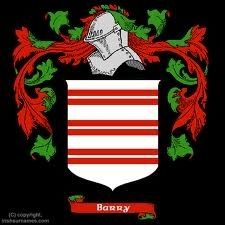

Barry Family History & Genealogy

Barry Last Name History & Origin

AddHistory

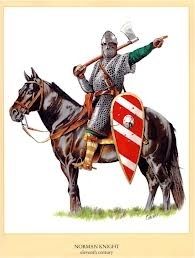

The Barry family (Irish: de Barra) is a family of Cambro-Norman origins which once had extensive land holdings in Wales and County Cork,Ireland. The founder of the family was a Norman knight, Odo de Barri who assisted in the Norman Conquest during the 11th century. As reward for his military services, Odo was granted estates in Pembrokeshire and around Barry, including Barry Island just off the coast and named after the 6th century Saint Baruc.

Odo’de Barri grandson, Gerald of Wales, a 12th century scholar, gives the origin of his family's name, de Barry, in his Itinerarium Cambriae (1191): "Not far from Caerdyf is a small island situated near the shore of the Severn, called Barri, from St. Baroc … . From hence a noble family, of the maritime parts of South Wales, who owned this island and the adjoining estates, received the name of de Barri."

Many family members later assisted in the Norman invasion of Ireland. For the family's services, King John of England awarded Philip's son, William de Barry, extensive baronies in the Kingdom of South Munster, specifically the defunct Uí Liatháin kingdom (O'Lethan and Imokilly) with its late seat at Castlelyons.

Odo de Barry was the grantee of the immense manor of Manorbierin Pembrokeshire, which included the manors of Jameston and Manorbier Newton, as well as the manors of Begelly and Penally. He built the first motte-and-bailey at Manorbier. His son, William FitzOdo de Barry, is the common ancestor of the Barry family in Ireland. He rebuilt Manorbier Castle in stone and the family retained the lordship of Manorbier until the 15th century.

Issue of William FitzOdo de Barry

He had sons: Robert, Philip, Walter and Gerald (better known as Giraldus Cambrensis) by Angharad (also known as Hangharad) daughter of Gerald de Windsor (died 1135) andNest ferch Rhys (died after 1136). After Gerald's death, Nest's sons married her to Stephen, her husband's constable of Cardigan Castle, by whom she had another two sons; the eldest was Robert Fitz-Stephen.

Robert de Barry accompanied his half-uncle Robert Fitz-Stephen in the Norman invasion of Ireland. He took part in the Siege of Wexford and was killed at the battle of Lismore in 1185.

Philip de Barry came to Ireland in 1185 to assist his half-uncle Robert Fitz-Stephen, and his first cousin Raymond FitzGerald (also known as Raymond Le Gros), in their efforts to recover lands in the modern county Cork - the cantreds of Killede, Olethan and Muscarydonegan.

The latter cantred, variously called Muscry-donnegan or "O'Donegan's country" or "Múscraighe Tri Maighe", was a rural deanery in the Diocese of Cloyne.[1] It is now identified as the barony of Orrery and Kilmore.[2] The name "Olethan" (or "Oliehan") is an anglicisation of the Gaelic Uí Liatháin which refers to the early medieval kingdom of the Uí Liatháin. Thispetty kingdom encompassed most of the present Barony of Barrymore and the neighbouring barony of Kinnatalloon. The name Killyde survives in "Killeady Hills", the name of the hill country south of the city of Cork.[3][4] These cantreds or baronies had been expropriated by another (half) first cousin, Ralph Fitz-Stephen (died 1182), the grandson of Nesta by Stephen, Constable of Cardigan. Robert Fitz-Stephen eventually ceded these territories to Philip de Barry, his half-nephew. On 24 February 1206, King John I of England confirmedWilliam de Barry, Philip's son, in the possession of these territories and, by letters patent, conferred on him the Lordships of Castlelyons, Buttevant and Barry's Court in East Cork[1]. The family would eventually acquire the honours of Viscount Buttevant and Earl of Barrymore.

