mechanic for 28 years before retiring.

Funeral service will be held Monday, April 1, 2024, in the Chapel of Mowell Funeral Home, Fayetteville at 2:00 PM with Pastor John Christopher officiating. Visitation will occur prior to the service from 1:00 to 2:00 PM at the funeral home. Em will be laid to rest at Westminster Memorial Gardens in Peachtree City.

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made in Emory’s honor to :Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, 1 Billy Graham Parkway, Charlotte, North Carolina, 28201-0001 or Good Shepherd Hospice, 3470 Lakeland Hills Blvd., Lakeland, Florida, 33805 / chaptershealth.org/locations/Lakeland-resource-center-good-shepherd-hospice-administrative-office/

We welcome you to leave your condolences, thoughts, and memories of Emory on our Tribute Wall.

Mowell Funeral Home & Cremation Service, Fayetteville, www.mowells.com

To send flowers to the family or plant a tree in memory of Homer, please visit our floral store.

Official Obituary of

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook

March 7, 1924 - March 24, 2024

Pause Video

Share Obituary:

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook 31062708

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook

Obituary & Events

Tribute Wall

7 Trees, Flowers, or Condolences have been sent in support of Homer's family - View on Tribute Wall

7 New Posts

Share a memory

Type here to share a memory of Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook or send condolences to the family…

Photos/Video

Candle

Mementos

Post Now

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook Obituary

H. Emory “Em” Holbrook, 100, of Lakeland, Florida passed away Sunday, March 24, 2024. He was born to Alfred S. Holbrook, Sr. and Bessie Bagwell Holbrook in Cherokee County, Georgia on Friday, March 7, 1924.

Em is preceded in death by his parents; wife of 54 years, Dorothy Livingston Holbrook; daughter, Sandra, 4 adult brothers, 2 adult sisters and 4 infant sisters. He is survived by his son and daughter-in-law, Jere and Beverly Holbrook; granddaughter, Lori and Richard Wilkins; grandson, Jason and Amy Holbrook; great granddaughters, Taylor (Jake) Green, Makinsy Wendel, Delaney Wilkins, Kendall Holbrook, Lauren Holbrook, and Peyton Holbrook; 2 sisters-in-law, numerous nieces, nephews, and their children.

Em served his country during W.W. II in the United States Army. He was a participant in the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. He was shot a few weeks later near St. Lo France. Emory was awarded the Purple Heart for his injury. He worked for Delta Air Lines in Atlanta as an airline jet engine mechanic for 28 years before retiring.

Funeral service will be held Monday, April 1, 2024, in the Chapel of Mowell Funeral Home, Fayetteville at 2:00 PM with Pastor John Christopher officiating. Visitation will occur prior to the service from 1:00 to 2:00 PM at the funeral home. Em will be laid to rest at Westminster Memorial Gardens in Peachtree City.

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made in Emory’s honor to :Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, 1 Billy Graham Parkway, Charlotte, North Carolina, 28201-0001 or Good Shepherd Hospice, 3470 Lakeland Hills Blvd., Lakeland, Florida, 33805 / chaptershealth.org/locations/Lakeland-resource-center-good-shepherd-hospice-administrative-office/

We welcome you to leave your condolences, thoughts, and memories of Emory on our Tribute Wall.

Mowell Funeral Home & Cremation Service, Fayetteville, www.mowells.com

To send flowers to the family or plant a tree in memory of Homer, please visit our floral store.

Homer Emory Holbrook - Cherokee, GA - Lakeland, FL

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook

March 7, 1924 - March 24, 2024

Pause Video

Share Obituary:

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook 31062708

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook

Obituary & Events

Tribute Wall

7 Trees, Flowers, or Condolences have been sent in support of Homer's family - View on Tribute Wall

7 New Posts

Share a memory

Type here to share a memory of Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook or send condolences to the family…

Photos/Video

Candle

Mementos

Post Now

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook Obituary

H. Emory “Em” Holbrook, 100, of Lakeland, Florida passed away Sunday, March 24, 2024. He was born to Alfred S. Holbrook, Sr. and Bessie Bagwell Holbrook in Cherokee County, Georgia on Friday, March 7, 1924.

