Joe DiMaggio, Yankee Clipper, Dies at 84. By Joseph Durso. March 9, 1999.

Joe DiMaggio, the flawless center fielder for the New York Yankees who, along with Babe Ruth and Mickey Mantle, symbolized the team's dynastic success across the 20th century and whose 56-game hitting streak in 1941 made him an instant and indelible American folk hero, died early today at his home here. He was 84 years old.

DiMaggio died shortly after midnight, nearly five months after undergoing surgery for cancer of the lungs.

He had spent 99 days in the hospital while battling lung infections and pneumonia, and his illness generated a national vigil as he was reported near death several times. He went home on Jan. 19, alert but weak and with little hope of surviving.

Several family members and close friends were at his bedside this morning.

DiMaggio's body was flown to Northern California for a funeral Thursday and for burial in San Francisco, his hometown.

In a country that has idolized and even immortalized its 20th century heroes, from Charles A. Lindbergh to Elvis Presley, no one more embodied the American dream of fame and fortune or created a more enduring legend than Joe DiMaggio.

He became a figure of unequaled romance and integrity in the national mind because of his consistent professionalism on the baseball field, his marriage to the Hollywood star Marilyn Monroe, his devotion to her after her death, and the pride and courtliness with which he carried himself throughout his life.

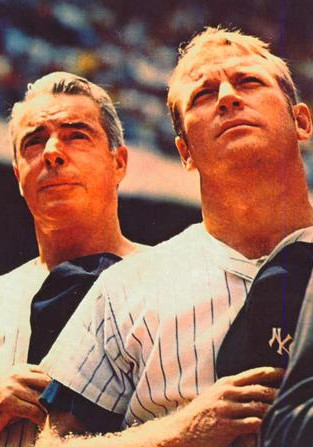

DiMaggio burst onto the baseball scene from San Francisco in the 1930's and grew into the game's most gallant and graceful center fielder. He wore No. 5 and became the successor to Babe Ruth (No. 3) and Lou Gehrig (No. 4) in the Yankees' pantheon. DiMaggio was the team's superstar for 13 seasons, beginning in 1936 and ending in 1951, and appeared in 11 All-Star Games and 10 World Series. He was, as the writer Roy Blount Jr. once observed, ''the class of the Yankees in times when the Yankees outclassed everybody else.''