Barryscourt Castle near Carrigtwohill was the seat of the Barry family from the 12th century until 1617 when they removed to Barrymore Castle in Castlelyons. In 1771, the 7th Earl saw Barrymore Castle burn to the ground.[5] The family fortunes were subsequently dissipatated by his issue, the 7th and 8th Earls.

The name of the town of Buttevant is believed to derive from the family's battle cry - Boutez-en-Avant, roughly translating as "Kick your way through".

Name Origin

Gerald of Wales, a 12th century scholar, gives the origin of his family's name, de Barry, in his Itinerarium Cambriae (1191): "Not far from Caerdyf is a small island situated near the shore of the Severn, called Barri, from St. Baroc … . From hence a noble family, of the maritime parts of South Wales, who owned this island and the adjoining estates, received the name of de Barri."

Spellings & Pronunciations

Barry,Di Barri,De Barri,Di Barre,Barrymore

Nationality & Ethnicity

The Barry family (Irish: de Barra) is a family of Cambro-Norman origins (Normandy,France) which once had extensive land holdings in Wales and County Cork,Ireland. The founder of the family was a Norman knight, Odo, who assisted in the Norman Conquest during the 11th century. As reward for his military services, Odo was granted estates in Pembrokeshire and around Barry, including Barry Island just off the coast and named after the 6th century Saint Baruc.

The Barry surname comes from de Barri, a French Norman name which may have been derived from a small village in Normandy known as La Barre. family of Cambro-Norman origins (Normandy,France) which once had extensive land holdings in Wales and County Cork,Ireland. The founder of the family was a Norman knight, Odo, who assisted in the Norman Conquest during the 11th century. As reward for his military services, Odo was granted estates in Pembrokeshire and around Barry, including Barry Island just off the coast and named after the 6th century Saint Baruc.

Famous People named Barry

A. Constantine Barry (1815–88), American educator and politician

Alfred Barry (1826–1910), Anglican Bishop of Sidney; second son of Charles Barry

Ann Street Barry (1734–1801), English actress; second wife of Spranger Barry

Bonny Barry (born 1960), Australian politician

Brent Barry (born 1971), American sports commentator and former basketball player; third son of Rick Barry

Brian Barry (1936–2009), British philosopher

Cathy Barry (born 1967), English pornographic actress

Charles Barry (1795–1860), English architect, main designer of the Palace of Westminster

Charles Barry, Jr. (1823–1900), English architect; eldest son of Charles Barry

Christopher Barry (born 1925), British television director

Claudja Barry (born 1952), Jamaican-Canadian singer and actress

B. Constance Barry

Damion Barry (born 1982), Trinidadian sprinter

Daniel Barry (disambiguation)

Dave Barry (born 1947), American author and columnist, winner of the Pulitzer Prize

David Barry (disambiguation)

David de Barry, 5th Viscount Barry (c. 1550–1617), Irish peer

Dede Barry (born 1972), American cyclist

Denis Barry (1929–2003), president of the United States Chess Federation (1993–96)

Don "Red" Barry (1912–80), American film actor

Drew Barry (born 1973), American retired basketball player; fourth son of Rick Barry

Edward Middleton Barry (1830–80), English architect; third son of Charles Barry

Elizabeth Barry (1658–1713), English actress

Fred Barry (born 1948), American football player in the National Football League

Frederick G. Barry (1845–1909), member of the U.S. House of Representatives

Gareth Barry (born 1981), English footballer

Garret Barry (disambiguation)

Gene Barry (1919–2009), American stage, screen and television actor

Gerald Barry (disambiguation)

Glenn Barry, American musician, former bass player in the symphonic metal band Kamelot

Grant Barry, American musician

Hilary Barry (born 1969), New Zealand television personality

Jack Barry (disambiguation)

James Barry (disambiguation)

James de Barry, 4th Viscount Buttevant (1520–81), Irish peer

Jason Barry-Smith (born 1969), Australian operatic baritone, vocal coach, composer and arranger

Jeff Barry (born 1938), American pop music songwriter, singer and record producer

J. Esmonde Barry (1923–2007), Canadian healthcare activist and political commentator

Joan Barry (disambiguation)