Em is preceded in death by his parents; wife of 54 years, Dorothy Livingston Holbrook; daughter, Sandra, 4 adult brothers, 2 adult sisters and 4 infant sisters. He is survived by his son and daughter-in-law, Jere and Beverly Holbrook; granddaughter, Lori and Richard Wilkins; grandson, Jason and Amy Holbrook; great granddaughters, Taylor (Jake) Green, Makinsy Wendel, Delaney Wilkins, Kendall Holbrook, Lauren Holbrook, and Peyton Holbrook; 2 sisters-in-law, numerous nieces, nephews, and their children.

Em served his country during W.W. II in the United States Army. He was a participant in the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. He was shot a few weeks later near St. Lo France. Emory was awarded the Purple Heart for his injury. He worked for Delta Air Lines in Atlanta as an airline jet engine mechanic for 28 years before retiring.

Funeral service will be held Monday, April 1, 2024, in the Chapel of Mowell Funeral Home, Fayetteville at 2:00 PM with Pastor John Christopher officiating. Visitation will occur prior to the service from 1:00 to 2:00 PM at the funeral home. Em will be laid to rest at Westminster Memorial Gardens in Peachtree City.

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made in Emory’s honor to :Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, 1 Billy Graham Parkway, Charlotte, North Carolina, 28201-0001 or Good Shepherd Hospice, 3470 Lakeland Hills Blvd., Lakeland, Florida, 33805 / chaptershealth.org/locations/Lakeland-resource-center-good-shepherd-hospice-administrative-office/

We welcome you to leave your condolences, thoughts, and memories of Emory on our Tribute Wall.

Mowell Funeral Home & Cremation Service, Fayetteville, www.mowells.com

To send flowers to the family or plant a tree in memory of Homer, please visit our floral store.

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook

March 7, 1924 - March 24, 2024

Pause Video

Share Obituary:

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook 31062708

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook

Obituary & Events

Tribute Wall

7 Trees, Flowers, or Condolences have been sent in support of Homer's family - View on Tribute Wall

7 New Posts

Share a memory

Type here to share a memory of Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook or send condolences to the family…

Photos/Video

Candle

Mementos

Post Now

Homer Emory "Em" Holbrook Obituary

H. Emory “Em” Holbrook, 100, of Lakeland, Florida passed away Sunday, March 24, 2024. He was born to Alfred S. Holbrook, Sr. and Bessie Bagwell Holbrook in Cherokee County, Georgia on Friday, March 7, 1924.

Em is preceded in death by his parents; wife of 54 years, Dorothy Livingston Holbrook; daughter, Sandra, 4 adult brothers, 2 adult sisters and 4 infant sisters. He is survived by his son and daughter-in-law, Jere and Beverly Holbrook; granddaughter, Lori and Richard Wilkins; grandson, Jason and Amy Holbrook; great granddaughters, Taylor (Jake) Green, Makinsy Wendel, Delaney Wilkins, Kendall Holbrook, Lauren Holbrook, and Peyton Holbrook; 2 sisters-in-law, numerous nieces, nephews, and their children.

Em served his country during W.W. II in the United States Army. He was a participant in the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. He was shot a few weeks later near St. Lo France. Emory was awarded the Purple Heart for his injury. He worked for Delta Air Lines in Atlanta as an airline jet engine mechanic for 28 years before retiring.

Funeral service will be held Monday, April 1, 2024, in the Chapel of Mowell Funeral Home, Fayetteville at 2:00 PM with Pastor John Christopher officiating. Visitation will occur prior to the service from 1:00 to 2:00 PM at the funeral home. Em will be laid to rest at Westminster Memorial Gardens in Peachtree City.

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made in Emory’s honor to :Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, 1 Billy Graham Parkway, Charlotte, North Carolina, 28201-0001 or Good Shepherd Hospice, 3470 Lakeland Hills Blvd., Lakeland, Florida, 33805 / chaptershealth.org/locations/Lakeland-resource-center-good-shepherd-hospice-administrative-office/

We welcome you to leave your condolences, thoughts, and memories of Emory on our Tribute Wall.

Mowell Funeral Home & Cremation Service, Fayetteville, www.mowells.com

To send flowers to the family or plant a tree in memory of Homer, please visit our floral store.