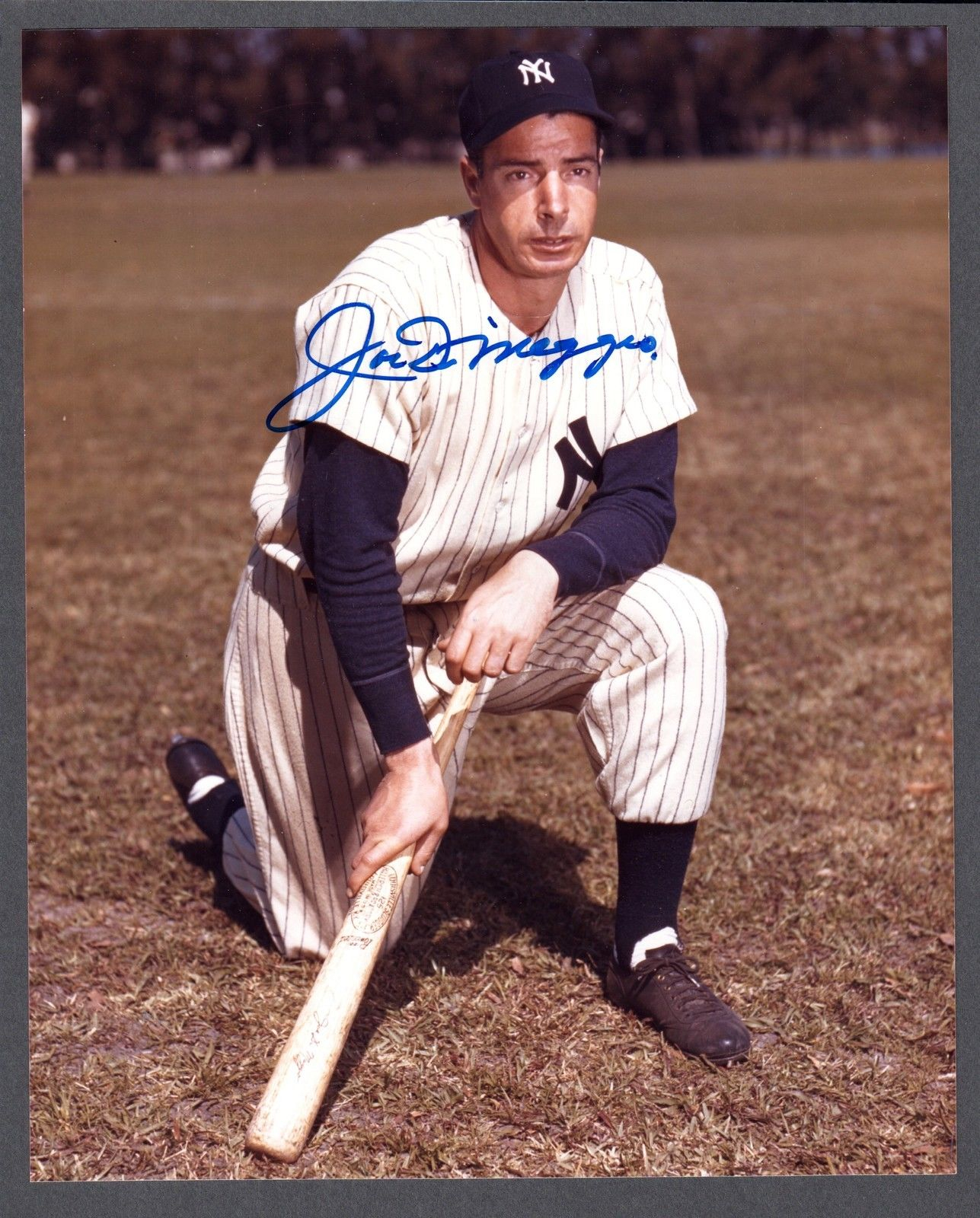

He was called the Yankee Clipper and was acclaimed at baseball's centennial in 1969 as ''the greatest living ballplayer,'' the man who in 1,736 games with the Yankees had a career batting average of .325 and hit 361 home runs while striking out only 369 times, one of baseball's most amazing statistics. (By way of comparison, Mickey Mantle had 536 homers and struck out 1,710 times; Reggie Jackson slugged 563 homers and struck out 2,597 times.)

But DiMaggio's game was so complete and elegant that it transcended statistics; as The New York Times said in an editorial when he retired, ''The combination of proficiency and exquisite grace which Joe DiMaggio brought to the art of playing center field was something no baseball averages can measure and that must be seen to be believed and appreciated.''

DiMaggio glided across the vast expanse of center field at Yankee Stadium with such incomparable grace that long after he stopped playing, the memory of him in full stride remains evergreen. He disdained theatrical flourishes and exaggerated moves, never climbing walls to make catches and rarely diving headlong. He got to the ball just as it fell into his glove, making the catch seem inevitable, almost preordained. The writer Wilfrid Sheed wrote, ''In dreams I can still see him gliding after fly balls as if he were skimming the surface of the moon.''

His batting stance was as graceful as his outfield stride. He stood flat-footed at the plate with his feet spread well apart, his bat held still just off his right shoulder. When he swung, his left, or front, foot moved only slightly forward. His swing was pure and flowing with an incredible follow-through. Casey Stengel, the Yankee manager for DiMaggio's last three seasons, said, ''He made the rest of them look like plumbers.''

At his peak, he was serenaded as ''Joltin' Joe DiMaggio'' by Les Brown and saluted as ''the great DiMaggio'' by Ernest Hemingway in ''The Old Man and the Sea.'' He was mentioned in dozens of films and Broadway shows; the sailors in ''South Pacific'' sing that Bloody Mary's skin is ''tender as DiMaggio's glove.'' Years later, he was remembered by Paul Simon, who wondered with everybody else: ''Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio? A nation turns its lonely eyes to you.''

Sensitive to anything written, spoken or sung about him, he confessed that he was puzzled by Simon's lyrics and sought an answer when he met Simon in a restaurant in New York. ''I asked Paul what the song meant, whether it was derogatory,'' DiMaggio recalled. ''He explained it to me.''

When injuries eroded his skills and he could no longer perform to his own standard, he turned his back on his $100,000 salary -- he and his rival Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox then drew the largest paychecks in sports -- and retired in 1951 with the dignity that remained his hallmark.

His stormy marriage to Marilyn Monroe lasted less than a year, but they remained one of America's ultimate romantic fantasies: the tall, dark and handsome baseball hero wooing and winning the woman who epitomized Hollywood beauty, glamour and sexuality.

He was private and remote. Even Monroe, at their divorce proceedings, said he was given to black moods and would tell her, ''Leave me alone.'' He once said, with disdain, that he kept track of all the books written about his storied life without his consent, and by the late 1990's knew that the count had passed 33.