John Barry (disambiguation)

John Wolfe-Barry (1836–1918), English civil engineer, co-designer of Tower Bridge; youngest son of Charles Barry

Jonathan Barry (born 1988), Bahamian cricketer

Jonathan B. Barry (born 1945), American Democratic politician, businessman, and farmer

Jon Barry (born 1969), American television analyst and former basketball player; second son of Rick Barry

Kate Barry (1752–1823), heroine of the American Revolutionary War

Keith Barry (born 1976), Irish illusionist, mentalist and close-up magician

Kevin Barry (1902–20), Irish Republican Army member

Kevin Barry (boxer) (born 1959), New Zealand former boxer, boxing trainer and manager

Krystal Barry, American beauty queen

Len Barry

Leo Barry

Lyall Barry, New Zealand swimmer

Lynda Barry

Lynn Barry

Madame du Barry

Mamadou Barry, Guinean footballer

Margaret Stuart Barry

Marion Barry

Marty Barry

Mary Barry, Canadian musician

Maryanne Trump Barry

Max Barry

Michael Barry (disambiguation)

Morris Barry

Patrick Barry (disambiguation)

Paul Barry

Peter Barry

Philip Barry

Rahmane Barry

Ralph Andrews Barry (1883–1939), philatelic writer

Raymond J. Barry

Redmond Barry

Rick Barry

Robert L. Barry

Rod Barry

Sam Barry

Scooter Barry

Sebastian Barry

Spranger Barry

Stuart Milner-Barry

Susan R. Barry

Sy Barry

Todd Barry

Tom Barry

Tom Barry (screenwriter)

Wesley Barry

William Barry (disambiguation)

Early Barries

These are the earliest records we have of the Barry family.

Barry Family Members

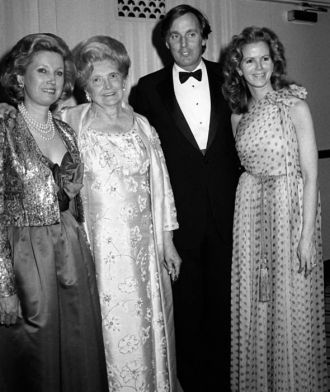

Barry Family Photos

Discover Barry family photos shared by the community. These photos contain people and places related to the Barry last name.

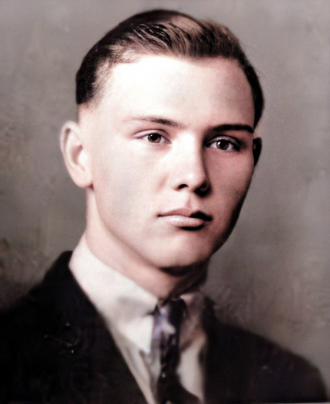

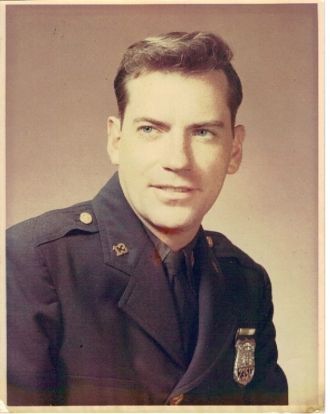

Mick Barry was the grandson of Sir Redmond Barry, I've been told.

People in photo include: Mick Barry

People in photo include: Merlyn Thacher, Frank Dreistadt, Francis Gavin, Mary Navikas, Harriet Fisher, Irene Jones, Stanley Bittenbender, Horace Shiffer, Howard Spray, Frank Uzdella, John Hrehach, Johanna Nichols, Loretta Barry, Samuel Apfelbaum, Lawrence Carr, James O'Hara, Edward S. Zoransky , James O'Hara, and Joseph Stone

People in photo include: Samuel Apfelbaura, Merlyn Thacher, Frank Dreistadt, Francis Gavin, Mary Navikas, Harriet Fisher, Irene Jones, Stanley Bittenbender, Horace Shiffer, Howard Spray, Frank Uzdella, John Hrehach, Johanna Nichols, Loretta Barry, Samuel Apfelbaum, Lawrence Carr, James Edwards, Joseph Zoransky, James O'Hara, Joseph Stone, Frederick Rickert, and Cyril McHalc

People in photo include: Tom Barry

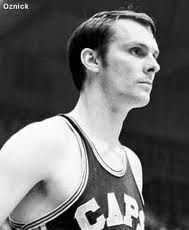

Height: 6-7; Weight: 220 lbs.