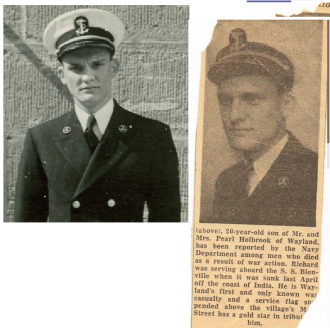

Richard Homer Holbrook 1922 - 1942 New York - India

Richard Homer Holbrook

Born: January 9, 1922

Hometown: Wayland, NY

Class: 1943

Service: Merchant Marine

Position / Rank: Engine Cadet

Date / Place of death: April 11, 1942 / Berhampur,

India

Date / Place of burial: April 12, 1942 / Catholic

Cemetery, Berhampur, India

Age: 20

Richard H. Holbrook signed on as Engine Cadet aboard the SS Bienville at the Port of

New York on December 12, 1941, less than a week after the United States officially

entered World War II. He was joined by his Academy classmate, Cadet-Midshipman

Robert W. Corliss who signed on as Deck Cadet. According to Corliss’ report, the

Bienville sailed from New York on December 15, 1941 with a crew of 43 bound for Suez

and other ports in the Middle East as directed. After discharging its cargo the Bienville

was ordered to Calcutta, India to load a cargo of manganese ore, jute, burlap and

general cargo. The ship sailed from Calcutta on April 3, bound for Columbo, Ceylon.

Unfortunately, the ship was also bound for a collision with six Japanese aircraft carriers,

escorted by cruisers and destroyers, that were conducting a raid into the Bay of Bengal

known by the Japanese Navy as “Operation C”.

During the morning 4 to 8 watch on April 6, 1942 Cadet-Midshipman Robert Corliss was

a lookout on the bridge when he heard gunfire ahead. In light of the situation he was

ordered to wake all hands. At 0718 the Bienville was attacked by Japanese aircraft and

was hit at the Number 2 hatch, starting a fire. While the crew was fighting the fire two

more Japanese aircraft attacked the Bienville, but without hitting the ship. At this early

point in the war the Bienville had no defensive armament.

In the growing light the crew of the Bienville saw a Japanese aircraft carrier, later

identified as the IJNS Ryujo, and its escorting cruisers and destroyers. The captain

attempted to run from the Japanese fleet and lay a smoke screen to hide behind.

However, their efforts were in vain. At about 0740 a Japanese cruiser, identified after

the war as the heavy cruiser IJNS Chokai, opened fire from less than two miles away,

hitting the ship at least five times, severely wounding Richard Holbrook.

Richard Homer Holbrook

Born: January 9, 1922

Hometown: Wayland, NY

Class: 1943

Service: Merchant Marine

Position / Rank: Engine Cadet

Date / Place of death: April 11, 1942 / Berhampur,

India

Date / Place of burial: April 12, 1942 / Catholic

Cemetery, Berhampur, India

Age: 20

Richard H. Holbrook signed on as Engine Cadet aboard the SS Bienville at the Port of

New York on December 12, 1941, less than a week after the United States officially

entered World War II. He was joined by his Academy classmate, Cadet-Midshipman

Robert W. Corliss who signed on as Deck Cadet. According to Corliss’ report, the

Bienville sailed from New York on December 15, 1941 with a crew of 43 bound for Suez

and other ports in the Middle East as directed. After discharging its cargo the Bienville

was ordered to Calcutta, India to load a cargo of manganese ore, jute, burlap and

general cargo. The ship sailed from Calcutta on April 3, bound for Columbo, Ceylon.

Unfortunately, the ship was also bound for a collision with six Japanese aircraft carriers,

escorted by cruisers and destroyers, that were conducting a raid into the Bay of Bengal

known by the Japanese Navy as “Operation C”.

During the morning 4 to 8 watch on April 6, 1942 Cadet-Midshipman Robert Corliss was

a lookout on the bridge when he heard gunfire ahead. In light of the situation he was

ordered to wake all hands. At 0718 the Bienville was attacked by Japanese aircraft and

was hit at the Number 2 hatch, starting a fire. While the crew was fighting the fire two

more Japanese aircraft attacked the Bienville, but without hitting the ship. At this early

point in the war the Bienville had no defensive armament.

In the growing light the crew of the Bienville saw a Japanese aircraft carrier, later

identified as the IJNS Ryujo, and its escorting cruisers and destroyers. The captain

attempted to run from the Japanese fleet and lay a smoke screen to hide behind.