Yet he could be proud, reclusive and vain in such a composed, almost studied way that his reclusiveness contributed to his mystique. In the book ''Summer of '49,'' David Halberstam wrote that DiMaggio ''guards his special status carefully, wary of doing anything that might tarnish his special reputation. He tends to avoid all those who might define him in some way other than the way he defined himself on the field.''

Quietly Doing It All For 13 Seasons

DiMaggio joined the Yankees in 1936, missed three years while he served in the Army Air Forces in World War II, then returned and played through the 1951 season, when Mickey Mantle arrived to open yet another era in the remarkable run of Yankee success. In his 13 seasons, DiMaggio went to bat 6,821 times, got 2,214 hits, knocked in 1,537 runs, amassed 3,948 total bases and reached base just under 40 percent of the time.

For decades, baseball fans argued over who was the better pure hitter, DiMaggio or Williams. Long after both had retired, Williams said: ''In my heart, I always felt I was a better hitter than Joe. But I have to say, he was the greatest baseball player of our time. He could do it all.''

And he did it all with a sureness and coolness that seemed to imply an utter lack of emotion. DiMaggio was once asked why he did not vent his frustrations on the field by kicking a bag or tossing a bat. The outfielder, who chain-smoked cigarettes and had suffered from ulcers, replied: ''I can't. It wouldn't look right.''

But he betrayed his sensitivity in a memorable gesture of annoyance in the sixth game of the 1947 World Series after his long drive was run down and caught in front of the 415-foot sign in left-center field at Yankee Stadium by Al Gionfriddo of the Brooklyn Dodgers. As DiMaggio rounded first base, he saw Gionfriddo make the catch and, with his head down, kicked the dirt.

The angry gesture was so shocking that it made headlines.

In the field, DiMaggio ran down long drives with a gliding stride and deep range. In 1947, he tied what was then the American League fielding record for outfielders by making only one error in 141 games.

He also had one of the most powerful and precise throwing arms in the business and was credited with 153 assists in his 13 seasons.

His longtime manager, Joe McCarthy, once touched on another DiMaggio skill. ''He was the best base runner I ever saw,'' McCarthy said. ''He could have stolen 50, 60 bases a year if I let him. He wasn't the fastest man alive. He just knew how to run bases better than anybody.''

Three times DiMaggio was voted his league's most valuable player: in 1939, 1941 and 1947. In 1941, the magical season of his 56-game hitting streak, he won the award even though Williams batted .406.

In each of his first four seasons with the Yankees, DiMaggio played in the World Series, and the Yankees won all four. He appeared in the Series 10 times in 13 seasons over all, and nine times the Yankees won. And although he failed to get enough votes to make the baseball Hall of Fame when he became eligible in 1953, perhaps because his aloofness had alienated some of the writers who did the voting, he sailed into Cooperstown two years later.

Whitey Ford was a rookie pitcher in 1950 when he first saw DiMaggio, and he later remembered, ''I just stared at the man for about a week.''

Baseball Blood In a Fisherman's Family

Joseph Paul DiMaggio was born on Nov. 25, 1914, in Martinez, Calif., a small fishing village 25 miles northeast of the Golden Gate. He was the fourth son and the eighth of nine children born to Giuseppe Paolo and Rosalie DiMaggio, who had immigrated to America in 1898 from Sicily. His father was a fisherman who moved his family to North Beach, the heavily Italian section near the San Francisco waterfront, the year Joe was born.

The two oldest sons, Tom and Michael, joined their father as fishermen; Michael later fell off a boat and drowned. But the three other sons became major league outfielders by way of the sandlots of San Francisco. Vince, four years older than Joe, played 10 seasons with five teams and led the National League in strikeouts six times. Dominic, three years younger than Joe, was known as the Little Professor because he wore eyeglasses when he played 11 seasons with the Boston Red Sox, hitting .298 for his career. Of the three, Joe was the natural.

He started as a shortstop in the Boys Club League when he was 14, dropped out of Galileo High School after one year and joined Vince on the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League, the highest level of minor league baseball. It was 1932, and Joe was still 17 years old.

The next year, in his first full season with the Seals, he hit .340 with 28 home runs and knocked in 169 runs in 187 games. He also hit safely in 61 games in a row, eight years before he made history in the big leagues by hitting in 56. He tore up the league during the next two seasons, hitting .341 and .398. But he injured his left knee stepping out of a cab while hurrying to dinner at his sister's house after a Sunday doubleheader and was considered damaged goods by most of the teams in the big leagues.

He got his chance at the majors because two scouts, Joe Devine and Bill Essick, persisted in recommending him to the Yankees. The general manager, Ed Barrow, talked it over with his colleagues. And for $25,000 plus five players, the Yankees bought him from the Seals.