Honors: Elected to Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame (1987); NBA champion (1975); NBA Finals MVP (1975); All-NBA First Team (1966, '67, '74, '75, '76); All-NBA Second Team (1973); Rookie of the Year (1966); Eight-time NBA All-Star; All-Star MVP (1967); One of 50 Greatest Players in NBA History (1996).

ABA Honors: ABA champion (1969); All-ABA First Team (1969, '70, '71, '72); Four-time ABA All-Star.

Full Name: Richard Francis Dennis Barry III

Born: 3/28/44 in Elizabeth, N.J.

High School: Roselle Park (N.J.)

College: Miami (Fla.)

Drafted: San Francisco Warriors, 1965 (No. 2 overall)

Transactions: Signed with Oakland Oaks of ABA, 1967; Oaks become Washington Capitols, 1969; Traded to New York Nets, 1970; Returned to NBA's Warriors, '72; Signed with Houston Rockets, 6/17/78

In 1915, during World War I, he enlisted in the Royal Field Artillery at Cork and became a soldier in the British Army.

“ In June, in my seventeenth year, I had decided to see what this Great War was like. I cannot plead I went on the advice of John Redmond or any other politician, that if we fought for the British we would secure Home Rule for Ireland, nor can I say I understood what Home Rule meant. I was not influenced by the lurid appeal to fight to save Belgium or small nations. I knew nothing about nations, large or small. I went to the war for no other reason than that I wanted to see what war was like, to get a gun, to see new countries and to feel a grown man. Above all I went because I knew no Irish history and had no national consciousness.[3] ”

He fought in Mesopotamia (then part of the Ottoman Empire, present day Iraq). He rose to the rank of sergeant.[4] Barry was offered a commission in the Royal Munster Fusiliers but refused it.[citation needed] While outside Kut-el-Amara Barry first heard of the Easter Rising.

On his return to Cork he was involved with ex-servicemen's organisations. In 1920, Barry joined the 3rd (West) Cork Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) which was then engaged in the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921). He was involved in brigade council meetings, was brigade-training officer, flying column commander, was consulted by IRA General Headquarters Staff (GHQ), and also participated in the formation of the IRA First Southern Division. The West Cork Brigade became famous for its discipline, efficiency and bravery, and Barry garnered a reputation as the most brilliant field commander of the war.

On 28 November 1920, Barry's unit ambushed and killed almost a whole platoon of British Auxiliaries at Kilmichael, County Cork. In March 1921 at Crossbarry in the same county, Barry and 104 men, divided into seven sections, broke out of an encirclement of 1,200 strong British force from the Essex Regiment. In total, the British Army stationed over 12,500 troops in County Cork during the conflict, while Barry's men numbered no more than 310. Eventually, Barry's tactics made West Cork ungovernable for the British authorities.

"They said I was ruthless, daring, savage, blood thirsty, even heartless. The clergy called me and my comrades murderers; but the British were met with their own weapons. They had gone in the mire to destroy us and our nation and down after them we had to go."[5]

The son of a stationer, Barry was articled to a firm of surveyors and architects until 1817, when he set out on a three-year tour of France, Greece, Italy, Egypt, Turkey, and Palestine to study architecture. In 1820 he settled in London. One of his first works was the Church of Saint Peter at Brighton, which he began in the 1820s. In 1832 he completed the Travellers’ Club in Pall Mall, the first work in the style of an Italian Renaissance palace to be built in London. In the same style and on a grander scale he built (1837–41) the Reform Club. He was also engaged on numerous private mansions in London, the finest being Bridgewater House, which was completed in the 1850s. In Birmingham one of his best works, King Edward’s School, was built in the Perpendicular Gothic style between 1833 and 1837. For Manchester he designed the Royal Institution of Fine Arts (1824–35) and the Athenaeum (1836–39), and for Halifax the town hall (completed in the early 1860s).