However, their efforts were in vain. At about 0740 a Japanese cruiser, identified after

the war as the heavy cruiser IJNS Chokai, opened fire from less than two miles away,

hitting the ship at least five times, severely wounding Richard Holbrook.

Wayland Bradford Holbrook (Rev.)- Clinton, TN - Belle Fourche, SD

Rev. Wayland Holbrook

November 17, 1935 — April 16, 2022

View Funeral Webcast

Rev. Wayland B. Holbrook, age 86 of Belle Fourche, died Saturday, April 16, 2022 at the Rolling Hills Healthcare Center in Belle Fourche.

The funeral service will be held 10:30am Friday, April 22, 2022 at Leverington Funeral Home of the Northern Hills in Belle Fourche, with Pastor Andy Anderson officiating. Visitation will be held one hour prior to the service. Interment will take place in Pine Slope Cemetery.

Wayland’s funeral will be broadcasted live from his obituary page, located on the funeral home’s website: www.LeveringtonFH.com.

In lieu of flowers, memorials are suggested to the building fund at Emmanuel Baptist Church of Belle Fourche.

Wayland Bradford Holbrook was born on November 17, 1935, in Clinton, Tennessee to Ralph and Ruth (Bradford) Holbrook. Wayland graduated from Harrison Chilhowee Baptist Academy in 1954. He received a BA from Belmont College in 1959. Wayland attended New Orleans Seminary for 1 ½ years. He attended Luther Rice Seminary and received his Master of Divinity in 1979 and Doctor of Ministry in 1980.

Wayland married Marilyn Field on June 17, 1977. Wayland and Marilyn enjoyed a life of ministry serving the Lord together.

Rev. Holbrook was ordained a Baptist Minister in 1956 and spent more than 50 years in Pioneer Mission work. He has served in Tennessee, Louisiana, New Mexico, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, Wyoming, and since 1984 in South Dakota. His last position he had the privilege of serving was for 8 years in pastoral ministries. He had the joy of encouraging, ministering to, and serving other pastors in the Black Hills Area Baptist Association.

Wayland is survived by his wife, Marilyn of Spearfish; three children, Sherry, Ralph, and Mary; two brothers, Joe (Pam) and Jerry (Carole) of Tennessee; stepson, Brad Field of Broadus, MT; stepdaughter Sheila (Crickett) O’Day of MO; several grandchildren and great grandchildren.

He was preceded in death by his parents and brother Jack.

Funeral Service

10:30 A.M. – Friday – April 22, 2022

Leverington Funeral Home

of the Northern Hills

Belle Fourche, South Dakota

Rev. Wayland Holbrook

November 17, 1935 — April 16, 2022

View Funeral Webcast

Rev. Wayland B. Holbrook, age 86 of Belle Fourche, died Saturday, April 16, 2022 at the Rolling Hills Healthcare Center in Belle Fourche.

The funeral service will be held 10:30am Friday, April 22, 2022 at Leverington Funeral Home of the Northern Hills in Belle Fourche, with Pastor Andy Anderson officiating. Visitation will be held one hour prior to the service. Interment will take place in Pine Slope Cemetery.

Wayland’s funeral will be broadcasted live from his obituary page, located on the funeral home’s website: www.LeveringtonFH.com.

In lieu of flowers, memorials are suggested to the building fund at Emmanuel Baptist Church of Belle Fourche.

Wayland Bradford Holbrook was born on November 17, 1935, in Clinton, Tennessee to Ralph and Ruth (Bradford) Holbrook. Wayland graduated from Harrison Chilhowee Baptist Academy in 1954. He received a BA from Belmont College in 1959. Wayland attended New Orleans Seminary for 1 ½ years. He attended Luther Rice Seminary and received his Master of Divinity in 1979 and Doctor of Ministry in 1980.

Wayland married Marilyn Field on June 17, 1977. Wayland and Marilyn enjoyed a life of ministry serving the Lord together.

Rev. Holbrook was ordained a Baptist Minister in 1956 and spent more than 50 years in Pioneer Mission work. He has served in Tennessee, Louisiana, New Mexico, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, Wyoming, and since 1984 in South Dakota. His last position he had the privilege of serving was for 8 years in pastoral ministries. He had the joy of encouraging, ministering to, and serving other pastors in the Black Hills Area Baptist Association.