DiMaggio was left in San Francisco for the 1935 season to heal his knee and put the finishing touches on his game, then was brought up to New York in 1936 to join a talented team that included Lou Gehrig, Bill Dickey, Tony Lazzeri, Red Rolfe, Red Ruffing and Lefty Gomez. It was two years after Babe Ruth had left, and an era of success had ended.

But now, the rookie from California was arriving with a contract for $8,500, and a new era was beginning. It was delayed because of a foot injury, but DiMaggio made his debut on May 3 against the St. Louis Browns. He went on to play 138 games, got 206 hits with 29 home runs, batted .323 and drove in 125 runs. In the fall, the Yankees made the first of four straight trips to the World Series -- they would go on to play in 22 out of 29 Series through 1964 -- and the rookie hit .346 against the Giants and made a spectacular catch in deepest center field in the Polo Grounds before a marveling crowd of 43,543, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

DiMaggio's luster was sometimes dimmed by salary disputes. In 1937 he hit .346 with 46 home runs and 167 r.b.i. and the following year he held out for $40,000, but was forced to sign for $25,000. DiMaggio's holdout lasted a couple of weeks into the season; when he returned, he was booed. When he began the 1941 season, he had missed four of his first five openers because of injury or salary fights, and many fans resented it. ''He got hurt early in his career, more than he ever let on,'' Phil Rizzuto once said.

He also had to endure the casual bigotry that existed when he first came up. Life magazine, in a 1939 article intending to compliment him, said: ''Although he learned Italian first, Joe, now 24, speaks English without an accent, and is otherwise well adapted to most U.S. mores. Instead of olive oil or smelly bear grease he keeps his hair slick with water. He never reeks of garlic and prefers chicken chow mein to spaghetti.''

But he energized the fans by leading the league in hitting in 1939 (at .381) and again in 1940 (.352). Then in 1941, he put together what has since been known simply as the Streak, and fashioned perhaps the most enduring record in sports. Streaks were nothing new to DiMaggio. He had hit in those 61 straight games for the Seals, in 18 straight as a rookie with the Yankees, in 22 straight the next year and in 23 straight the year after that. In fact, in 1941, he hit safely in the last 19 games in spring training, and he kept hitting for eight more games after the regular season opened.

The Streak began on May 15, 1941, with a single in four times at bat against the Chicago White Sox. The next day, he hit a triple and a home run. Two weeks later, he had a swollen neck but still hit three singles and a home run in Washington. The next week against the St. Louis Browns, he went 3 for 5 in one game, then 4 for 8 in a doubleheader the next day with a double and three home runs. His streak stood at 24.

On June 17, he broke the Yankees' club record of 29 games. On June 26, he was hitless with two out in the eighth inning against the Browns, but he doubled, and his streak reached 38. On June 29, in a doubleheader against Washington, DiMaggio lined a double in the first game to tie George Sisler's modern major league record of hitting in 41 straight games and then broke Sisler's record in the second game by lining a single. On July 1, with a clean single against the Red Sox at Yankee Stadium, he matched Willie Keeler's major league record of 44 games, set in 1897 when foul balls did not count as strikes. The next day he broke it with a three-run homer.

As DiMaggio kept hitting safely, radio announcers kept an excited America informed, Bojangles Robinson danced on the Yankee dugout roof at the Stadium for good luck, and Les Brown recorded ''Joltin' Joe DiMaggio . . . we want you on our side.''

The Streak Ends, But Not the Heroics

The Streak finally ended on the steamy night of July 17 in Cleveland, before 67,468 fans at Municipal Stadium. The Cleveland pitchers were Al Smith and Jim Bagby Jr., but the stopper was the Indians' third baseman, Ken Keltner, who made two dazzling backhand plays deep behind third base to rob DiMaggio of hits. It is sometimes overlooked that DiMaggio was intentionally walked in the fourth inning of that game, and that he promptly started a 16-game streak the next day.

In 56 games, DiMaggio had gone to bat 223 times and delivered 91 hits for a .408 average, including 15 home runs. He drew 21 walks, twice was hit by pitched balls, scored 56 runs and knocked in 55. He hit in every game for two months, and struck out just seven times.

The Yankees, fourth in the American League when the streak began, were six games in front when it ended, and won the pennant by 17.

DiMaggio was passing milestones in his personal life, too. In 1939, he married an actress, Dorothy Arnold. In October 1941, his only child, Joseph Jr., was born. In addition to his son, he is survived by his brother Dominic; two granddaughters, Paula and Cathy; and four great-grandchildren.