In 1835 a design competition was held for a new Houses of Parliament building, also called Westminster Palace, to replace the one destroyed by fire in 1834. Barry won the contest in 1836, and the project occupied him for the rest of his life. With the help of Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, Barry designed a composition ornamented in the Gothic Revival style and featuring two asymmetrically placed towers. The complex of the Houses of Parliament (1837–60) is Barry’s masterpiece.

Barry was elected an associate of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1840 and a royal academician in the following year and received many foreign honours. He was knighted in 1852 and, on his death, was buried in Westminster Abbey.

His son, Edward Middleton Barry (1830–80), also a noted architect, completed the work on the Houses of Parliament.

These are some of the architectual accomplishments of Charles Barry:

The Palace of Westminster, also known as the Houses of Parliament

Clock Tower, Palace of Westminster also known as "Big Ben"

10 Kensington Palace Gardens

Andaz Liverpool Street Hotel

Bridgewater House, Westminster

Church of All Saints

Dunrobin Castle

Halifax Town Hall

Lancaster House

Nelson's Column

Pepper Pot, Brighton

Reform Club

Royal Manchester Institution

St Andrew's Church, Waterloo Street, Hove

St Saviour's Church, Ringley

Travellers Club

Upper Brook Street Chapel, Manchester

Victoria Tower

Ancestry

Nesta

Robert's role in the invasion and colonisation of Ireland, and his position in the medieval Welsh-Irish Norman society, was largely due to his membership of the extended family of descendants of Princess Nest ferch Rhys of Deheubarth.[1] Nest had three sons and a daughter with her husband Gerald de Windsor: the daughter, Angharad, married William de Barry. Nest also had a son - Robert Fitz-Stephen - by her second husband.

William de Barry

William Fitz Odo de Barry was the son of Odo or Otho, a Norman knight who assisted in the Norman Conquest of England and Wales during the 11th century. William rebuilt Manorbier Castle in stone and the family retained the lordship of Manorbier until the 15th century.

Barry's brothers were Philip de Barry, Edmond de Barry and Gerald of Wales. He accompanied his half-uncle Robert to Ireland in 1169 and took part in the Siege of Wexford,[2] where he was wounded. He is mentioned as still engaged in warfare about 1175 by his brother Gerald, the historian, who highly extols his prowess.

According to the "Archdall's Lodge" (1789) source, Robert, "after his services in Ireland is said to seat himself at Sevington, in Kent," and "about the year 1185 being killed at Lismore,". But as he was elder than his brother Gerald, who was born in 1146 or 1147, this Robert was about forty years old in 1185. The same source reports that the Robert who was slain near Lismore in that year was only an adolescens that is, between fifteen and twenty eight years of age. It is improbable therefore that Robert (aged 40) was slain at Lismore. That person is more likely to be his namesake, the son of his brother Philip

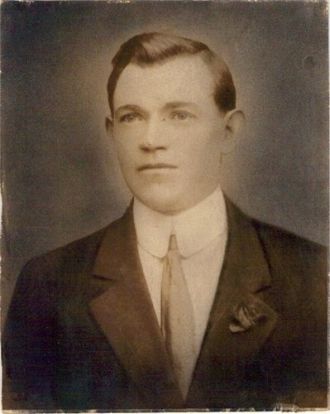

People in photo include: Robert De Barry

On 18 October 1171, Henry II landed a much bigger army in Waterford to ensure his continuing control over the preceding Norman force. In the process he took Dublin and had accepted the fealty of the Irish kings and bishops by 1172, so creating the Lordship of Ireland, which formed part of his Angevin Empire.