Wayland is survived by his wife, Marilyn of Spearfish; three children, Sherry, Ralph, and Mary; two brothers, Joe (Pam) and Jerry (Carole) of Tennessee; stepson, Brad Field of Broadus, MT; stepdaughter Sheila (Crickett) O’Day of MO; several grandchildren and great grandchildren.

He was preceded in death by his parents and brother Jack.

Funeral Service

10:30 A.M. – Friday – April 22, 2022

Leverington Funeral Home

of the Northern Hills

Belle Fourche, South Dakota

Jack Holbrook 1933 - 2016 Carter, KY - Flatwood, KY

Jack Holbrook, 83, of Flatwoods, passed away Tuesday morning at his home.

Mr. Holbrook was born Feb. 3, 1933, at Denton in Carter County, the son of the late Millard and Maude Holbrook. He was also preceded in death by two brothers, J.T. and Clinton Holbrook, and a sister, Joyce Brock.

Mr. Holbrook was a staff sergeant/cook in the U.S. Air Force, stationed in Guam, from 1950 to 1953. He was a retired tractor driver in the shipping department at AK Steel. He was a founding and longtime former member of 13th Street Baptist Church in Ashland. He grew delicious heirloom tomatoes, cooked big Kentucky breakfasts when family visited, closely followed the stock market and was generous with his time and money. He enjoyed spending time with his grandsons. As an Ashland Tomcats supporter, Papaw Jack rarely missed a practice or event when two of his grandsons were on football and wrestling teams. He was the spiritual leader of multiple generations, always eager to teach a biblical lesson.

Surviving are his wife, Beulah Burton Holbrook, whom he married April 4, 1953; two sons, Blake (Pam) Holbook of Ashland and Vincent (Susan) Holbrook of Kernersville, N.C.; a daughter, Ronda (Floyd) Taylor of Nicholasville; four grandsons, Dr. Ian (Catherine) Holbrook of Winston-Salem, N.C., Evan Holbrook of Ashland and Jack and William Holbrook of Kernersville; a great grandson, Jackson, expected in April; two brothers, Bill (Joyce) Holbrook of Russell and Charles (Jewel) Holbrook of Chesnee, S.C.; four sisters, Ruth (the late Gardner) Lykins of Ben Salem, Pa., Gladys (the late Ersel) Shelton of Ashland, Kathleen (the late Gaylord) Price of Westwood and Janet (Larry) Zeger of Tucson, Ariz.; and several nieces and nephews and their families.

The funeral will be at 1 p.m. Friday, Feb. 12, 2016, at Steen Funeral Home-Central Avenue Chapel in Ashland by Pastor Henry Montgomery. Burial will be in Bellefonte Memorial Gardens in Flatwoods.

Friends may call after 11 a.m. Friday at the funeral home.

Contributions are suggested to Putnam Stadium, c/o Donna Suttle, 1520 Lexington Avenue, Ashland, KY 41101.

Romans 8:38-39 and Revelation 21:1-5

Condolences may be sent to steenfuneralhome.com

Jack Holbrook, 83, of Flatwoods, passed away Tuesday morning at his home.

Mr. Holbrook was born Feb. 3, 1933, at Denton in Carter County, the son of the late Millard and Maude Holbrook. He was also preceded in death by two brothers, J.T. and Clinton Holbrook, and a sister, Joyce Brock.

Mr. Holbrook was a staff sergeant/cook in the U.S. Air Force, stationed in Guam, from 1950 to 1953. He was a retired tractor driver in the shipping department at AK Steel. He was a founding and longtime former member of 13th Street Baptist Church in Ashland. He grew delicious heirloom tomatoes, cooked big Kentucky breakfasts when family visited, closely followed the stock market and was generous with his time and money. He enjoyed spending time with his grandsons. As an Ashland Tomcats supporter, Papaw Jack rarely missed a practice or event when two of his grandsons were on football and wrestling teams. He was the spiritual leader of multiple generations, always eager to teach a biblical lesson.

Surviving are his wife, Beulah Burton Holbrook, whom he married April 4, 1953; two sons, Blake (Pam) Holbook of Ashland and Vincent (Susan) Holbrook of Kernersville, N.C.; a daughter, Ronda (Floyd) Taylor of Nicholasville; four grandsons, Dr. Ian (Catherine) Holbrook of Winston-Salem, N.C., Evan Holbrook of Ashland and Jack and William Holbrook of Kernersville; a great grandson, Jackson, expected in April; two brothers, Bill (Joyce) Holbrook of Russell and Charles (Jewel) Holbrook of Chesnee, S.C.; four sisters, Ruth (the late Gardner) Lykins of Ben Salem, Pa., Gladys (the late Ersel) Shelton of Ashland, Kathleen (the late Gaylord) Price of Westwood and Janet (Larry) Zeger of Tucson, Ariz.; and several nieces and nephews and their families.