On Dec. 3, 1942, DiMaggio enlisted in the Army Air Forces and spent the next three years teaching baseball in the service. Along with other baseball stars like Bob Feller and Williams, he resumed his career as soon as the war ended, returning to the Yankees for the 1946 season and a year later leading them back into the World Series.

His most dramatic moments came in the season of 1949, after he was sidelined by bone spurs on his right heel and did not play until June 26. Then he flew to Boston to join the team in Fenway Park, hit a single and home run the first two times he went to bat, hit two more home runs the next day and another the day after that.

The Yankees entered the final two days of that season trailing the Red Sox by one game. They had to sweep two games in Yankee Stadium to win the pennant, and they did. There were poignant moments before the first game when 69,551 fans rocked the stadium and cheered their hero, who was being honored with a Joe DiMaggio Day. He was almost too weak to play because of a severe viral infection, but he did, and he hit a single and double before removing himself from center field on wobbly legs.

After the Yankees won yet another World Series in 1951, he retired and eased into a second career as Joe DiMaggio, legend. It included cameo roles as a broadcaster, a spring training instructor with the Yankees and a coach with the Oakland Athletics, appearances at old-timers' games, where he was invariably the last player introduced, and a larger role, with surprising impact, as a mellow and credible pitchman on television commercials.

He had long since created an image of a loner both on and off the playing field, particularly in the 1930's and 1940's when he lived in hotels in Manhattan and was considered something of a man about town. He once was characterized by a teammate as the man ''who led the league in room service.'' But he spent many evenings at Toots Shor's restaurant in Manhattan, where he hid out at a private table far in the back while Shor protected him from his public.

But his legend took a storybook turn in 1952, the year after he retired from the Yankees, when DiMaggio, whose marriage to Dorothy Arnold had ended in divorce in 1944, arranged a dinner date with Marilyn Monroe in California. They were married in San Francisco on Jan. 14, 1954, and spent nine months trying to reconcile their differences before they divorced in October. DiMaggio always seemed tortured by Monroe's sex goddess image. He protested loudly during the making of Billy Wilder's ''The Seven Year Itch'' when the script called for her to cool herself over a subway grate while a sudden wind blew her skirt up high.

But when the actress seemed on the verge of an emotional collapse in 1961, DiMaggio took her to the Yankees' training camp in Florida for rest and support. And when she died of an overdose of barbiturates at age 36 on Aug. 4, 1962, he took charge of her funeral, and for the next 20 years he sent roses three times a week to her crypt in the Westwood section of Los Angeles.

Finally at Ease In the Spotlight

When DiMaggio made an unexpected and dramatic return to the public scene in the 1970's as a television spokesman for the Bowery Savings Bank of New York and for Mr. Coffee, a manufacturer of coffee makers, he did it with remarkable ease for a man who had been obsessed with privacy, who had once confided that he always had ''a knot'' in his stomach because he was so shy and tense.

Gone was the stage fright that had rattled him during earlier sorties into broadcasting. Instead, he was the epitome of credibility, the graying and trustworthy hero who had hit his home runs and was now returning to extol the virtues of saving money and brewing coffee. He soon became a familiar and comforting presence for a generation of baseball fans who never saw him play.

For some years, he lived in San Francisco with his widowed sister Marie in a house in the Marina District that he had bought for his parents in 1939 and that he and his sister had shared with Marilyn Monroe. When the damp San Francisco climate troubled the arthritis in his back, he began to spend most of his time in Florida, where he established his home. He played golf and made selected excursions to Europe and the Far East, where the demand for his appearance and his autograph returned high dividends.

But he seemed to take the most pleasure in establishing a children's wing, called the Joe DiMaggio Children's Hospital, at Memorial Regional Hospital in Hollywood, Fla. And he seemed to relish the invitations back to Yankee Stadium, where he frequently threw out the first ball on opening day, tall but slightly stooped, dressed elegantly, as always, in a dark business suit, walking to the mound and lobbing one to the catcher.

It was there on the day the season ended last year, as the Yankees set a team record with their 114th victory, that he was acclaimed on yet another Joe DiMaggio Day, the timeless hero and the symbol of Yankee excellence, acknowledging the cheers of Yankee players and fans.

It was the kind of cheering that accompanied him through life and that he had quietly come to expect. It recalled the time when he and Monroe, soon after their wedding, took a trip to Tokyo. She continued on to entertain American troops in Korea, and said with fascination when she returned, ''Joe, you've never heard such cheering.''

And Joe DiMaggio replied softly, ''Yes, I have.''

ADVERTISEMENT

BY

Looking for more information?

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson  Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson

Amanda S. Stevenson