Treaty of Windsor

Pope Adrian IV, the only English pope, in one of his earliest acts issued a papal bull in 1155, giving Henry authority to invade Ireland as a means of ensuring reform by bringing the Irish Church more directly under the control of the Holy See.[1] Little contemporary use, however, was made of the bull Laudabiliter since its text enforced papal suzerainty not only over the island of Ireland but of all islands off of the European coast, including England, in virtue of the Constantinian Donation. The relevant text reads:

There is indeed no doubt, as thy Highness doth also acknowledge, that Ireland and all other islands which Christ the Son of Righteousness has illumined, and which have received the doctrines of the Christian faith, belong to the jurisdiction of St. Peter and of the holy Roman Church.

References to Laudabiliter become more frequent in the later Tudor period when the researches of the Renaissance humanist scholars cast doubt on the historicity of the Donation. But even if the Donation was spurious, other documents such as Dictatus papae (1075–87) reveal that by the 12th century the Papacy felt it had political powers superior to all kings and local rulers.

Pope Alexander III, who was Pope at the time of the invasion, mentioned and reconfirmed the effect of Laudabiliter in his "Privilege" of 1172.

Invasion of 1169

Original landing site for the invasion –

Bannow Bay

After losing the protection of Tyrone Chief, Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, High King of Ireland, who died in 1166, MacMorrough was forcibly exiled by a confederation of Irish forces under the new High King, Rory O'Connor. MacMurrough fled first to Bristol and then to Normandy. He sought and obtained permission from Henry II of England to use the latter's subjects to regain his kingdom. Having received an oath of fealty from Dermod, Henry gave him letters patent in the following words:

Henry, King of England, duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, and earl of Anjou, to all his liegemen, English, Norman, Welsh and Scotch, and to all the nations under his dominion, greeting. When these letters shall come into your hands, know ye, that we have received Dermod, Prince of Leinster, into the bosom of our grace and benevolence. Wherefore, whosoever, in the ample extent of all our territories, shall be willing to assist in restoring that prince, as our vassal and liegeman, let such person know, that we do hereby grant to him our licence and favour for the said undertaking.[2]

By 1167 MacMurrough had obtained the services of Maurice Fitz Gerald and later persuaded Rhys ap Gruffydd Prince of Deheubarth to release Fitz Gerald's half-brother Robert Fitz-Stephen from captivity to take part in the expedition. Most importantly he obtained the support of the Earl of Pembroke Richard de Clare, known as Strongbow.

The first Norman knight to land in Ireland was Richard fitz Godbert de Roche in 1167, but it was not until 1169 that the main body of Norman, Welsh and Flemish forces landed in Wexford. Within a short time Leinster was conquered, Waterford and Dublin were under Diarmait's control. Strongbow married Diarmait's daughter, Aoife, and was named as heir to the Kingdom of Leinster. This latter development caused consternation to Henry II, who feared the establishment of a rival Norman state in Ireland. Accordingly, he resolved to visit Leinster to establish his authority.

Arrival of Henry II in 1171

Henry landed with a large fleet at Waterford in 1171, becoming the first King of England to set foot on Irish soil. Both Waterford and Dublin were proclaimed Royal Cities. In November Henry accepted the submission of the Irish kings in Dublin. In 1172 Henry arranged for the Irish bishops to attend the Synod of Cashel and to run the Irish Church in the same manner as the Church in England. Adrian's successor, Pope Alexander III, then ratified the grant of Ireland to Henry, ".. following in the footsteps of the late venerable Pope Adrian, and in expectation also of seeing the fruits of our own earnest wishes on this head, ratify and confirm the permission of the said Pope granted you in reference to the dominion of the kingdom of Ireland."

Henry was happily acknowledged by most of the Irish Kings, who saw in him a chance to curb the expansion of both Leinster and the Normans. He then had to leave for England to deal with papal legates investigating the death of Thomas Becket in 1170, and then for France to suppress the Revolt of 1173–1174. His next involvement with Ireland was the Treaty of Windsor in 1175 with Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair.[3]

However, with both Diarmuid and Strongbow dead (in 1171 and 1176 respectively) and Henry back in England, within two years this treaty was not worth the vellum it was inscribed upon. John de Courcy invaded and gained much of east Ulster in 1177, Raymond FitzGerald (known as Raymond le Gros) had already captured Limerick and much of the Kingdom of Thomond (also known as North Munster), while the other Norman families such as Prendergast, fitz-Stephen, fitz-Gerald, fitz-Henry and le Poer were actively carving out petty kingdoms for themselves.