The funeral will be at 1 p.m. Friday, Feb. 12, 2016, at Steen Funeral Home-Central Avenue Chapel in Ashland by Pastor Henry Montgomery. Burial will be in Bellefonte Memorial Gardens in Flatwoods.

Friends may call after 11 a.m. Friday at the funeral home.

Contributions are suggested to Putnam Stadium, c/o Donna Suttle, 1520 Lexington Avenue, Ashland, KY 41101.

Romans 8:38-39 and Revelation 21:1-5

Condolences may be sent to steenfuneralhome.com

John Page Holbrook - Davie, NC - Davidson, KY

Lexington

|

View Obituaries

John Page Holbrook

January 24, 1936 - March 28, 2024

Send Flowers

Send Sympathy Card

Plant Trees

In Loving Memory

John Page Holbrook

January 24, 1936 - March 28, 2024

John Page Holbrook

Send Flowers

Send Flowers

Order Flowers for the Family

Send Sympathy Card

Send Card

Show Your Sympathy to the Family

Plant Trees

Plant Trees

In Remembrance

John's Obituary

John Page Holbrook, 88, of Linwood, passed away March 25, 2024, at Davidson Rehab of Lexington, after being in declining health.

A celebration of his life will be held at 11:00 am Tuesday, April 2, 2024, at the Davidson Funeral Home Chapel, with the Rev. Tommy Hepler officiating the service, burial will follow in the Lakeview Baptist Church Cemetery. The family will receive friends Monday night from 6:00pm to 8:00pm at the funeral home.

John was born January 24, 1936, in Davie County, to Archie Clay Holbrook and Bonnie Marie Poplin Pinnix. John was of the Baptist faith, having retired from Burlington Industry. His passion was family and especially his grandchildren and great grandchildren. He was a loving father, grandfather, brother, who will be missed by all. In addition to his parents, he is preceded in death by his wife, Effie Faye Holbrook, daughter, Donna Faye Cooper, son, Conley Edgar Holbrook, sisters, Mary Smith, Maria Long, Virginia Combs, Tottie Holloman.

Left to cherish his memories, are his sons, Randy Page and wife Renay of Linwood, Archie Glenn Holbrook and wife Margaret of Lexington, daughters, Bonnie Sue Ingram and husband Donnie of Salisbury, 13 grandchildren and 41 great grandchildren, also brother, Roger Dale Pinnix and wife Pam of Spencer.

In lieu of flowers, memorials may be made to: Hospice of Davidson County, 200 Hospice Way, Lexington, NC, 27292.

Lexington

|

View Obituaries

John Page Holbrook

January 24, 1936 - March 28, 2024

Send Flowers

Send Sympathy Card

Plant Trees

In Loving Memory

John Page Holbrook

January 24, 1936 - March 28, 2024

John Page Holbrook

Send Flowers

Send Flowers

Order Flowers for the Family

Send Sympathy Card

Send Card

Show Your Sympathy to the Family

Plant Trees

Plant Trees

In Remembrance

John's Obituary

John Page Holbrook, 88, of Linwood, passed away March 25, 2024, at Davidson Rehab of Lexington, after being in declining health.

A celebration of his life will be held at 11:00 am Tuesday, April 2, 2024, at the Davidson Funeral Home Chapel, with the Rev. Tommy Hepler officiating the service, burial will follow in the Lakeview Baptist Church Cemetery. The family will receive friends Monday night from 6:00pm to 8:00pm at the funeral home.

John was born January 24, 1936, in Davie County, to Archie Clay Holbrook and Bonnie Marie Poplin Pinnix. John was of the Baptist faith, having retired from Burlington Industry. His passion was family and especially his grandchildren and great grandchildren. He was a loving father, grandfather, brother, who will be missed by all. In addition to his parents, he is preceded in death by his wife, Effie Faye Holbrook, daughter, Donna Faye Cooper, son, Conley Edgar Holbrook, sisters, Mary Smith, Maria Long, Virginia Combs, Tottie Holloman.