In 1185 Henry awarded his Irish territories to his 18-year-old youngest son, John, with the title Dominus Hiberniae ("Lord of Ireland"), and planned to establish it as a kingdom for him. When John unexpectedly succeeded his brother Richard as king in 1199, the Lordship became a possession of the English Crown.

Subsequent assaults

While the main Norman invasion concentrated on Leinster, with submissions made to Henry by the other provincial kings, the situation on the ground outside Leinster remained unchanged. However, individual groups of knights invaded:

Connacht in 1175 and 1200–03, led by William de Burgh

Munster in 1177, led by Raymond le Gros

East Ulster in 1177, led by John de Courcy

These further conquests were not planned by or made with royal approval, but were then incorporated into the Lordship under Henry's control, as with Strongbow's initial invasion

People in photo include: Philip De Barry

On 18 October 1171, Henry II landed a much bigger army in Waterford to ensure his continuing control over the preceding Norman force. In the process he took Dublin and had accepted the fealty of the Irish kings and bishops by 1172, so creating the Lordship of Ireland, which formed part of his Angevin Empire.

Background

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Laudabiliter

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Privilege of Pope Alexander III to Henry II

Treaty of Windsor

Pope Adrian IV, the only English pope, in one of his earliest acts issued a papal bull in 1155, giving Henry authority to invade Ireland as a means of ensuring reform by bringing the Irish Church more directly under the control of the Holy See.[1] Little contemporary use, however, was made of the bull Laudabiliter since its text enforced papal suzerainty not only over the island of Ireland but of all islands off of the European coast, including England, in virtue of the Constantinian Donation. The relevant text reads:

There is indeed no doubt, as thy Highness doth also acknowledge, that Ireland and all other islands which Christ the Son of Righteousness has illumined, and which have received the doctrines of the Christian faith, belong to the jurisdiction of St. Peter and of the holy Roman Church.

References to Laudabiliter become more frequent in the later Tudor period when the researches of the Renaissance humanist scholars cast doubt on the historicity of the Donation. But even if the Donation was spurious, other documents such as Dictatus papae (1075–87) reveal that by the 12th century the Papacy felt it had political powers superior to all kings and local rulers.

Pope Alexander III, who was Pope at the time of the invasion, mentioned and reconfirmed the effect of Laudabiliter in his "Privilege" of 1172.

Invasion of 1169

Original landing site for the invasion –

Bannow Bay

After losing the protection of Tyrone Chief, Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, High King of Ireland, who died in 1166, MacMorrough was forcibly exiled by a confederation of Irish forces under the new High King, Rory O'Connor. MacMurrough fled first to Bristol and then to Normandy. He sought and obtained permission from Henry II of England to use the latter's subjects to regain his kingdom. Having received an oath of fealty from Dermod, Henry gave him letters patent in the following words:

Henry, King of England, duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, and earl of Anjou, to all his liegemen, English, Norman, Welsh and Scotch, and to all the nations under his dominion, greeting. When these letters shall come into your hands, know ye, that we have received Dermod, Prince of Leinster, into the bosom of our grace and benevolence. Wherefore, whosoever, in the ample extent of all our territories, shall be willing to assist in restoring that prince, as our vassal and liegeman, let such person know, that we do hereby grant to him our licence and favour for the said undertaking.[2]

By 1167 MacMurrough had obtained the services of Maurice Fitz Gerald and later persuaded Rhys ap Gruffydd Prince of Deheubarth to release Fitz Gerald's half-brother Robert Fitz-Stephen from captivity to take part in the expedition. Most importantly he obtained the support of the Earl of Pembroke Richard de Clare, known as Strongbow.