Left to cherish his memories, are his sons, Randy Page and wife Renay of Linwood, Archie Glenn Holbrook and wife Margaret of Lexington, daughters, Bonnie Sue Ingram and husband Donnie of Salisbury, 13 grandchildren and 41 great grandchildren, also brother, Roger Dale Pinnix and wife Pam of Spencer.

In lieu of flowers, memorials may be made to: Hospice of Davidson County, 200 Hospice Way, Lexington, NC, 27292.

Virgil Holbrook - 1931 - 2014 - Newport, RI

Virgil Holbrook

1931 - 2014

Recommend Virgil's obituary to your friends

Obituary

Tribute Wall

Photos

Obituary of Virgil Holbrook

Please share a memory of Virgil to include in a keepsake book for family and friends.

View Tribute Book

Virgil Holbrook, age 82, of Morning View, passed away Monday, March 17, 2014 at Baptist Convalescent Center in Newport. He was a retired Chemical Operator for Hilton Davis (for 44 years), a member and deacon at Hickory Grove Baptist Church in Independence, and a U.S. Army and National Guard Veteran. Virgil enjoyed traveling, gardening, four wheeling, bicycling, reading (especially history), and spending time with his grandchildren. He is survived by his wife, Elizabeth Mullins Holbrook; sons, Douglas E. (Margie) Holbrook and Elliott (Gina) Holbrook; sisters, Jalie Williams, Estelle Hall, and Krean Gross; brothers, H.B. Holbrook and Charlie Holbrook; grandchildren, Benjamin Holbrook, Angel Fiszlewicz, Madison K. Holbrook, Keaton E. Holbrook, Corey Nicholas Holbrook, and Mallory N. Holbrook; and great-granddaughter, Emily Mae Holbrook.

Visitation will be Saturday, March 22, 2014 from 9 a.m. to 11 a.m. with funeral services immediately following at 11 a.m. at Hickory Grove Baptist Church, 11969 Taylor Mill Rd., Independence, KY 41051.

Interment will be at Independence Cemetery. Chambers and Grubbs Funeral Home in Independence will be assisting the family.

Memorials may be made to Northern Kentucky Easter Seals Center, 212 Levassor Ave., Covington, KY 41014 or the Disabled American Veterans, 3494 Dust Commander Dr., Hamilton, OH 45011 To send flowers to the family or plant a tree in memory of Virgil Holbrook, please visit Tribute Store

Virgil Holbrook

1931 - 2014

Recommend Virgil's obituary to your friends

Obituary

Tribute Wall

Photos

Obituary of Virgil Holbrook

Please share a memory of Virgil to include in a keepsake book for family and friends.

View Tribute Book

Virgil Holbrook, age 82, of Morning View, passed away Monday, March 17, 2014 at Baptist Convalescent Center in Newport. He was a retired Chemical Operator for Hilton Davis (for 44 years), a member and deacon at Hickory Grove Baptist Church in Independence, and a U.S. Army and National Guard Veteran. Virgil enjoyed traveling, gardening, four wheeling, bicycling, reading (especially history), and spending time with his grandchildren. He is survived by his wife, Elizabeth Mullins Holbrook; sons, Douglas E. (Margie) Holbrook and Elliott (Gina) Holbrook; sisters, Jalie Williams, Estelle Hall, and Krean Gross; brothers, H.B. Holbrook and Charlie Holbrook; grandchildren, Benjamin Holbrook, Angel Fiszlewicz, Madison K. Holbrook, Keaton E. Holbrook, Corey Nicholas Holbrook, and Mallory N. Holbrook; and great-granddaughter, Emily Mae Holbrook.

Visitation will be Saturday, March 22, 2014 from 9 a.m. to 11 a.m. with funeral services immediately following at 11 a.m. at Hickory Grove Baptist Church, 11969 Taylor Mill Rd., Independence, KY 41051.

Interment will be at Independence Cemetery. Chambers and Grubbs Funeral Home in Independence will be assisting the family.

Memorials may be made to Northern Kentucky Easter Seals Center, 212 Levassor Ave., Covington, KY 41014 or the Disabled American Veterans, 3494 Dust Commander Dr., Hamilton, OH 45011 To send flowers to the family or plant a tree in memory of Virgil Holbrook, please visit Tribute Store