The first Norman knight to land in Ireland was Richard fitz Godbert de Roche in 1167, but it was not until 1169 that the main body of Norman, Welsh and Flemish forces landed in Wexford. Within a short time Leinster was conquered, Waterford and Dublin were under Diarmait's control. Strongbow married Diarmait's daughter, Aoife, and was named as heir to the Kingdom of Leinster. This latter development caused consternation to Henry II, who feared the establishment of a rival Norman state in Ireland. Accordingly, he resolved to visit Leinster to establish his authority.

Arrival of Henry II in 1171

Henry landed with a large fleet at Waterford in 1171, becoming the first King of England to set foot on Irish soil. Both Waterford and Dublin were proclaimed Royal Cities. In November Henry accepted the submission of the Irish kings in Dublin. In 1172 Henry arranged for the Irish bishops to attend the Synod of Cashel and to run the Irish Church in the same manner as the Church in England. Adrian's successor, Pope Alexander III, then ratified the grant of Ireland to Henry, ".. following in the footsteps of the late venerable Pope Adrian, and in expectation also of seeing the fruits of our own earnest wishes on this head, ratify and confirm the permission of the said Pope granted you in reference to the dominion of the kingdom of Ireland."

Henry was happily acknowledged by most of the Irish Kings, who saw in him a chance to curb the expansion of both Leinster and the Normans. He then had to leave for England to deal with papal legates investigating the death of Thomas Becket in 1170, and then for France to suppress the Revolt of 1173–1174. His next involvement with Ireland was the Treaty of Windsor in 1175 with Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair.[3]

However, with both Diarmuid and Strongbow dead (in 1171 and 1176 respectively) and Henry back in England, within two years this treaty was not worth the vellum it was inscribed upon. John de Courcy invaded and gained much of east Ulster in 1177, Raymond FitzGerald (known as Raymond le Gros) had already captured Limerick and much of the Kingdom of Thomond (also known as North Munster), while the other Norman families such as Prendergast, fitz-Stephen, fitz-Gerald, fitz-Henry and le Poer were actively carving out petty kingdoms for themselves.

In 1185 Henry awarded his Irish territories to his 18-year-old youngest son, John, with the title Dominus Hiberniae ("Lord of Ireland"), and planned to establish it as a kingdom for him. When John unexpectedly succeeded his brother Richard as king in 1199, the Lordship became a possession of the English Crown.

Subsequent assaults

While the main Norman invasion concentrated on Leinster, with submissions made to Henry by the other provincial kings, the situation on the ground outside Leinster remained unchanged. However, individual groups of knights invaded:

Connacht in 1175 and 1200–03, led by William de Burgh

Munster in 1177, led by Raymond le Gros

East Ulster in 1177, led by John de Courcy

These further conquests were not planned by or made with royal approval, but were then incorporated into the Lordship under Henry's control, as with Strongbow's initial invasion

Barry Family Tree

Discover the most common names, oldest records and life expectancy of people with the last name Barry.

Updated Barry Biographies

Popular Barry Biographies

Barry Death Records & Life Expectancy

The average age of a Barry family member is 74.0 years old according to our database of 17,813 people with the last name Barry that have a birth and death date listed.

Life Expectancy

Oldest Barries

These are the longest-lived members of the Barry family on AncientFaces.

Other Barry Records

Share memories about your Barry family

Leave comments and ask questions related to the Barry family.

My father maried in Canada (after having moved with his family to manchester, NH) - and then moved to NJ in the 1930s, where he raised his 6 sons. He died in NJ in 1988 at the age of 85.

William Barry

William Barry Thankyou

William Barry

I was hoping to locate a census, either US or NY State, of the 1860s or 1870s of the Essex County area. I know my great grandfather settled in Willsboro, New York. According to my great aunt, her father (my great grandfather) landed in Canada from Ireland in the 1850s then came to the US and settled in Essex County, New York. I am not sure when exactly, but I'm sure he was settled there by the 1870s and probably earlier. I think a good place to locate him would be the census because the census should list his country and city of origin as well as his parent's names, at least his father. My great aunt was born in 1876 in Essex County, NY, but was a child of my great grandfather's second marriage, his first wife having died in child birth. There were five surviving children from his first marriage and five surviving children from his second, my aunt being one of them from the second marriage.

Followers & Sources